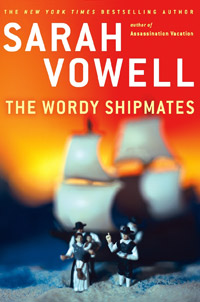

Sarah Vowell’s New Book, The Wordy Shipmates

NPR Darling Digs Up America's Literary Root

Early on in her fifth and latest book, The Wordy Shipmates, public radio personality and New York Times op-ed columnist Sarah Vowell writes, “The United States is often called a Puritan nation. Well, here is one way in which it emphatically is not: Puritan lives were overwhelmingly, fanatically literary.” It’s one of many assertions that amount to nothing less than a sassy, rollicking revisionist history of the pilgrims, and the legacy they left us. Contrary to popular belief, Vowell claims, today’s Evangelical Christians have little in common with bookish English scholars like John Winthrop who settled the Massachusetts Bay in the 17th century. As Vowell fans might suspect, her argument is cogent, impassioned, and highly readable-and it’s also laugh-out-loud funny.

Vowell spoke to me about the book last week over the phone from Manhattan.

I hear the events of 9/11 inspired you to write The Wordy Shipmates. Well, there’s this sermon of Winthrop’s, The Model of Christian Charity, where he talks to his fellow about-to-be New Englanders about “the city on a hill.” It’s basically a sermon about community, and about how they’re going to have to take care of each other. My favorite part is when he tells them, “We should rejoice and mourn and suffer together as members of the same body.” I kept thinking about that, living in Manhattan. September 11th was the worst thing that had ever happened to any of us. So I found comfort in Winthrop at that time.

But really the moment I started writing the book was at Reagan’s funeral when Sandra Day O’Connor was reading Winthrop’s sermon because of Reagan’s association with the “city on a hill” phrase. It just seemed so ironic-that a man who was all about cutting social programs and slashing the Housing and Urban Development budget to the extent that homelessness more or less was invented in his administration-that he was associated with this phrase from Winthrop’s sermon about charity and generosity. So the impetus for the book wasn’t just this rosy little feeling of togetherness; it was also a kind of snarky mission to reclaim that sermon.

You’re an atheist, but you’re drawn to the writings of people with strong religious beliefs. What’s your relationship with religion? I’m definitely a moralistic atheist. I had a very religious upbringing until I was a teenager. Working on this book, I realized that like a lot of working-class kids throughout the history of world, my entry into the world of ideas and scholarship and reading and study came through religion. In the little town in Oklahoma I lived in until I was 11, hardly anyone had gone to college. It was a country music town; it was the least academic place you could imagine. But at church three or four times a week, there was this outlet. It was like an ongoing book club where it was just one book, but it was all about study and interpretation and memorization and just worshipping this text. So even though it was a real Holy Roller fundamentalist kind of church, it really did have a scholarly component that opened up my whole life.

How have we misinterpreted the Puritanism of America’s founders? The one thing that gets remembered from Winthrop’s sermon is this image of America as a city upon a hill, and that’s how Ronald Reagan bandied it about-the idea that we are a beacon of hope, end of story. Winthrop’s sermon is much more grey. He sees the colonists’ mission as having two possible outcomes: It could be a beacon of hope, or it could fail. That’s why Reagan adopting the city on a hill as his pet sound bite is so American. He just wanted to focus on the optimistic aspect of that image, and not the idea that when you’re up there that high, everyone can watch you mess up. The early New Englanders were terrified of failing their God. Somehow we inherited the idea of ourselves as a beacon of hope for others to look up to, but lost the sense of responsibility that comes with that. Fear of failure is good. Blind optimist isn’t the best mindset.

You talk about American exceptionalism. Are you an American exceptionalist? I know it’s stupid-especially for me, not believing in God-to believe we are a country chosen by God, but it’s incredibly difficult to get away from it. Of course, in some ways, this country is unlike any place on Earth, but the idea that we are the best is stupid and silly and frequently not based in fact, but it’s so much a part of our cultural DNA that it takes every ounce of my cognizant self to realize how ridiculous that is.

4•1•1

Sarah Vowell will speak and take questions at UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Sunday, March 1, at 7 p.m. For tickets, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.