Peace Threatens to Break Out in S.B. Growth Wars

New Height Limits Offered in Exchange for Increased Density

That the Santa Barbara City Council spent seven hours in two grueling back-to-back sessions last week hammering away on Plan Santa Barbara — a sprawling, ungainly, and time-consuming effort to define how much growth Santa Barbara should accommodate over the next 20 years — came as no surprise. What proved genuinely startling, however, was the extent to which the long feuding factions — the so-called new urbanists versus traditional slow-growthers — managed to focus on points of agreement rather than those of contention.

For the past five years, these rival camps have been disagreeing — and often quite disagreeably — over what kind of future Santa Barbara should embrace and for which segments of the community. Superficially, the differences separating these two communities seem silly and semantic; new urbanists and smart-growthers thump the gospel of “sustainability,” while slow-growthers trumpet “living within our resources.” Really driving the debate, however, is a profound dispute — both practical and philosophical — over affordable housing and the lengths to which government can and should go to create housing opportunities for all income levels. New urbanists emphatically embrace increased development size and densities to expand broader housing opportunities. They believe parking has dictated the direction of land-use planning to an unhealthy degree and by reducing resources allotted to the automobile, housing can be made cheaper, cities more livable, and the planet healthier.

By contrast, slow-growthers are skeptical anything can really reduce housing costs and are quick to note how Santa Barbara — where 12 percent of all housing units are price-controlled — still boasts the highest housing prices on the South Coast. More suburban than urban in lifestyle, they’re suspicious of efforts to reign in the automobile and worry that increased densities will succeed only in generating crime and congestion and destroying the urban landscape that’s made Santa Barbara unique. In part, this divide is generational in nature. And it’s often personal in tone. It’s not uncommon, for example, to hear new urbanists disparage traditional slow-growthers as racist, elitist NIMBYs. It’s equally common to hear slow-growthers describe smart-growthers as “developer stooges.”

To say these two sides affirmatively agreed on the compromise blueprint for future growth outlined last week is a stretch. Serious stumbling blocks still remain, and the S.B. City Council — ideologically polarized as it hasn’t been in more than 25 years — could easily fail to find the five-vote supermajority needed to pass anything. But the tone of the discussion was notably less acrimonious. And after two days of intense and often windy deliberations, the bones of a meaningful compromise package emerged that might just defy the political odds and achieve the limited consensus required.

Failsafe Strategy

One of the key proposals on the table would effectively restrict the height of most new buildings to no more than three stories. The City Charter currently allows no more than 60 feet. The incendiary issue of building height was the focus of last November’s Measure J initiative, placed on the ballot at the instigation of old-school slow-growthers — exemplified by Citizens Planning Association, Allied Neighborhood Association, and the League of Conservation Voters — and new-school conservatives, outraged at the violence they say has been inflicted on Santa Barbara’s skyline and historical character by the architectural behemoths sprouting up along lower Chapala Street. Although Measure B (which would have prohibited any new development more than 45 feet high in El Pueblo Viejo) was trounced at the polls, concern over the mondo condos that gave rise to the initiative in the first place remains alive and well.

In exchange for the new height restriction, the compromise proposal would allow much more densely packed residential development in commercial downtown areas than city law now permits. On the table is a plan that would allow double the residential density currently allowed in downtown commercially zoned neighborhoods, and under exceptional circumstances even more than that. Commercial densities would be reduced to one-third of what’s now permitted. In addition, it would grant a 50-percent density bonus to developers proposing rental housing. New urbanists — exemplified by the Community Environmental Council, SBCAN, and PUEBLO — architects, and developers insist this density increase is a necessary precondition for the development of affordable housing. Exceptional steps are required, they insist, to allow necessary workers — firefighters, cops, teachers, and nurses — to call Santa Barbara home. If these people are effectively excluded by the high cost of housing, Santa Barbara will devolve into yet another Guccified, exclusive coastal community.

In addition, the proposed compromise has targeted the one issue on which the slow-growthers and new urbanists seem to agree; they both hate the luxury mega-condos, which have been encouraged by the city’s existing planning and development guidelines. The slow-growthers are alarmed by the looming size of these condos. And new urbanists — who want to maximize Santa Barbara’s limited development potential for affordable housing — are appalled by their costs. To this end, the compromise plan, which was first embraced by a solid majority of the city’s planning commission on June 3, calls for an assortment of carrot-and-stick strategies that will reward developers trying to build smaller, more affordable units. The new ideal has evolved to be 1,000 square feet. In addition, it calls for punitive regulatory and pricing strategies to discourage downtown mini-mansions. The hope is that by pushing for smaller unit sizes, city planners can reconcile the seemingly incompatible objectives of housing affordability and visually low-impact design.

As proposed, the new height restriction and density limits are not quite written in stone. Under certain circumstances, buildings taller than three stories could still be allowed. And individual buildings three times as dense as what’s now allowable could still be approved. But such projects would be required to meet a much higher threshold of approval. To ensure that elected officials — and city hall — have not given away the store, certain key failsafe provisions have been inserted into the compromise plan. Any developer seeking more than three stories — or densities beyond 40 units per acre — would have to obtain supermajority votes from both the city council and the planning commission. That means five councilmembers — not four — and four planning commissioners — not three — would have to approve.

This safeguard marks a new and dramatic extension of protections that are currently on the books with more limited application. More than anything else, its inclusion helped cool the often flaring tempers surrounding public negotiations over proposed changes to the city’s general plan. Ironically, this supermajority idea was suggested by one of the hottest heads and impatient voices surrounding the debate — Planning Commissioner John Jostes. A high-powered, high-stakes, globe-trotting public-policy mediator by trade, Jostes was not shy about publicly voicing his intense dissatisfaction with the slow pace and lack of focus of the general plan update process, now in its fifth year. So relentless were his complaints that among key city planners Jostes came to be seen more as a grating vexation than credible critic. But without Jostes’s last-minute interventions, it’s highly doubtful there’d be any proposal under consideration that could salvage all the time and money — $2.2 million to date not counting staff time — spent by city hall on this arduous planning exercise.

With a supermajority failsafe in place, the hope is the opposing camps will feel confident they possess an honest shot to make their case. New urbanists and so-called smart-growthers would know a genuine possibility existed for new innovative developments that required a degree of size, bulk, and scale not countenanced by those more concerned about preserving Santa Barbara’s small-town charm. And slow-growth advocates — worried about the intensification of urbanization — would enjoy the security of a strong line of defense. As Councilmember Dale Francisco, an ideological conservative and slow-growth neighborhood preservationist, noted, “If we can’t manage to elect five sane people to the city council, then we deserve what happens to us.”

Shout-Out from Texas

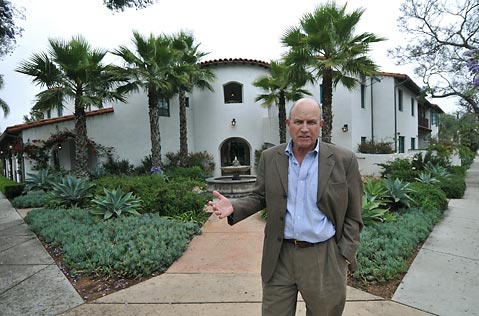

Perhaps the most striking endorsement came indirectly from Randall Van Wolfswinkel, the polarizing Texas real estate billionaire (and part-time Santa Barbara resident) who spent an unprecedented $750,000 in last November’s city council elections on behalf of a conservative slow-growth slate and Measure B, the stricter building heights limit. At last Tuesday night’s meeting, Van Wolfswinkel’s land-use agent, Raymond Appleton, announced that his client was pleased with the new de facto three-story height limits now under consideration. In fact, said Appleton, had Van Wolfswinkel known the council was moving in this direction, he wouldn’t have spent so much money on the council race.

But that money can’t be unspent, any more than the city council candidates elected to office because of it — Michael Self and Frank Hotchkiss — can be un-elected. Of all the council members, Hotchkiss and Self are the most openly hostile and suspicious of Plan Santa Barbara. Hotchkiss, for example, demanded that all references to climate change and global warming be expunged from the document. (Councilmember Das Williams cautioned that without such references, any final plan would be vulnerable to legal challenge by the California Attorney General, who has sued several cities for failing to address climate change.) Likewise, Hotchkiss wanted the entire chapter on the public health implications of land-use planning — air pollution, congestion, childhood obesity — deleted. Instead, he said the plan should be predicated on preserving “things that made us want to come here in the first place,” notably Santa Barbara’s historic beauty and charm. Hotchkiss was less than enthusiastic about portions of the plan dedicated to preserving the city’s existing rental stock; he wanted a limit set on the amount of affordable housing city hall wanted built, and to the extent government intervened in the housing market, he said, it should be to encourage home ownership. Hotchkiss was most vociferous, however, in his opposition to strategies designed to discourage reliance upon the automobile as a primary means of transportation. “Planning that attempts to force people to give up a modern convenience, such as use of a car, is offensive and authoritarian,” he said.

Sauerkraut and Split Pea Soup

Hotchkiss was referring to the most contentious elements of the proposed plan: to accommodate new urban densities by promoting bus riding, biking, and walking while strongly discouraging the automobile. To this end, the plan calls for reducing the amount of parking spaces developers must provide. It would also allow them to provide a portion of their required parking spaces offsite. Supporters refer to this — in the jargon of planner speak — as “de-coupling” or “unbundling.” By reducing parking requirements, they argue, housing costs are lowered. And this, they argue, will make it more economically possible for developers to build affordable — also known as “workforce” — housing. Critics, however, dismiss this as a pipedream conjured by utopian-minded urban planners. They worry that people would still drive cars as much as they ever did, and that residents of this new housing would cannibalize public streets for their parking needs.

Likewise, the plan calls for a sustained assault — carried out over time — on free parking. Traffic engineers contend there’s no more effective antidote to traffic congestion than what they term “priced parking.” Rather than pay stiff parking costs, shoppers and workers alike would find ways other than the car to get downtown. This would take a serious bite out of escalating levels of congestion that now threaten to take no less than 12 major downtown intersections to below-acceptable levels of service. But few cows are as sacred as free parking. Downtown merchants and property owners argue priced parking would also kill business downtown. Given the hundreds of millions of dollars city hall has spent revitalizing its downtown over the past 20 years, that would make no sense.

Even more sweeping in her criticisms was Councilmember Michael Self, who suggested that the proposed document was too sweeping, too vague, and too open to interpretation by agenda-driven city employees seeking to expand their job description with new programs to manage and edicts to impose. “It’s like mixing sauerkraut and split pea soup,” Self said of the plan. “That’s what you end up with, too much vaguery.” Self expressed concern that increased densities would generate big-city traffic congestion and crime. Of all the council members, Self expressed the least concern about the impacts of high housing costs. There was little call, she said, to protect or augment the city’s aging rentals because the rental vacancy is currently high. “We’re addressing a problem that isn’t there,” she declared.

Councilmember Bendy White — a planning commissioner for 14 years — managed to get elected last November despite being targeted for defeat by Van Wolfswinkel. A major force in pushing the compromise language, White had hoped to persuade Self and Hotchkiss, in particular, that the status quo was no longer acceptable, allowing, as it does, 60-foot buildings bulging with oversized luxury condos. Self didn’t buy it. She said it was not the city’s place to regulate such development, saying of people who bought high-end condos, “These are people who more support what this city is about, the arts, the culture.”

Barring a dramatic change of heart, it’s extremely unlikely Hotchkiss or Self could vote for anything resembling the current compromise. Given that five votes are required to pass the general plan revisions, that leaves conservative Councilmember Dale Francisco as the key swing vote. Councilmembers White, Williams, Grant House, and Mayor Helene Schneider all expressed strong support for many of the plan’s components. Williams’s continued tenure on the council remains unlikely. He’s heavily favored in his race for State Assembly against Republican Mike Stoker. If he wins, Williams would step off the council in January, one year before his term expires. Should that occur, the existing council would appoint William’s successor. Given that the council would then be split 3-to-3, it’s hard to see how any replacement candidate could pass muster. Given this, the council majority supporting the plan feels a keen sense of urgency to get something approved before Williams departs. But Francisco, who wields the tie-breaking vote, has made it clear that he won’t be hurried or steamrolled. “I can’t possibly support anything that the council hasn’t thoroughly reviewed,” he said. “Thoroughly.”

While supporters of the compromise plan worry that Francisco might be inclined to slow the process down for political advantage, he has already displayed a willingness to engage constructively and make calibrated compromises on planning policies he viscerally opposes. For example, Francisco has consistently condemned inclusionary housing rules — which require developers to sell 15 percent of all new units at below-tmarket rates — as “extortion.” The new plan would increase that requirement to 25 percent. But Francisco said he could support a plan — proposed by Councilmember White — to inflict such fees on high-end developments but spare lower-end projects. As White said afterward, “Dale is holding all the cards. And he knows it.”

Stay tuned. After five years of deliberations, the debate is just starting.