Enviros Sue over Septic System Rules

Say State Agency Has Taken Too Long to Implement Regulations

Fed up with a state agency for allegedly dragging its feet as it tries to implement a set of septic system regulations, two environmental advocacy groups, including Santa Barbara’s Heal the Ocean, filed a lawsuit this week against the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). The complaint blasts the board for taking too long — over seven years too long — to adopt septic system permitting and operation standards after a bill on the matter (AB 885) was introduced by former assemblymember Hannah-Beth Jackson and signed into law in 2000. The rules were supposed to go into effect by January 1, 2004.

“The delay occurring on this issue is truly embarrassing,” said Jackson in a statement. “We were able to land a man on the moon in less time than it’s taken for the State of California to get these regulations in place.” Dr. Mark Gold of Santa Monica’s Heal the Bay, the other nonprofit involved in the suit, said, “Since the State Water Board process has failed to produce final regulations seven years after the statutory deadline, we have no other choice but to sue the Board in order to protect public health and aquatic life.”

California is one of only two states in the country that doesn’t have set ways to monitor on-site wastewater treatment systems, the discharges of which have often been proven to contain pollutants like parasites, bacteria, toxic compounds, and heavy metals. These substances, say Heal the Ocean representatives, pose real risks to human and environmental health, and thousands of systems are “improperly sited in areas of high groundwater, poor soils, or next to creeks and beaches.” There are around 1.2 million septic systems operating throughout the state — pumping 420 million gallons of wastewater per day — that serve approximately 3.4 million people or 10 percent of California’s population.

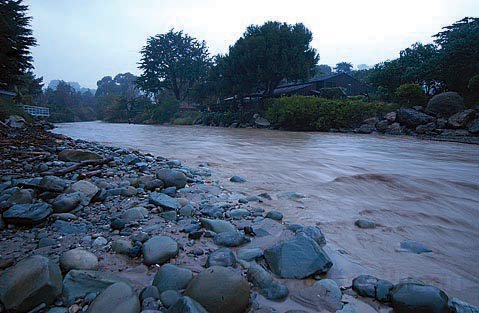

Hillary Hauser, Heal the Ocean’s executive director, pointed specifically to Rincon Point as an area of concern, noting that improperly treated discharge from a cluster of septic systems in the area has and continues to make surfers and beach-goers sick. “DNA tests conducted by our organization confirmed the presence of human waste in the Rincon Lagoon,” Hauser said in a statement. “There are many places in California where septic systems do not belong, where similar leaching occurs daily.” Rainy weather, like the kind hitting the South Coast this weekend, only exacerbates the issue, said Hauser, as pollutants are flushed from properties in higher concentrations.

The water board itself, the lawsuit charges, has acknowledged the dangers of septic systems in its own reports but inexplicably failed to act. “Groundwater pollution related to [septic systems] is occurring and action is needed to minimize future adverse effects on water quality,” the SWRCB is quoted in the complaint. “Conventional [septic systems] are often neglected and maintained only when failure has occurred or is imminent. This is due in part to the general but erroneous belief that [septic systems] require little or no maintenance.”

And the SWRCB discovered, the suit alleges, that approximately 40 percent of houses that use a septic system draw their drinking water from groundwater near discharge areas. Water board staff purportedly sampled over 1,000 domestic wells in five different counties and found that 25 percent of the wells had water quality problems.

While Heal the Ocean and Heal the Bay acknowledge that, over the years, the SWRCB has worked to comply with AB 885, it has stalled noticeably in making the final push. A draft environmental impact report was circulated for public comment from early November 2008 through February 2009, but the SWRCB allegedly failed to revise the draft regulations and then circulate the final report as promised. A spokesperson for the SWRCB wouldn’t comment on the specifics of the lawsuit but told The Independent that a final draft of septic rules is “in the works right now, and should be out some time in the next few months.” The delay up until now, he said, was par for the course as public processes always take a long time.