Stopping the Direct-to-Consumer Flow?

Federal Alcohol Distribution Bill Worries Winemakers in Santa Barbara and Beyond

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story was updated to include comments from the Wine and Spirits Wholesalers Association.

As everyone sips their rosés and sauvignon blancs under the summer sun, a bill sits in Washington, D.C., silently threatening the U.S. wine industry. In fact, the passage of HR 5034 would hinder all domestic fine alcohol and beer production, limit consumer choices, and compromise the integrity of the U.S. Constitution — all for the benefit of alcohol wholesale companies. Those wholesalers, however, say that the bill merely tries to clarify the existing federal law so that state legislatures maintain regulatory control over alcohol distribution.

The bill — crafted by the National Beer Wholesaler’s Association (NBWA) and the Wine and Spirit Wholesalers of America (WSWA) — would give each state the power to create its own alcohol shipping laws. If passed, states could discriminate between in-state and out-of-state trade, which would be a violation of the Constitution’s weighty “Commerce Clause” that maintains healthy competition among states. Because many wineries rely on the ability to ship directly to consumers — with some even building their entire business plans upon it — the passage of HR 5034 could put wineries in a situation that the Wine Institute’s communications director Nancy Light calls “dire.”

“It’s such a sweeping bill,” she explained. “[The current system makes it] viable for a winery unable to find distribution to be able to get their wines to consumers.”

Jim Fiolek, executive director of the Santa Barbara County Vintners’ Association, explained that it affects “every single one of our [more than 110] members,” even spelling disaster for many. Will wineries go under as a direct result of HR 5034? “Instantly? I doubt it,” said Fiolek. “Over time? Certainly.”

Also called the Comprehensive Alcohol Regulatory Effectiveness Act (CARE), HR 5034’s acronym attempts to appeal to lingering post-Prohibition angst in Congress, where its backers have donated $11.5 million to various congressmembers’ election campaigns. But Fiolek laughs at the public safety position that the wholesalers are using, asking, “How many kids are going to steal their parents’ credit card, spend 300 to 400 bucks on a case of wine, and have to sign for it?”

The bill would also make the new legislation irreversible, permanently overturning the 2005 Supreme Court decision that established the power of the “Commerce Clause” and made sure that states regulated in- and out-of-state alcohol purveyors evenhandedly. “This bill goes much farther than direct shipments,” warned the Wine Institute’s general counsel, Wendell Lee. “It doesn’t just give states the power to pass laws without having to worry about [interstate] discrimination — it gives states the power to pass laws that might conflict with any act of Congress.”

In fact, CARE’s collateral implications are so extreme for the nation’s interstate trade system that Lee believes its supporters simply don’t understand it. “A lot of legislators don’t have the historical and legislative context of alcohol distribution,” he said, noting that many likely signed on coaxed by “generous contributions” from wholesale companies. “But I think anyone who really does analyze it would think twice about supporting it.”

But Craig Wolf of the WSWA argues that there’s much more than wholesalers’ wallets behind the bill. Since the 2005 decision — which CARE would strengthen rather than overturn, said Wolf — there have been more than 50 lawsuits against individual states over alcohol laws, leaving judges’ decisions to become the rules. That’s created confusion and conflict between jurisdictions, and has resulted in a general trend of deregulation for the country’s alcohol industry, said Wolf, who said CARE is simply attempting to provide better guidelines for decisions when a law is challenged. “Not one state law would be overturned by this legislation, not one,” said Wolf, whose organization is politically opposed to direct shipping but supports state’s rights to do so. “Mostly, the law is going in favor of proponents of direct shipping.” Wolf said those opposed to CARE have “outspent us 20 to one,” explaining that both suppliers and retailers stand to profit from a further deregulated alcohol industry that cuts out the wholesaling middlemen that were created by the 21st Amendment.

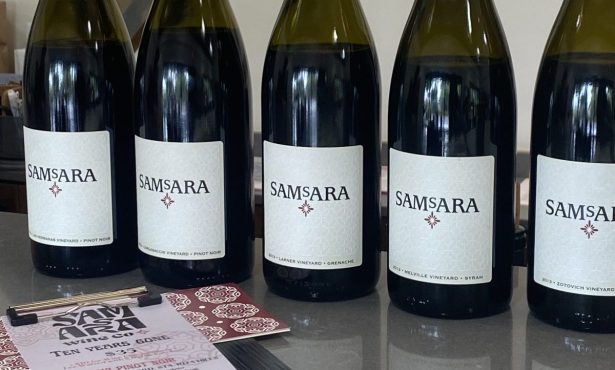

Direct shipping has been critical for many wineries’ financial health due to the difficulty in finding a distributor willing to represent them in the first place. “The distributors have too many wineries and don’t want anymore,” said Fiolek. “They can’t handle it.” Effectively, if passed, the bill would block countless numbers of America’s 7,000 wineries from selling wine to customers in another state forever. “To me, that’s the crime,” said Fiolek, noting that the county’s wine industry provides 5,000 jobs and accounted for at least 16.5 percent of the county’s 8.5 million visitors in 2008, according to one report. “When you throw in agriculture, tourism, and hospitality and how wine integrates all of these, you don’t want to do anything to weaken wine,” warned Fiolek. “You have put your entire county in harm’s way.”

Altogether, critics of CARE argue that it affects all Americans by threatening the freedom of interstate trade, undermining the strength of existing federal law, and allowing two commercial associations to permanently change the Constitution and overturn a Supreme Court decision due to the influence of their monied lobbying. So, at the very least, if you want to continue sipping your favorite summer wine, speak up now or forever hold Charles Shaw.