Braving Burning Busses and Brutal Beatings

Santa Barbara Freedom Rider to Appear on Oprah.

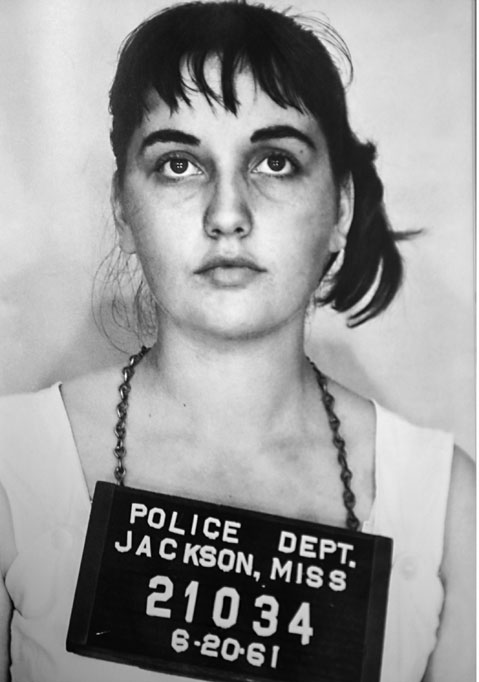

It was 50 years ago when Jorgia Bordofsky spent 40 days locked up in the maximum-security wing of Mississippi’s notorious Parchman penitentiary for the crime of premeditatedly traveling on a train with black people. Young, beautiful, and outraged, Bordofsky — then 19 — was one of 450 Freedom Riders to be arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, in the summer of 1961. This week, Bordofsky, now a longtime Santa Barbara resident and health-care professional, was one of 180 Freedom Riders to be invited to appear on The Oprah Winfrey Show to recount her experiences. “Things have changed a lot since then,” she said. “I don’t need my 15 minutes of fame; people have to understand things can change.”

Back then, Bordofsky — then Jorgia Siegel — was attending UC Berkeley when she heard a speaker describe the violence unfolding in the Southern United States when black and white Freedom Riders attempted to integrate the interstate highways by riding Greyhound and Trailways buses, then rigidly segregated, together. In some cases, the buses were lit on fire or bombed. In others, their tires were slashed, and the offending passengers violently attacked by angry Southern whites seeking to uphold segregation. Bordofsky, who grew up in what would later become Watts, was horrified. “This is what’s going on in my country?” she asked. “People will beat you up and kill you because you’re in an integrated group?” The daughter of Jewish progressives, Bordofsky remembers her high school being integrated. But she also remembers a cross being burned in her neighborhood, accompanied by warning signs that read “No Jews or Colored After Dark.” When the speaker she heard at Berkeley described a campaign then underway to overwhelm the jail cells of the south with nonviolent protestors, Bordofsky stepped up. “Part of it was from being Jewish,” she said. “That’s an important part; we didn’t want to be like the Germans before World War II.”

She hopped a train from Los Angeles to New Orleans, where she and about 400 others were trained in the techniques of nonviolent resistance. During her time there, she was put up in the home of movement supporters. At New Orleans on June 20, 1961, she and 13 others — three blacks, 11 whites, five women and nine men — took a train to Jackson. The police were waiting when the train arrived. “Someone said, ‘You all move on out,’ and we didn’t move. So they threw us in the paddy wagon and that was the end of it.”

Not exactly. From there, Bordofsky was taken to the first of three jails she would be confined in. Initially, she was mistaken for “a mulatto” because of her tan and placed in a cell with black women. When the jailers recognized their mistake, they placed her in another cell that held about 25 people. There was one toilet in the corner. If you had to go, you went in front of everyone. Mattresses were caked in blood and urine. Then she was transferred to the Parchman Farm penitentiary, where she was given a black-and-white prison smock and placed in the maximum-security wing adjacent to Death Row. There, she would serve out the rest of her sentence, sharing a cell with two other women. But other Freedom Riders were on the same wing. One, a Greek history professor, gave daily lectures. Bordofsky said she learned how to make chess pieces out of bread dough and fashion makeshift playing cards out of toilet paper. Lights were kept on 24 hours a day. The guards clanged on the bars every three hours. To entertain herself, Bordofsky sang Broadway showtunes. “All of them,” she said. “What else are you going to do?”

After her 40 days, Bordofsky was released. Her bail money was raised by others in the movement. She would have to come back two more times for court appearances. “They were trying to bankrupt the movement by making us come back and forth so many times,” she said. The experience was not pleasant, but Bordofsky was not beaten or mistreated. “I knew I wasn’t going to live there the rest of my life,” she said. “That’s not the same for the people I met who lived there. They lost their jobs; their parents lost their jobs; they were kicked out of school.”

After her release, Bordofsky signed up to speak about her experiences, raise money, and recruit other Freedom Riders. “Wherever they told me to go, I went,” she said. One time, though, she asked to be dispatched to New York, where she met her husband, now a CPA. “Lo and behold, four children later, I live here in Santa Barbara,” she said.

Two years ago, Bordofsky was one of hundreds of Freedom Riders whose booking photos were featured in the powerful photojournalism book Breach of Peace. A year later, PBS produced a two-hour documentary on the Freedom Riders, which will air May 16. About a year ago, Oprah Winfrey saw a preview of that film. She was moved to track down a number of the 450 arrested in Jackson that summer and invite them on her show. “If I tell people about the rides, they’re polite, but if I say I’m going on Oprah, people say, ‘You’re going on Oprah?!’”

Who would have thought 50 years ago that a black man would be in the White House and that a black woman would be one of the most powerful celebrities on TV? In the meantime, Bordofsky is content to savor her 15 minutes of shared fame. “It’s all about showing that people can make a change, that people can change,” she said. “And maybe we can do it again.”