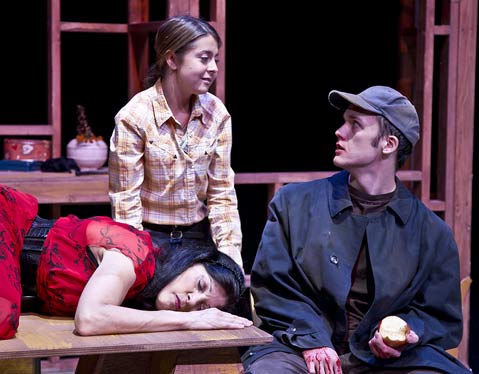

Curse of the Starving Class at Center Stage Theater

Genesis West’s Dark, Absurdist Tragedy Runs Through November 20

Since founding Genesis West, director Maurie Lord has been staging consistently dark, surreal theater, with varying results. This time, he’s hit the jackpot.

Like Lorraine Hansberry’s classic American drama, A Raisin in the Sun, Sam Shepard’s absurdist tragedy, Curse of the Starving Class, concerns itself with deferred dreams and their explosive consequences. But while the tension in Raisin arises from its social and political setting, the volatility of Starving Class is archetypal. The Tate family’s not just poor; they’ve slipped so far from loving interactions that their lives are bereft of meaning. From the opening scene in which teenage Wesley picks up pieces of the door his father drunkenly smashed the night before, the play is a nightmarish slide from very bad to much, much worse.

The action takes place in the kitchen of a ramshackle house on a neglected farm. Ted Dolas’s set gives the place a sense of squalor—conduit winding haphazardly through gutted walls, a plastic bucket to catch the sink water. But even worse than the house is the behavior of the people who live there.

As Weston, the supposed head of this dysfunctional family, Tom Hinshaw is brilliant, swinging with frightening ease from pathetic, drunken ramblings to violent eruptions to magnanimous moods. His wife, Ella (Meredith McMinn), has learned to be tough, at least on the outside. She taunts Weston when he’s passed out and flees when he’s awake. So desperately does she plot to dupe her husband that it eclipses any instinct she might once have had to nurture her children. As Emma, Amanda Berning is the fierce, intelligent daughter whose visions burn too bright; her older brother, Wesley (Merlin Huff), seems destined to follow his father’s toxic example.

If these characters are archetypes rather than people, the empty refrigerator is a symbol of this family’s spiritual starvation. The appearance of groceries near the end of the play doesn’t fill this kind of emptiness; by the time Wesley kneels at the fridge door moaning and tearing at a head of lettuce with his teeth, it’s frighteningly clear that the chance to be fed in any lasting way is long gone.

In the end, it’s hard to know which is the worse fate: to inherit this family’s curse, or to be annihilated in the attempt to escape it.