The Company That Cuts Both Ways

Vector Marketing, Seller of Cutco Knives, Tries to Shed its Reputation as Employment Scam

On a late afternoon in June, seven dressed up 18- and 19-year-olds sat nervously in an unadorned waiting room on upper State Street. A few of them filled out paperwork, but most were glued to their cell phones. No one spoke.

The students — many of whom had graduated from high school just weeks before — were waiting to be interviewed by Vector Marketing, a company that had enticed them with flyers advertising some undefined “Work for Students.”

In the interview, the students would learn that Vector Marketing contracts independent sales representatives — typically recent high school graduates like themselves — to work part-time over the summer selling upscale knives and kitchen accessories. Sales representatives are hired throughout the year, but summer is Vector’s crunch time to recruit new reps.

While some of the students — suspicious of a scam — will leave the interview and continue their summer job search in more traditional venues, several of them will take the position. But only some of these representatives will stay with the company long enough to build up a profitable client base.

As Vector Marketing braces for a pending $13 million California class action settlement that will be finalized in the next few weeks, the company is making a national push to shed its negative image. Meanwhile, the Santa Barbara community remains divided on the company. While some workers and customers praise Vector for offering valuable work experience to students right out of high school, others accuse the company of using overly aggressive recruiting tactics and preying on desperate, naive students.

The Sales Business

Founded in 1981, Vector Marketing is the sales arm of New York-based Cutco Cutlery, which manufactures knives and kitchen products for Vector representatives to distribute. Nationwide, Vector has over 200 offices and contracts 60,000 student workers annually, the majority of whom are recruited for entry level sales representative positions over the summer.

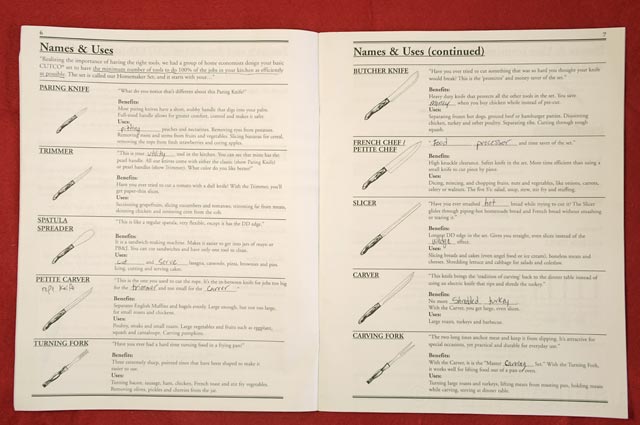

Vector reps — who are technically independent contractors, not employees — first undergo a three-day unpaid training process in which they learn and practice demonstrations with the knives they will be selling. After completing training, sales representatives are instructed to call friends and family — who must be over 25 and working full time — to set an hour-long appointment to come to their homes and demonstrate Cutco products. From this initial appointment, the company hopes that sales representatives can build a client base from a network of referrals.

Armed with rope, pennies, and leather, the sales representatives demonstrate their knives on these and any other available fruits or vegetables as they try to make a sale. Sales representatives earn a commission of between 10 and 30 percent for every successful sale and $16 for every unsuccessful appointment. According to the company, new sales representatives make a sale in approximately 60 percent of appointments, while more experienced workers can make a sale up to 70 percent of the time. Sales representatives set their own appointments, and can work as frequently or infrequently as they wish.

But up until February of this year, there was a catch. New sales representatives were required to make a $135 safety deposit before they were given a demonstration kit to use during appointments. For newly hired students — many of whom had never held a real job before — the deposit marked a significant financial burden. Although Vector guarantees a refund of the safety deposit for sales representatives who leave the company, the required upfront payment has contributed to its dubious reputation.

A Troubled History

Over the years, multiple ex-sales representatives have sued Vector — a Better Business Bureau-accredited corporation — for alleged violations of state and federal labor laws. In 1990, the Arizona Attorney General sued Vector for alleged deceptive recruiting techniques. After seven years of legal proceedings, the case was resolved in a settlement, which required Vector to reform its advertising of its compensation system in Arizona. In 1994, the state of Wisconsin ordered Vector to refrain from deceptive recruiting practices, leading the company to temporarily stop recruiting in the state.

Another ex-sales representative who appealed to the New York Department of Labor to win compensation for unpaid training cofounded an online group called SAVE (Students Against Vector Exploitation). Their Yahoo group — which has over 1,100 members — holds monthly chat room meetings “to expose the unethical and scandalous nature of this company,” according to the group’s Web site.

In 2008, Vector was confronted with its most serious legal challenge yet when Alicia Harris — a former sales representative at Vector’s Pasadena office — sued Vector in a class action lawsuit for allegedly violating California labor laws. Harris’s lawyer Stanley Saltzman argued that the company’s three-day unpaid training period violated California minimum wage law and that Vector required sales representatives to “purchase” their demonstration kits.

“The term [‘security deposit’] was just a disguise,” said Saltzman. “Sales reps shouldn’t have had to pay for [the demonstration kit] upfront.”

While Vector argued that the $135 demonstration kit fee was a returnable security deposit, Saltzman cited data that suggested that over 90 percent of Vector sales representatives in California do not pursue or otherwise receive a refund from the company upon leaving the company. To avoid further litigation, Vector agreed to a settlement earlier this year, which would require them to pay a total of $13 million to be distributed among California sales representatives who worked for the company between October 15, 2004, and April 6, 2011. The settlement is still pending final approval in court on August 10.

For its part, Vector is “looking at how we might address the concerns this case raised,” according to Sarah Baker Andrus, who is Vector’s director of External Relations and Academic Programs.

One of these concerns may have already been addressed. In the midst of litigation over the $13 million settlement, Vector made a corporation-wide decision to remove the controversial security deposit fee for a new demonstration kit. Their workers may now borrow a demonstration kit from the company at no charge.

Despite coming in concert with the costly lawsuit, the decision was made to expand opportunity for potential sales representatives, said Andrus. “By saying we no longer collected that deposit, somebody who perhaps was on the fence about the opportunity or didn’t understand or might have been uncomfortable now has a much easier decision,” she said.

Now in its first summer after revoking the controversial fee, Vector Marketing stands poised to redefine its role in the Santa Barbara community.

A Campus Presence

Vector Marketing established its Santa Barbara office at 3887 State Street #208 in May 2006. The Santa Barbara branch has steadily grown in its five years of existence.

By June 20 of this year, Vector had already interviewed 160 applicants for its sales representative positions in Santa Barbara. Only 18 of these applicants joined the company.

To recruit its large applicant pool, Vector maintains a visible presence on college campuses in Santa Barbara. Advertising “work for students,” recruiters use tabling, job fairs, flyers, posters, and chalkboard postings to spread the word at UCSB and SBCC. They also use a direct mailing company to send a recruiting letter to every recent public high school graduate in Santa Barbara at the beginning of the summer.

Although Monica Israel — Vector’s Santa Barbara branch manager — said that all Vector recruiting tactics are in compliance with campus career centers, an SBCC employee said this is not the case.

The employee — who requested anonymity to limit her involvement with Vector — said that Vector recruiters come into SBCC classrooms without permission to post chalkboard advertisements. When confronted by lecturers, the recruiters say untruthfully that they are affiliated with the SBCC Career Center, according to the employee.

“I’ve had a lot of frustration with them,” she said. “The reps are just pushy and willing to lie about anything to recruit our students.”

She added that during her 10 years at SBCC, Vector recruiters are “the number one most-complained-about troublemakers.”

Israel denied the allegations against her recruiters, emphasizing that the alleged deceitful practice is against company policy.

A Disappointing Experience

At the beginning of last summer, Lauren Jackson — who was 18 at the time — stumbled across an advertisement for “Work for Students” while on her Facebook account. She had just graduated from Santa Barbara High School days before, and was looking for summer work before beginning her college career at SBCC in the fall.

Although she was uncertain as to what kind of work she was applying for, Jackson called the number listed in the advertisement to schedule an interview.

Jackson was quickly hired and began her training, where she said she learned valuable skills about salesmanship. But when she was instructed to put down a $135 security deposit for a demonstration kit, she began to question Vector’s legitimacy.

“It’s just not fair,” she said. “You’re trying to get a job to make money and they’re asking you to spend probably more than what you have at the time.”

Jackson’s doubts intensified further when she was instructed to call family and friends to set up her first client appointment.

“I thought it was a rip-off,” she said. “You’re basically trying to sell something to your family.”

Jackson set up an appointment with a family friend and made her first sale, earning about $16 in commission. But after researching lawsuits filed against Vector with her father, Jackson decided to quit the company.

Although she was given instructions about how to return her demonstration kit for a refund of the security deposit, she decided to keep the demonstration products, which were “actually pretty good knives.”

Though she had the option to break even, Jackson left the company about $120 poorer than she had been upon joining.

A Rewarding College Job

But not all Santa Barbara students have lost money while working for Vector. Eighteen-year-old Michelle Dang is a Vector success story, earning about $500 a month since joining the company this past April.

But Dang — who uses her Vector earnings to help fund her education at SBCC and UCSB — said she understands why Vector has a bad reputation.

“The way they do things is kind of sketchy,” she admitted. “It may seem like a scam, but it’s actually really legit.”

Dang — who spent much of the past school year searching for a part-time job — had eliminated Vector Marketing as a potential employer after hearing rumors from friends that the company was a scam.

But when she was given a flyer on campus advertising “work for students” (and omitting the company name), she decided to pursue the position.

“I had no idea what it was until I walked into the office for my interview,” she said, recalling her surprise when she realized she had walked into the Vector office.

Although she thought that Vector was “weird” after learning about the company’s door-to-door sales techniques in her interview, she decided to give the job a try.

She said she became a convert after earning $63 in commission in a sale during her first appointment with her friend’s mother. “At that point I was pretty impressed,” she said. “Once they started direct depositing, I knew it was real.”

And since making her first sale, Dang said she has been completely satisfied with her job at Vector. “It’s good money and it teaches you a lot about the business world,” she gushed. “I’m so glad it didn’t turn out to be a scam.”

But Dang admitted that had the $135 security deposit still been in place when she had started at the company, she would not have taken the job. She said that while demonstration kits are still available for purchase for sales representatives who do not want to have to check the loaner kit in and out of the office, she has never felt any pressure from the company to buy one.

As Vector moves forward from its scandal-ridden past, it is relying on poster children like Dang to prove that the company is a legitimate, profitable job for students. But only time will tell if Dang and others like her are the norm or the exception.