The Truth Behind the PBS/KCET Split

Why L.A. Station’s Defection May Be Bellwether for Friction Nationwide

It’s been nearly a month since a new TV station started piping PBS shows into Santa Barbara homes after KCET dropped the popular lineup, but the real reason the two organizations went their separate ways after 40 years together is only now becoming clear. And while many of the issues that sunk the relationship are specific to this particular divorce, there are other facets that may point to a larger, developing problem between PBS and its 354 member stations across the country.

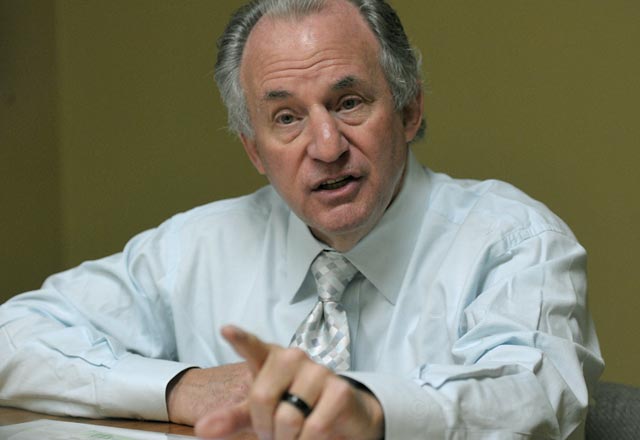

Al Jerome, CEO and president of KCET, recently drove up from his Los Angeles office to sit down with The Independent and explain in his words, which were backed up by the documents he brought along, what went wrong and why. Emphasizing that he doesn’t harbor any grudges — and expressing a desire to look forward rather than back — Jerome nevertheless took the opportunity to break down, play-by-play, what caused the rift.

The reason his station decided to move away PBS, he said, was not because KCET thought it could and should do without shows like Nova, Masterpiece, and Frontline — as some industry insiders have alleged — but because the Public Broadcasting Service unfairly increased KCET’s yearly membership fees just before the economy tanked, was “completely intractable” during negotiations, and made it impossible for KCET to remain a carrier because of PBS’s archaic dues formula and alleged pig-headed management.

This perfect storm of stubbornness left KCET no other choice but to pull out or face bankruptcy, said Jerome, a former PBS boardmember, and could be indicative of why 74 percent of PBS’s member stations have had operational deficits in the last three years and why the system as a whole has been losing money since 2002. “In other words,” said Jerome, “we’re not the only station that has been challenged.”

A spokesperson for PBS said the provider similarly prefers to keep its focus ahead — “Rehashing negotiations takes away from our focus: providing the people of Southern California with high-quality PBS content,” said Anne Bentley, corporate communications vice president, in an email — but refused to address Jerome’s claims and accusations at all.

Wrongfully Reprimanded?

The road that led to this year’s switch — when Orange County-based PBS SoCal, formerly KOCE, took over PBS programming for the South Coast on January 1 — began back in 2007, said Jerome. At that time, KCET came into a windfall of earmarked cash when it raised $50 million to support five years’ worth of production for its award-winning preschool caregiver program A Place of Our Own and its Spanish version Los Ninos En Su Casa. But the money, while clearly a shot in the arm for that specific show, boosted the amount KCET had to pay in overall PBS membership dues pursuant to its fees formula.

When a station produces a show for PBS, explained Jerome, it gets a credit against its yearly dues, which are primarily determined by the amount of nonfederal funding the station generates. (All public stations receive community service grants from the government.) But if the station produces for a local audience — in this case the caregiver show was only offered to California audiences — no credit is given. Plus, Jerome said, PBS fees must come out of a station’s net operating revenue, the total of which is determined by taking a station’s gross income and deducting restricted funding (like the $50 million for A Place of Our Own), leaving only discretionary money used to pay salaries, maintain facilities, and shell out PBS’s take.

Jerome said KCET immediately raised a protest with PBS when its dues were set to skyrocket because of the windfall, which could not be offset by the production of A Place of Our Own, since the series was not for the national market. KCET presented materials that showed the station was actually being penalized for producing its own content — a strategy that, according to other sources, PBS knowingly employs — and asked for a reevaluation of the longstanding dues structure. “We became aware that PBS knew there was a punitive aspect when you raised a lot of money for local production that was not done for PBS,” said Jerome. The effort, however, was to no avail. “They evaluated everything and at the end of it concluded nothing,” said Jerome. “They agreed to no change at all.” In fact, KCET was forced to stand back and watch as its yearly dues eventually jumped from $5 million to $7 million.

It wasn’t long after that the economy took a nosedive and KCET found itself in even more trouble. As the station’s fundraising sources — major gifts, membership donations, corporate underwritings, and foundation grants — shrunk significantly, the PBS fees’ slice of KCET’s entire net revenue pie increased from 13 percent to 25 percent. “If you went from spending 13 percent to 25 percent on any budget item in your household,” said Jerome, “you’d either say, ‘I have to have less of this,’ or ‘I need to go to the merchant and say I need a discount. You have to help me out or I can’t be a customer.’ That’s essentially what happened.” At this point PBS froze its member stations’ dues so they wouldn’t climb any higher, but KCET was left paying more than it ever had or could continue to pay.

A Public Service’s Plea

Intense negotiations between KCET and PBS began in December 2009, explained Jerome, but again they went nowhere. His station reported it could only pay $3 million a year, but wanted nothing more than to work out a solution so it could keep its membership status. Attempting, though fruitlessly, to rework a deeply entrenched paradigm, Jerome suggested the following: KCET would merge with the South Coast market’s other three PBS affiliates at the time — KOCE, KVCR, and KLCS — to create what he called the SoCal Consortium. This plan, suggested Jerome, would allow KCET to remain on board but limit its PBS programming responsibility and therefore lower its fees to a survivable level.

Before it dropped out, he explained, KCET was PBS’s primary Los Angeles-area market provider. It carried the bulk of PBS’s programming while the other three stations were only allowed to broadcast 25 percent of the prime-time lineup. Combined, the limited service threesome paid $2.1 million in dues per year. But, Jerome noted, each station was allowed to pick and choose which shows it aired, creating competition for one audience with the same programs. “KCET’s PBS brand was being eviscerated by three other stations also promoting PBS and running the same programs,” Jerome said. The affiliates would inherently pick the most popular shows, he went on, and at one point all four carried Antiques Roadshow at similar times.

KCET’s ratings for PBS programming had gone down 38 percent in prime time and 69 percent in daytime because of the overlap, Jerome claimed. The South Coast market was the only one in the country to host four PBS carriers, but there are 29 other markets in the U.S. with multiple affiliates that are reportedly experiencing versions of the same problem.

Jerome proposed merging all four stations in such a way that they would air different shows — but, combined, air PBS’s full prime-time slate — and cross-promote one another. And KCET would figure out a way to broadcast the other stations’ signals up the coast since it already had the technology to do so. “It hadn’t been done anywhere else,” said Jerome, “but there was no downside.” The Corporation for Public Broadcasting even conducted a study on the idea and deemed it workable.

And while the other station heads were reportedly game, PBS nixed the scheme: It has a rule that every market must have a primary provider. Divvying the lineup simply wasn’t an option, PBS’s management ruled. “Being fair to them, they would have had to make an exception to their policy,” said Jerome.

With the pitch for the SoCal Consortium dead in the water, and PBS not budging on its required $7 million a year in membership dues from KCET, the station was forced to make a painful decision. In May 2009, the board passed a unanimous resolution authorizing KCET to leave PBS as a full-service station and go independent. Of the move, PBS’s Anne Bentley stated in her email, “The leadership of KCET clearly believes that there is room in Los Angeles for a different type of public station, and that’s the path that they’ve embarked on.”

However, when KCET then offered to remain a limited service provider after KOCE was named the primary (Jerome said the $3 million a year KCET could afford would allow it to carry the necessary 25 percent lineup), it never got a response from PBS. “What does it say about PBS when it does not come back to us — when it doesn’t try to keep us in — and lets the second-largest dues payer in the country leave when the overall economics are the way they are?” asked Jerome. “Clearly, there is a purpose that I don’t really know.”

‘Where’s the West Coast?’

Yet Jerome theorized that the design, again, may be rooted in PBS’s seeming reluctance to change its ways and think outside the box despite a landscape of rapidly evolving public and commercial media. The vast majority of PBS’s “icon programs,” Jerome noted, are produced by three East Coast stations — WGBH in Boston, WNET in New York, and WETA in Washington. The average prime-time series has been on for 32 years, and the last major new series was implemented more than eight years ago.

“What you have here, in my opinion, is an organization that is completely adverse to change,” said Jerome. “You have a system where PBS and three producing stations in the Northeast within 200 miles of each other are virtually making all the programming decisions for public television. And I know, I just know, that in 1967, when the Public Television Act was written into law by Lyndon Johnson, he could not possibly have known that public television would be defined by 8 or tenshows that are produced by three stations. Where is the West Coast here?” he went on. “The West Coast is almost completely unrepresented.”

With that in mind, Jerome said KCET is taking its newfound independence and running with it. The station has reworked its budget and priorities to tap into Southern California’s “burgeoning cultural expansion,” investing in a community that’s the “creative capital of the country.” Expanding its coverage of local news, arts, and culture — creating a station that reports on California’s health science and medicine, education, governance, and so on — KCET wants to “translate to the people how this community is evolving so they can celebrate the things that are going on here,” Jerome said.

It’ll take a few years for KCET to completely transform itself while at the same time continue its current public broadcast services — “I call it changing the tires going 90 miles per hour,” joked Jerome — but KCET is committed to filling its shelf space with “terrific programs,” as he put it, like Hustle, The Nature of Things with David Suzuki, and MI-5, to name a few. “It’s a damn good schedule,” Jerome summed up.