Undecided

Mother and Daughter Explore the Choices Provided by the Women’s Movement and the Resulting Angst Facing the Postfeminism Generation

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?” asked Alice. “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat. In their book Undecided, Barbara and Shannon Kelley start the prologue with this quote from Alice in Wonderland. It’s an apt sentiment from which to begin — the entirety of the tome explores and seeks to understand the myriad choices women have today, the decisions that must be made as a result, and the angst that it has created.

“We’d begun the day talking about a phenomenon we’d noticed again and again in women of the post-feminist generation,” the Kelleys write in explanation of how the book came about, “a general malaise with symptoms that are a combination of ‘analysis paralysis,’ ‘grass is greener’ syndrome, and a sense that there are far too many choices to deal with. It was a mystery, yet it seemed an indisputable touchstone of the zeitgeist: Women who, despite apparently having it all (good education, great job, cool place to live), are miserable. … Sure, it could be easy to dismiss these ladies as spoiled. Here they have everything their mothers had ever dreamed of. And yet, the angst is real. And universal. These are women bred for success. And seem to be miserable because of it.”

In Undecided, Shannon and Barbara look at the choices that today’s women have thanks to the success of the Women’s Movement — and the unintended consequences of having those choices. They examine the surprising flipside of messages like, “You can have it all,” and, “You can do anything,” that, while intended to be empowering, may actually do women more harm than good. They look at the science and psychology of decision making, the history of feminism, and the differences between men and women, and contextualize it all with insight from experts and the stories of hundreds of women who call themselves undecided. The following are excerpts from Undecided: How to Ditch the Endless Quest for Perfect and Find the Career — and Life —That’s Right for You.

The Road Not Traveled

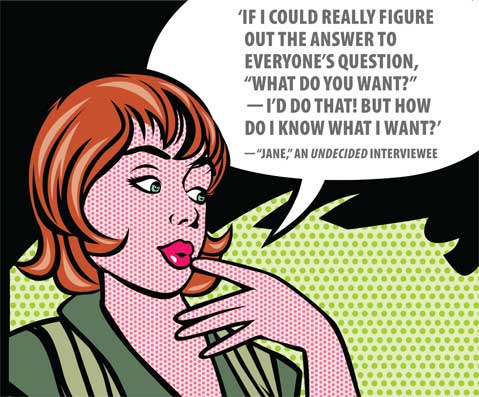

“Sometimes she thought, in a strange way, life was so much easier for people with no options …You didn’t sit around thinking, I could have been a documentarian or a forensic psychologist or a sitcom writer.”

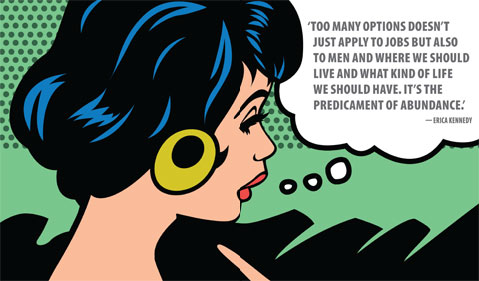

That’s a quote from Sydney, the heroine of Erica Kennedy’s novel Feminista. And it speaks to one of the more insidious side effects of a life characterized by limitless options: grass-is-greener syndrome. We’ve arrived at this epidemic honestly, on the shoulders of our foremothers’ best intentions. With its focus on creating opportunities, feminism has brought us to an expanse of open doors, but without a strategy to help us choose one. And so we frequently find ourselves obsessing over what’s going on behind each and every one.

Or, as Kennedy herself told us, “Too many options doesn’t just apply to jobs but also to men and where we should live and what kind of life we should have. It’s the predicament of abundance. As women, all these doors have been thrown open for us, but it’s like, ‘Oh no, which one do I choose and where the fuck is it going to lead me?’”

Bingo.

It’s like each of us is living a “Choose Your Own Adventure” story, but we’re incapable of focusing on whatever adventure we’ve chosen. Instead — like the kid who can’t resist flipping back to see how the other adventures might have panned out — we angst over the adventures we didn’t choose, and it’s an angst that’s made all the more intense having been weaned on the notion that we can have it all. And, as opposed to the women we met in the last chapter (who are in their early twenties and still pretty driven to have that high-echelon “all” they believe is their due), the women we’ll meet here — who have only a few more years under their belts — are angsty over the ever-increasing realization that they probably can’t have it all. Which is not only a bummer, but also adds a certain time-crunch to the angst.

Chloe’s story cuts to the chase: “I was walking home from work, having a low self-esteem day, and I saw this sign in a storefront. It was of three smiling women, around my age, and I just thought to myself, I bet they all have kids.”

Chloe doesn’t even want to have children — an assertion she reiterated before admitting that, nevertheless, it didn’t stop her tears. “I just feel like life is passing me by.”

For the record, Chloe is amazing and enviable in her own right: She’s lived and worked everywhere from New York City to Brazil, Mexico to Southern California, and she is successful, beautiful, talented, and happily married. But those things never seem to matter much when we’re confronted with the green-grassed monster; when we catch a glimpse of the place where that road we opted not to travel may have led.

Julie, a reader of our blog, told us her story, too — and in its way, it’s quite similar to Chloe’s.

Here’s some of what she wrote: “I am a thirty-year-old mother of two who has definitely suffered from the grass-is-greener syndrome. After my daughter was born, I chose to stay at home with my children while pursuing an education. I not only became extremely depressed, because I felt that I should be ‘doing it all’ (work, school, housewifing, and mothering), but I perceived criticism from other women for my choice. I felt like I was worthless. I did not appreciate my life and the wonderful opportunity that I had to be with my children. I was more concerned with what I thought I should be doing than with what I had chosen to do. I felt that there was something wrong with me, because I could not be the supermom that is portrayed on television as the epitome of womanhood. When I finally decided that I needed a job, I spent the whole time I was at work wishing I was at home with my kids.”

And then there’s Sam, who’s excelled at her job as an account manager at an advertising agency — even while she spends a fair chunk of her billable hours plotting last-minute vacays to Berlin and volunteer trips to Haiti and daydreaming about the road not traveled: “I majored in theater in college, only to burn out on it and give it up after college. But now, every day, I think about that life, the performance life … and I wonder what I’m missing. What did I give up? Would I be happier if I had just stuck with it? Oy, it drives me mad, and I keep hoping that maybe all of my going-around about it will make me so nauseated I’ll actually get sick (of myself) and do something. Hasn’t happened yet.”

They’re familiar feelings, even for those of us who outwardly do seem to have it all. And yet, for women, the whole “life is passing me by” thing is relatively new. (For men, the story’s so old, there’s an archetype: divorce, young girlfriend, Corvette. Even, for some, toupee. Cringe.) Aging, of course, is as old as time, but this particular brand of angst has less to do with aging per se than it does with the idea that, as time goes by, what once looked like a wide-open wonderland, bursting with possibilities and open doors, starts looking more and more like a collage of What You’re Missing Out On. That with every choice we make, we shut those other doors for good — one by painful one. It’s an evil little phenomenon economists call “opportunity cost”: when picking one thing means we can’t have the others. And there’s no model for how to deal with our feelings over what we’re leaving behind Doors No. 2 through Infinity (after all, if we can do anything, the possibilities are literally infinite, right?). This bounty of opportunity is so new that we were sent off to conquer it with no tools — just an admonishment that we’d best make the most of it: You’re so lucky!

We know we’re blessed to have all these options. We get it. And so is it any wonder we want a shot at each and every one of them?

But therein lies the rub.

We want to travel but can’t take time off whenever we feel like it if we’re also trying to get our business off the ground — and featured on Oprah. We want a family, but that’d mean that packing up and moving to Cairo or New Orleans on a whim is pretty much off the table. We want to be there for our daughter’s every milestone, yet we also want to model what a “successful career woman” looks like. We want torrid affairs and hot sex, but where would that leave our husbands? We want financial security and a latte on our way to the office every morning, but we sit in our ergonomically correct chairs daydreaming about trekking through Cambodia with nothing but our camera and a mosquito net. We want to be an artist, but have gotten rather used to that roof over our heads. We want to be ourselves, fully and completely, but would like to fit in at cocktail parties, too. (And when on earth are we going to find the time to write that novel?)

Chasing the Mirage

A recent study on social networking found that sites like Facebook provide the perfect environment for managing the presentation of self — commenting and sharing obsessively, all with an eye toward self-promotion. And in most cases, the researchers found, these carefully cultivated online identities were not always in sync with real-world personalities. “Online environments enable individuals to engage in a controlled setting where an ideal identity can be conveyed,” the authors wrote. “[They] provide an ideal environment for the expression of the ‘hoped-for possible self,’ a subgroup of the possible self. This state emphasizes realistic socially desirable identities an individual would like to establish, given the right circumstances.”

Marketing folks might say we’re branding ourselves in our profile pictures, our status updates, or our tweets. We say that maybe we’re feeding the iconic self, the self-image we’ve constructed which, in ways big and small, is the face of our great expectations. She’s kind of a tyrant, too.

For many of us, this self that we’ve cultivated is worked out in detail, with little tolerance for deviation. Swarthmore’s Barry Schwartz tells us that while he hasn’t specifically looked into the ways in which the iconic self can influence our choices, “it doesn’t shock me if that’s true,” he says. “What I will say, which may be relevant to this notion, is this: Nowadays, everything counts as a marker of who you are in a way that wasn’t true when there were fewer options. So just to give you one example: When all you could buy were Lee’s or Levi’s, then your jeans didn’t tell the world anything about who you were, because there was a huge variation in people, but there were only two kinds of jeans, you know? When there are two thousand kinds of jeans, now all of a sudden, you are what you wear…What this means is that [with] every decision, the stakes have gone up. It’s not just about jeans that fit; it’s about jeans that convey a certain image to the world of what kind of person you are. And if you see it that way, it’s not so shocking that people put so much time and effort into what seem like trivial decisions. Because they’re not trivial anymore.”

Conversations with the Road Warriors

Here comes some wisdom, (from Daria Todor, an Employment Assistance Counselor, career coach, and psychotherapist who has dealt with thousands of women in the workplace for the past 20 years). “Every decision entails trade-off, and it entails commitment,” she says. “And with that comes the sense of grief and loss. You make a commitment to one thing, you are by definition turning your back on other options. Not knowing how to grieve a loss is really powerful. And I believe that a lot of what shows up in a therapist’s office as depression may be a form of this grieving that is a natural part of growing up. And so there’s an avoidance of making a decision because of the pain threshold.”

Ramani Durvasula, PhD — a clinical psychologist, professor of psychology, and director of the psychology clinic and clinical-training program at California State University Los Angeles — deals with a student population that is predominantly minority women, many with kids. She’s advised hundreds of them on career choices, and what she tells them is that the concept of choice is one tricky, slippery slope. “The agenda is still loud and clear: ‘You can have it all.’ My advice to all of the students is, ‘No, you cannot.’ So often, the discourse about choice is what you are choosing,” she told us. “We leave out the rather unpalatable piece about ‘What do you give up?’”

She offers herself up as case study. “I’m a single mother; I went through a divorce; I’m Indian; my family wanted nothing further to do with me — so it wasn’t just divorcing my husband, but literally I lost my life.” She went into debt, had to find a new home for herself and her two daughters. She’s working three jobs. And what she tells the young women she counsels is to think like a man who will someday be responsible for supporting a family and paying a mortgage. “And some of these girls just stare at me wide-eyed, because they never thought about this. Some look at me and say, ‘I want to be a doctor,’ and I say, ‘Okay, four years of college, four years of med school, four to six years of residency … ’ And they’re like, ‘When do the kids come in?’ and I say, ‘The kids can come in, but something’s got to give. It may be that you make a sacrifice in the arena of marriage. It may be that you don’t have the 24/7 you want with your child.’”

Her point: The idea of having it all, of unlimited options, is a fantasy, and a dangerous one at that. “What women have to do is rule things out. We need to be more tolerant of giving women a vocabulary of taking chances. I think men are much better at taking chances, and I think men have a better feel for time. Women hear the biological clock ticking a hell of a lot earlier than they need to. The painful part is: This is not easy. What I want to communicate to young women is, ‘You can try many of these things, but there are going to be challenges. If you think you’re going to be able to screw your husband, raise your kids, clean your house, and go to work, you’re mistaken. You’re going to have a messy house, an unscrewed husband, kids you’re not always with, and a job you can’t always do.’”

It’s all about the risks, she says, the willingness to make mistakes. “I always say to my students, ‘You’ll get over a failure, but you will never recover from regret. That’s not recoverable. Go ahead and try a job you might fail at. Go ahead and take some chances.’ Because where these women often get frustrated is with the paths not taken. And what I tell them is that I want them to try a lot of things — and then report back. And that’s frightening, because they still feel very programmed: They want the marriage, the house, the kids, the job — but have absolutely no sense how to get all those things at the same time. And I just don’t think it’s gettable in a single package. Women need to live lives where they’re willing to rule things out. Like I ruled out marriage. But I had to do it to rule it out. What ends up happening is that if you don’t have the realization, you wonder.”

It all becomes more problematic with the career options women have now as compared to a generation ago, Durvasula says. “When certain paths were never even possible, it obviates people from responsibility, right? While to me that’s its own form of a prison, it’s also its own form of freedom if you couldn’t even entertain the option. So I think that can speak to the dissatisfaction you see in young women: You now have to take responsibility. If you screw it up, it’s your screwup. You can’t blame somebody else.”