“Well, I’m still fogging the mirror,” Bob Young told me in September, while tethered to an IV., mainlining one of his alternative treatments. Whatever he was doing, it had bought him more than two years of life from the death sentence that typically comes with pancreatic cancer. Still, his hallmark optimism was leavened with a gritty realism: “They tell me it can’t be much longer,” he said. “We’ll see.”

He had just stopped going to his office on Milpas Street, where he practiced general medicine but was better known as the travel doctor for those needing inoculations and for alternative therapies. A small, elfin man of palpable vulnerability, he grew slimmer with each passing month. Yet he kept treating his patients, few as sick as himself, whose devotion to him rivaled that of a cult. “I’m proud that I practiced as long as I did,” Young told me in his airy Mission Canyon home, where he was surrounded by books, musical instruments, and family photographs, and scrupulously attended to by his wife, Terri.

Young was almost a native Santa Barbaran, having lived here since he was four years old. He been born into a family of doctors and nurses his mother was a nurse, his father an opthamologist, and his grandfather a country doctor in Montana. (“I had an uncle who was the sheriff of Livingston, Montana,” he told me in one of his typical droll utterances, “until he was shot dead. That was the end of him.”)

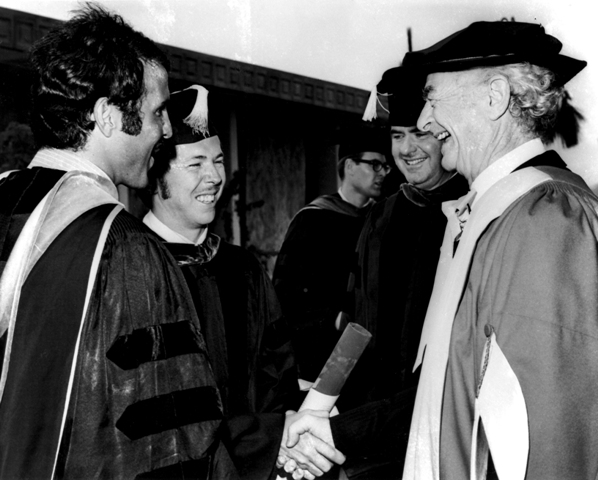

Young graduated from UCSB in 1965 and won a four-year scholarship to the University of Southern California’s medical school. His lifelong idol Linus Pauling spoke at his class commencement; Young pulled out a cherished photograph memorializing his meeting with the great pioneer. “He was my hero,” Young said. “So clear and liberal, politically and socially.” Young interned at Los Angeles County Hospital, in one of the gnarliest and busiest emergency rooms in the country. He delivered more than 100 babies before he left. Then he signed up to work in the wild-and-wooly Los Angeles Free Clinic.

When he returned to Santa Barbara In 1972, Young devoted himself to starting up Cottage Hospital’s emergency room, which remained among his signal, proudest achievements. “When someone comes in the ER, you want to eliminate the worst possibilities,” he explained. “If they have headaches, rule out a stroke or a tumor, etcetera, right away. And that’s the way medicine should always been practiced: You rule out the worst first.”

In 1976, Young started his own private practice in general medicine. It was an intensely busy time, he recalled, running his new practice while raising four children, often on his own. “I was sort of the last guy on the train before the HMOs took off,” he said. “And I don’t think HMOs are ethical. How many people know that the insurance industry spends $1.4 million a day on lobbyists to defeat health care reform?”

Young always thought his real talents lay within the arts-drawing and playing guitar. “I started out as an art major but I wanted to have a comfortable life,” he conceded. On days when his comfort level plummeted, from the stresses of work and a collapsing marriage, he found solace in Santa Barbara’s nightlife. “Me and my friend Al,” he said with a smile, “loved martinis, and beer and all kinds of junk food.”

In 1998, Young met Henry Hoegerman , M.D., a practitioner of alternative medicine who had set up shop on Milpas. Hoegie, as he was known to all, was offering chelation to heart patients and folks overloaded with lead and mercury. He was also investigating an array of alternative treatments for cancer patients and those seeking to offset the side effects of chemotherapy. He emphasized preventive care. “Hoegie was an unbelievable guy,’ he said. “He really got me into nutrition.”

Yet Young never discounted Western medicine, crediting “vaccines and antibiotics” as “the two most important factors in extended life expectancy and quality of life.” No ally to New-Agers who regard antibiotics as a scourge, he pointed out that his “father died of kidney infection because he didn’t get the right antibiotics.” The third greatest factor in revolutionizing health, he said, was simple hand-washing. “It was huge,” he said. “Alexander Semelwies was vilified for suggesting that doctors wash their hands. That’s the way it is. Change is always ridiculed at first.”

Ironically, Young had long worried he would get the disease that he did. “I always feared pancreatic cancer and said, oh please god don’t give me that, even though everyone has to die of something.” It began for him about four years ago with giardi-like symptoms, but in 2005, he was diagnosed with pancreatitis. It would be another year before he learned he actually had pancreatic cancer, which often claims its victims within months.

Young said there was one factor that he was certain contributed mightily to his cancer. “For me, I’m sure it was just stress.”

Young treated himself with his own therapies but he also generously praised to two local doctors, Gary van Deventer and Allen Weinstein, for steering him through the worst of it. “These are great doctors,” he said, emotionally. “Each is a doctor’s doctor, and part of that is that they are kind men.”

About two weeks before he passed, I sat next to him in his livingroom. He looked to be about 100 pounds as he untangled one of his IVs. “Actually, it’s a very interesting experience to contemplate my own demise while I’m circling the drain,” he said, adding. “I’ve been very fortunate.”

Bob Young is survived by his wife Teresa Eddy, four grown children-Maggie, of Camarillo; and Kathryn, Robert, and Susan, of Santa Barbara-three stepchildren, and two grandchildren.

His practice will continue under the stewardship of Dr. Scott Saunders, along with Conchita Hernandez, Dr. Young’s devoted nurse for 30 years, and naturopath Kristi Wrightson.

A celebration of his life will be held at his favorite haunt, the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History in the Fleischman Auditorium on Sunday, November 22, 2009 at 1:00 p.m.