Stopping Suicide, Averting Violence

Glendon Association Hosts Free Annual Suicide and Violence Prevention Forum

Violence against one’s self and others is a problem throughout the world, and Santa Barbara is no exception. In hopes of stagnating these threats of suicide and alleviating the need for gang violence, the Glendon Association hosts its annual Suicide and Violence Prevention Forum this coming Wednesday, October 7, in Santa Maria and again on Thursday, October 8, at the Marjorie Luke Theatre in Santa Barbara. On tap are a number of esteemed speakers, and three of them share their stories below.

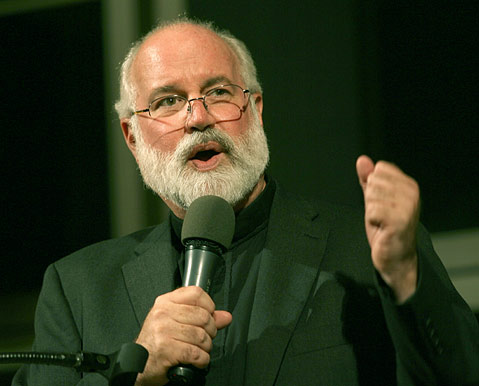

Father Greg Boyle

Father Greg, as he’s known, started Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles in the 1990s, and it has since become a national model for pulling gangbangers out of destructive lifestyles and putting them on a safer path in life. He is sending two of his homeboys, Louis Perez and Fabian Montes, to discuss their life tales, and spent a few minutes last month discussing his work.

How does the Homeboy Industries model work? We have this therapeutic community where people work and have a reason to get up in the morning and, more important, a reason not to gangbang the night before. They come in here to be gainfully employed. : This is a decidedly intervention program about those already in a gang, regrettably, and who now need assistance to get back on track. So we’re not a program for those who need help, we’re a program for those who want help. There’s quite a difference there.

Is there a certain age when gangbangers want to get out? It’s like recovery in any other sense: It takes what it takes. So they can think, “I don’t want to go to prison again,” or, “My son was just born,” or, “My best friend was just killed.” Whatever it is, you get to a place where you say, “That’s it for me.” So we’re here to strike while the iron is hot; if people can come in here, then they’re ready to move on to rebuilding their lives.

Is offering jobs a big component of the success? If you ask anybody what would help, you wouldn’t find one gangbanger who would say something other than a job.

Do you know of other successful models that have used you as an example? There’s not so much a program as there are other cities. Rather than franchise and move to other places, we give technical assistance to cities, from Tucson to Spokane to Prichard, Alabama. We go there, and we help them try to figure out what it is that will work there. They study us and we consult them, so then they start their own thing rather than airlift our program, because we don’t think that would work. This program works because it was born from below. No one airlifted it from Dubuque-it’s decidedly an L.A. thing.

What would L.A. look like without Homeboy Industries? Since 1992, gang-related homicides have been cut in half and then cut in half again. How do you explain that? It’s obviously not one thing, it’s many things. But we are absolutely certain that we’ve been in existence since then. The city, by way of the people, has decided to do a comprehensive approach, and it’s worked. Occasionally, you get city officials saying, “Nothing we do works.” I go, “Where have you been?” It works pretty magnificently. We need to do more of it, and be more concentrated and intentional.

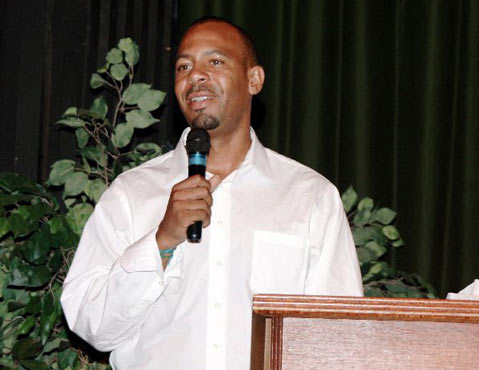

Aqeela Sherrills

As the man who coordinated the peace treaty between Los Angeles’ Crips and Bloods in the early 1990s, Aqeela Sherrills is a well-known force against useless gang violence. After his son was shot and killed in an apparent gang attack in 2004, Sherrills redirected his focus into what he calls the Reverence Movement, which intends to bring spirituality back into modern lives. He talked last month about his work.

What do you plan to talk about in Santa Barbara? I’m going to tell my story, which is about growing up in the Jordan Downs housing projects, getting involved with gangs, and participating in the lifestyle. Then I’ll talk about the epiphany I had when I went to college, and coming to terms with a lot of the wounds in my personal life that actually drove me to gangbang. And then I’ll talk about the transformation I made, organizing the peace treaty in 1992, and the work we did during the next 12 years to sustain that peace process. In 2004, my older son was murdered by an alleged gang member, so I’ll also be talking about the role of forgiveness in that process, not to perpetuate the conditioned social response to deal with violence.

Do you believe that trauma is at the root of gang violence? Absolutely. Gang violence, high school dropouts, alcoholism-they’re only symptoms for deeper problems of individual self-esteem and spiritual disconnect that’s taken place in one’s personal life. Our ability to confront a conflict in many cases infringes on the individual involved with the conflict, and their ability to reflect and deal with stuff that happened to them as a kid. It always comes up-you took my car, and I want to kill you. It’s not so much about your car being taken, but that my livelihood was taken, my dad was taken when I was young. It comes with a whole string of attachments.

How do you get young gangbangers to confront their past trauma? One, you can’t change nobody who don’t want to change. I don’t possess any special powers of magic. I don’t have no goober dust that I’m gonna sprinkle and wake up folks. My story is hopefully compelling enough, and I go into detail about what I experienced, the sexual and physical abuse and how it manifested in my life. Either my story will compel them to reflect on what they’ve experienced or, for those who want to change, one of the things we like to do is connect them with resources, organizations, and individuals doing work in their area. The critical difference is having someone here to extend a hand of friendship and love versus not having any at all. For many of us, as young men coming up who didn’t have fathers, having that positive role model is important. They probably haven’t made all the best decisions, but they’ve set goals and achieved some of those goals. I also like to have the youth and young adults look at conflict resolution as a career path. Gangs aren’t going away-they’re always part of the culture, and not inherently negative. Fewer than 5 percent of gang members actually commit violent crimes or murder, and that percentage has serious mental health issues. We can keep the social structure in place and try to facilitate a dialogue with key players to make the unwritten rules of the street written. Whatever neighborhood you claim, it can benefit the community. Those are the types of things we look at: How we can help to transform these things we call gangs in our neighborhoods?

Mariette Hartley

Simply talking about suicide steals the power away from the damning thoughts that precede this ultimate act of self-destruction. So says actress Mariette Hartley. And she should know. In addition to a life in front of the camera-47 years so far on TV and in movies, beginning with a starring role in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 classic Ride the High Country-Hartley’s life has been plagued by the specter of suicide. Since the late ’80s, however, Hartley has also worked as a suicide prevention advocate, using her Hollywood-born visibility to ensure that the conversation about suicide continues.

Perhaps most recognizable from her recurring role on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, an Emmy-winning role on The Incredible Hulk, and a series of Polaroid commercials she did with James Garner, Hartley explained the start of the winding path that led her to advocacy by, appropriately enough, invoking a TV show: Mad Men. Hartley explained that she, essentially, is Sally Draper, the young daughter of the show’s lead character. Like Sally, Hartley grew up in an environment soaked “in the wetness that alcohol created-and all of the dysfunction.” And Hartley’s father was a real-life ad man, whose list of accomplishments includes designing the Pepsi-Cola logo. However, on July 2, 1963, her father fatally shot himself-an event that itself was bookended by her mother’s two attempted suicides. Despite the trauma, Hartley kept quiet about her father’s death. “My mother swore me to secrecy,” she recalled. “She wanted him known only as an artist.”

Hartley claims acting helped her survive. “I walked around fairly lost and made some inappropriate life choices. The only one that worked was acting. : That really gave me an amazing sense of whatever self I possessed.” Her work-which, notably, included a supporting role in Marnie, the Hitchcock thriller about mental illness and festering trauma-ultimately led her to Silence of the Heart, a 1984 TV movie about suicide. In preparing for the role, Hartley spoke with families who had also endured the suicide of a loved one. Everything changed. “It was very frightening, stepping near this black hole. I felt, ‘God, if I get near this, I’ll be sucked in and I’ll never get out.'” Her fears, however, soon vanished. “I met a couple who had lost their son the same way I lost my dad. We talked about it, hugged each other, held each other. It was such an epiphany. : I hadn’t a clue that there were other survivors in the world,” she said. “One of the problems is the terrible sense of isolation. You feel you can’t talk about it because of the guilt and the stigma.”

Hartley continues to spread those good, life-saving words. In 1987, she helped found the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. She continues to try to inform others about suicide-both those who have already encountered it and those lucky enough to have not. “So many people have no idea that something like this could happen,” she said. “The main thing is to listen. If someone comes up and says ‘I’m feeling suicidal,’ take it seriously. You don’t want it on your brain that, if it does happen, you turned your back and didn’t help. Often, all they need is someone to sit with and talk.”

For her Santa Barbara appearance, Hartley will be speaking about what can be done to help stop suicide. In doing so, and in telling her life story, she’ll also be offering proof that no matter how deeply someone may be hurting, he or she can use that pain to promote mental health. “Many of us get to heaven by backing away from hell,” she noted. Without a doubt, some in the audience will relate and, Hartley hopes, will find their own paths to light.

4•1•1

The Glendon Association hosts its 15th Annual Violence and Suicide Prevention Forum on Wednesday, October 7, at 6 p.m. at the Abel Maldonado Community Youth Center (600 S. McClelland St., Santa Maria) and on Thursday, October 8, at 6:30 p.m. at S.B.’s Marjorie Luke Theatre (721 E. Cota St.). Visit glendon.org for more information.