A Visit to the Clark Estate

One Saturday Morning in 1958

Huguette Clark is very much in the news currently. She is the owner of the intriguing mansion that looms above East Beach and across from the Andree Clark Bird Refuge, the “duck pond” donated to the public by the heartbroken Clark family when Huguette’s sister died very young of meningitis.

There are investigations now regarding Huguette’s condition and finances as the subject of her will is discussed, but it appears clear that she has had good treatment. After all, she is 104. She has been a reclusive person all these years and evidence recently brought forth verifies the impression I got from her home that she is also sophisticated and highly educated, a gifted artist and lively, passionate musician with a generous heart. Underneath all the secrecy must be a fascinating, self-preserving woman.

A strange phenomenon, described in some pieces of literature I’ve read through the years, is now kicking in as I turn 70. I can select different times of my life and, like putting something into a search engine, find that moment and recall the event with near crystal clarity. It’s one of the little perks as the experience of old age unwinds.

Here is my memory of visiting Huguette Clark’s home one Saturday morning in 1958.

Lights were bouncing off the water on the big pond, which curved to the left as a hillside loomed up on the right behind a stone wall, behind which, up the hill, was the caretaker’s house. Solidly perched, it looked like an oversized country cottage, emerging starched white and stiffly maintained, with trees and gardens terraced beyond. Out came a sizeable man who greeted us with stern manners. We were about to tour the Huguette Clark estate, a place almost no one had ever seen inside.

It is a wonder we were able to do this. Richard Phipps, now an important painter, and I were students in Lindberg-Hansen’s art history class at UCSB. The professor was an expert in many areas including tapestries and at the request of Huguette Clark had brought some seamstresses over from Holland to repair the brilliantly stitched pieces that were on the sofas and chairs in her sitting room. (They were vintage Louis XV.) I did go to the house several times while the ladies were working but I sat on a chair in the entry and was warned not to go anywhere else. The caretaker offered to give me a tour.

The day came. The three of us, the caretaker, Richard, and myself, proceeded up the hill to the mansion’s forecourt with its vast Pacific Ocean view (then glimmering with massive pools of silver light layered on shades of aqua edged with deep cerulean). We began by looking through the big sitting room to the right of the entry. Large Aubusson rugs lay on exquisitely crafted parquet floors, their fanciful colors, raspberry, many pinks, and variations of green, creating lovely floral motifs on a field of cream. The room was filled with antique furnishings, and the overall impression was of a giant jewelry box opening.

On to the library, a long room paneled in cream wood and looking out toward the foothills, with the cemetery next door hidden beyond a green wall. Exciting books sat quietly on countless shelves while I fantasized about the days it would take to open and expose each one.

We next entered a small room completely covered with walnut paneling said to have come intact from a famous chateau. A Renoir and several Impressionist oils ornamented a rich decor in dark greens and burgundy plaid. Funny to me at the time, I recall the caretaker said the ladies used this as a TV room.

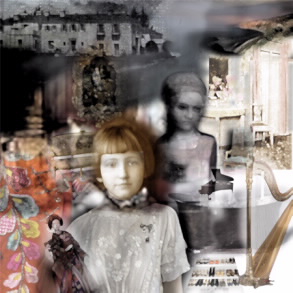

Then came the best: We entered Huguette’s tall-ceilinged, pale yellow art studio. It had multi-paned windows at one end and a huge wall made of shelves that held, as we discovered by opening some of the many boxes on each one, a fabulous collection of Japanese dolls. An easel was set up, with drawers full of paint tubes and perfect brushes. Huguette showed some of her finely detailed paintings of these vintage dolls at the Corcoran in 1928.

Upstairs, I remember the mother’s pale yellow and lavender bedroom. An air of sadness lingered around a poignant bust of the daughter who died, placed reverentially on a pedestal before windows that framed an unforgettable expanse of ocean. There was a small baby grand displaying a beautiful Spanish shawl, a harp at its side covered in a case. A most remarkable thing was to see Mrs. Anna Clark’s shoes, maybe 30-plus pairs, lined up in a hall closet, the finest styles from the 1920s and ’30s.

Her Rolls was up on blocks in the garage. My mother later described the way the townspeople would see the old woman being driven along the beach front around 3 o’clock each afternoon. It is said she had no friends but some recall her association with the notoriously fun-loving Ganna Walska, so there must be more of her story to uncover.

Mr. Clark’s bedroom was English in style, with a walnut bedstead, red draperies, and an astounding gold-plated tub in his bathroom. I went to the rose garden for a quick peek but was motioned on.

As we left, the caretaker said that Huguette had not come in many years but that they were expecting her and a group of her friends in a month or so and he had much to do in order to be ready for this rare event. Reportedly they never did come.

Sherry Howard Stockwell is in an eighth generation of granddaughters directly descended from Thomas Jefferson. she is noted for reviving her landmark Masini Adobe in Montecito, which has hosted Santa Ynez and Central Coast winemaker dinners. Stockwell is also famous for her top-rated web log, “Jefferson’s Table,” and her new cookbook, Cuisine Americana, Eight Generations from Jefferson’s Table.