A Center Stage History Tour

Center Stage Theater Turns 20

Center Stage, the small theater at the top of the stairs in Paseo Nuevo mall, provides a service to Santa Barbara that goes way beyond simply offering interested parties an opportunity to put on performances.

Born during a period when many bold new theater and dance artists were searching for a venue that could meet their need for an experimental space, Center Stage Theater embodies the surprising mainstream success of an avant-garde idea, the so-called black box theater. Closer in many respects to the design of a television studio than to that of a traditional proscenium theater, the black box concept came about as performers, directors, and audiences alike sought a new way of communicating, something more direct, more immediate, and less predictable. Now ubiquitous, black box studio theaters were rare before the 1960s, and the arrival of this public facility as part of the city’s deal with the Reininga Corporation for the construction of the Paseo Nuevo ushered in a new era for theater and dance in Santa Barbara.

This Saturday, August 21, many of those who were involved in the planning and use of Center Stage during the past 20 years will gather there for a night of performance, memories, and laughter as Devin Scott and Nancy Nufer host a revue written by Rod Lathim to tell some of the stories that have made Center Stage so important to the community.

In the spirit of that event, and of this wonderfully democratic space, The Independent has prepared a collage of quotations designed to give a brief history of Center Stage. Many more stories exist than it was possible to gather in a short time, so the following is presented as an admittedly partial and incomplete record. Readers who have participated in the life of Center Stage are invited to visit independent.com, where they, too, can contribute to the record of this extraordinary institution.

Black Box Background

Julie McLeod, Santa Barbara Dance Pioneer

Twenty years ago, I started a nonprofit called Santa Barbara Presents; the name then changed to Art Without Limits, and we couldn’t find a really good space. We tried galleries, we tried warehouses, we tried storefronts, and nothing was quite right for what we wanted to do. So we formed a group, and we took some of our own money and contacts — for instance, Pat Fish went into her bag and pulled out all her contacts — and we raised some money that way. And then we went to the city council, and they were interested, but they wanted a study done, and they said it would cost $30,000, and that was the Bailey study. And so the study came back with the news that, surprise, there was not an appropriate space to develop in this way in all of Santa Barbara. The types of buildings that were being converted in other cities for this purpose — we just didn’t have that infrastructure. But then the city council came back again, this time with the news that they had entered into a business relationship with Reininga Corporation for the construction of Paseo Nuevo, and as a result, they were in a position to negotiate for the construction of what would become Center Stage Theater.

Now I don’t know that this wouldn’t have happened even without the activity that had preceded it. We might have gotten the theater anyway, but the fact is that we had already been studying for some time this situation, and we knew what we needed, and it was this size theater — about 100 seats — and a black box space.

Tal Sanders, Lighting and Set Designer

If you think about the groups at the time (1990), and what choices they had, it was really either Casa de la Raza or the Natural History Museum, and neither was exactly right. I can’t tell you how many shows I designed, and then when I finished the set, I’d look up and there would be that same canoe over everyone’s heads. The other thing to remember is that for the locals, the concern over the building of the Paseo Nuevo was intense. People were very upset by the idea of this mall and the gentrification of downtown, so Center Stage was an important part of accepting it, because it was like taking something back for the community from this corporation that was coming to town.

Rod Lathim, Director

Until Center Stage existed, the city really didn’t have any kind of experimental theater space. And Paseo Nuevo was a big deal, because it displaced Piccadilly Square, which was also a mall, but a lot funkier, and when this monstrosity was being planned, that was a hard thing for a lot of us to take. A committee was formed that included myself, Patrick Davis, Eric Larsen, and some other people, and we got support on the city council from Harriet Miller. This was before she became mayor. And we sat down with the folks from Reininga Corporation, the original backers and builders of the Paseo Nuevo, and right away, it became clear that they were thinking that they could just give us four walls somewhere and that would be it. But you know, four walls do not a theater make, so we had to negotiate. We said that they would have to equip the space with lighting and sound and seating, so that it could function as a real theater. And I will always remember this response because it was so funny — one of their representatives said, in this dreamy voice, that his “vision” for the theater was “a guy on a stool reading Mark Twain out loud.” That still makes me laugh. And I don’t know if that ever happened or not, but certainly one aspect of what Reininga expected was not fulfilled, or at least something different happened, because the other thing they kept insisting was that the theater be “family-friendly.” They said it over and over, “a first-class mall that’s family-friendly.” Well, there have been loads of wonderful family-friendly shows in the space since then, but everybody who was behind it knew that it was going to be used for all the crazy stuff, and that’s exactly what happened. In terms of content, Center Stage immediately turned into the edgiest place in town.

Behind the Scenes

Tal Sanders

One of the things you should know about working at Center Stage is that it’s a staff of two or three people at most, and so the technical director and the manager are both very, very busy. The main reason it’s so hard is that it may be Tuesday for you, and you’re on the fifth event of that week, but for the person you’re working with, this is the biggest night of his or her life. For them, it’s the only show there is, so you have to give it everything you’ve got.

Brad Spaulding, Current Technical Director of Center Stage

Bird’s Eye View went up as part of the Lit Moon World Theatre Festival in September of 2004. A Russian company did it, and they carpeted the stage floor in white feathers. To this day, we are still finding feathers from that show hiding in the theater. I will move a piece of furniture and out will float one of those feathers. For the Lit Moon production of Shakespeare’s Henry V in 2000, there was a big box onstage, about six feet by six feet, and it was full of dirt. And sometime in the first act, the sides of the box collapsed. So the entire second act I was just sitting up in the booth, watching that dirt being spread everywhere. And it was kind of like with the feathers, because we were still finding it for weeks afterward.

The Impact of Center Stage

Bill Anderson, “At This Stage …” January 23, 1992 Independent Commentary

As this unique creation of Santa Barbara politics and profits, Center Stage Theater is more than a new cultural venue. It is an investment by all of us into that stuff the romantics describe as the only thing that really matters — personal expression and imagination. I would say Center Stage Theater is a place where people can come together to communicate. Whether to make art or chew the fat, to observe or take part, Center Stage Theater is Santa Barbara’s new and unfettered platform for discovery. It is our place.

Tom Jacobs, Theater Critic

My introduction to Center Stage was also my introduction to Lit Moon Theatre Company. I came to town in 1994 from Los Angeles, where I had been reviewing for the L.A. Times, and one of my concerns was that things would be conservative aesthetically, and possibly not of the highest quality. But I saw the Lit Moon Alice in Wonderland in 1994, and it was a great experience. The production was so imaginative, and the acting was really good. Since then, I think it’s fair to say that I’ve seen some of the best and some of the worst theater in my life in that room. There was an evening of 10-minute one-acts at one point that was just all over the place, with each play directed by a different person, and I thought it would never end.

Maurice Lord, Director of Genesis West

For me, it all began when I was helping out Bob Potter on this evening he was producing all these kind of random short one-acts. I was just a student of his at UCSB at the time, and he threw me in there and put me to work. Since then, I must have directed 20 shows at Center Stage. I love the black box — that’s the only kind of theater I have ever wanted to do. And Center Stage has always been so accommodating. Even when Todd Patrick was there as the tech director, he would work with me and help me realize my vision, despite all the crazy demands I was making. I learned from Todd how to be organized, and how to make a list so that the tech director could understand me and see what I was trying to do.

Teri Ball, Current Manager of Center Stage and Speaking of Stories

The mission of the space is very simple. It’s to be here to provide a theatrical space for the community. We offer it very much on a first-come, first-served basis. There are different rates for for-profit and nonprofit groups, but the mission is the same, to be a theater space for the community. We can serve all kinds of people, and in a less intimidating way than the larger theaters. What I like is that we get to teach as we go. Particularly with the young groups that come through, I like to think that they know more about putting on a show when it’s over than they did when they came in here. One of the great things about Center Stage is one day you’ve got six-year-olds doing Annie Get Your Gun, and then a week later, it’s professional actors doing Frost/Nixon, and in between the two performances, the theater is being used as rehearsal space for an opera workshop.

John Blondell, Director of Lit Moon Theatre

The community needed this kind of theater not just because it needed a space, but also because it needed this kind of space. Black box theater is a revolution in the relationship between the performance and the audience that’s been so successful that it’s almost taken for granted. It’s only been 50 years, but it has even become conventionalized. But in this instance, it’s a good convention, because it’s what has made theater so appealing for a new generation. That’s because there’s not this “Two minutes, Mr. Blondell” thing going on anymore. What happens is more right in front of you. Black box is the opposite of the theater as a place where the wealthy go to see stars; it really democratizes the whole experience. And the great thing about it, here in Santa Barbara and elsewhere, is that the result is not only the inclusion of all these people who could maybe not afford to construct professional sets for a proscenium theater, but the unexpected gift to these same people which the black box gives in that it asks performers to substitute using their imaginations for some of the things that they left behind in the old fourth-wall theaters. So in addition to just having more people doing theater, you get more imagination coming into the theater from both sides — from the performers, who have to find new ways to convey their meanings, and from audiences, who have to figure out what is going on in these new kinds of plays.

We [Lit Moon Theatre] would not be what we are, and we would not look like what we look like, without the Center Stage Theater. It’s something that’s true throughout the history of theater. Shakespeare’s art was what it was because of the raised platform stage in Elizabethan England. Small spaces with flexible configurations are the basis of a different understanding of the relationship between the performers and the audience, and that understanding is more representational than presentational, more intimate, and more direct.

Santa Barbara doesn’t have a typical community theater situation, and one of the things that I find fascinating is that Santa Barbara does community theater its own way, because for us, it’s blown apart and then reconstituted in these constellations of maybe more creative, certainly more idiosyncratic organizations, and that couldn’t have happened without Center Stage.

The NEA Four

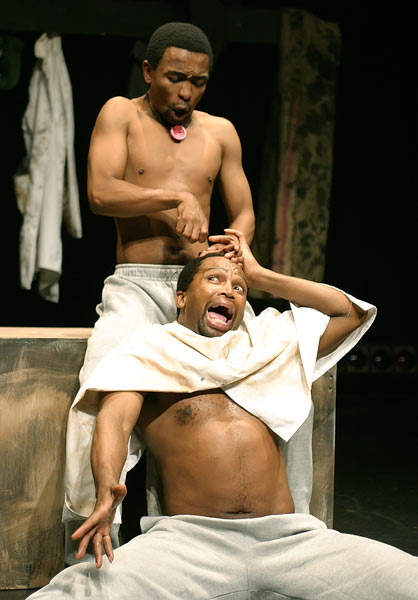

In September of 1990, the Santa Barbara organization ArtCom held a meeting at which opinions concerning the recent attacks by senator Jesse Helms on the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) were aired. Paul Iannaccone, director of the Santa Barbara Civic Light Opera, said that he thought the NEA had an obligation to exert some kind of control over the work they sponsored. Betty Klausner (the first director of the Contemporary Arts Forum) responded by announcing that Tim Miller (pictured above), one of the “NEA four” who had lost funding in the controversy, would appear at Center Stage as one of the first shows in the space. His piece, Sex/Love/Stories, was performed on September 24, 1990, as the fourth event to take place in the Center Stage Theater.

4•1•1

The Center Stage Theater 20th Anniversary Celebration will be held at Center Stage on August 21 with a reception at 7 p.m. and a performance at 8 p.m. For more information, visit centerstagetheater.org or call 963-0408.