Teaching Our Children Well

Learning to Ride

Where did you learn to ride? Most of us learned to ride bikes as young children. I learned on Bentley Road in Cedar Grove, New Jersey. The street was flat for the first five blocks and then headed downhill. I can still remember the first few uncertain blocks, my dad holding onto the seat, running behind me and repeating over and over “Pedal!” When he let go, I wobbled forward under my own power as he alternated yelling “Pedal!” with “Steer!” That was good enough till the hill. I didn’t wear a bike helmet, and there were certainly no classes for kids to learn how to bike. That’s why you had parents.

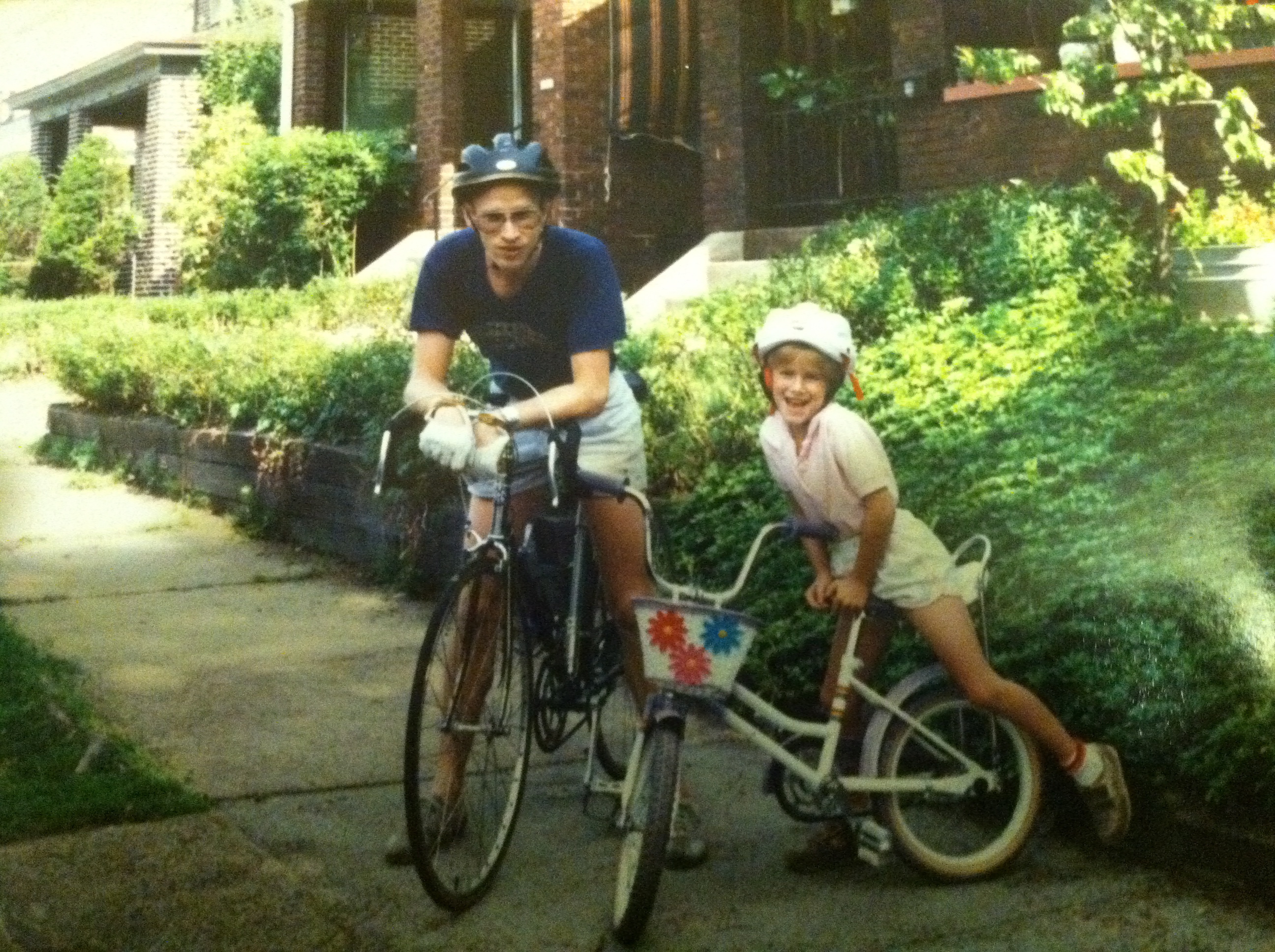

Years later in Pittsburgh, PA, my daughter, Danielle, learned how to ride a bike with my help. There were still no classes, but she did wear a helmet, as did I. Here’s the proof.

Danielle is now 31 years old and works professionally for the City of Portland doing active transportation education and outreach. She also rides for Team Beer. Who says early experiences don’t matter?

We’re fortunate youth bike education has come a long way. Santa Barbara has some excellent programs. I recently rode with a group of students from La Colina Junior High School. They are enrolled in a six-week after-school program run by Bici Centro, a project of the Santa Barbara Bicycle Coalition. It’s called Pedal Power. Below is a group photo.

On two recent bike rides with these seventh graders from La Colina, I watched as they demonstrated their street skills. They rode a mix of mountain and BMX bicycles and had mastered signaling left- and right-hand turns. They moved into the correct traffic lane for turns and were scanning for traffic from the front, sides, and rear. As we rode in the bike lane along the heavily traveled Calle Real, you could see their growing sense of self-confidence. Even more importantly, they were learning to work and ride together as a group. They were communicating with each other about road hazards, riding together in a line, waiting for slower riders, maintaining distance and speed. More experienced riders were helping learners master new skills. Their instructors, Elisa and Amy, were giving them encouragement and teaching them street smarts the whole way. They were learning life lessons of responsibility, pride, and independence — not always easy lessons for 12-year-olds.

Pedal Power also teaches basic wrenching skills so that kids can learn to take care of simple maintenance tasks like putting air in tires, fixing flats, or adjusting the brakes on their bikes. These are basic skills that build self-reliance and offer both manual and intellectual challenges. Conquering those challenges helps children become more confident. A couple years ago at La Cumbre Jr. High, one young girl, challenged by school, graduated after six weeks with a huge smile on her face, never having missed a session, and was by far the best mechanic in the group.

Learning to fix your bike is not just about getting your hands dirty and greasy, although that is very important. Taking a tire off a wheel, putting a patch on a tube, tightening a brake cable, or oiling a chain are only the mechanical facets of the challenge. The hardest task can be figuring out what the real problem is. That often requires the problem-solving skills of Sherlock Holmes or Nancy Drew. A flat tire could be: a nail puncture in the tube, a problem with the valve, a spoke-end rubbing, or maybe one of your friends playing a trick on you by letting all the air out. Thinking comes before getting your hands dirty. That is another important lesson.

Before we headed out on our rides, everyone did an ABC Quick Check on their bikes. “A” is for air in the tires, “B” is for brakes that work, and “C” is for chain, cogs, and cranks. That’s a good check for all riders. When you’re swooping down the hill at full speed, you want to be sure that the friction of brake pads on rims will stop you. That’s physics. Wow, Pedal Power is also about learning some practical hands-on academics.

Many of the seventh graders at La Colina had their own bikes. For those who didn’t, no problem! They have the chance to earn a mountain bike refurbished by Bici Centro at the completion of the program. Not free. They earned it by learning to fix their bikes. They also get a bike lock, light, and an all-important helmet. They don’t always want to wear them. At 12, appearances are important, and — honestly — a helmet can look dorky.

When I ran an early childhood center in Pittsburgh, we used to insist that all children wear bike helmets while riding on the playground or gym. Many of the educators thought the requirement absurd. Sure, in my mind, there was a legal consideration. But my goal was to build a connection in even a 2-year-old’s mind between a Big Wheel and a helmet. When you get on a bike, you put a helmet on your head. Many of them rode with their helmet falling down over their eyes or pushed back or even backward at times. It didn’t matter to me; the helmet was on their head. Bike = helmet!

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about grammar. That’s odd because, if you know me, you know that my two academic anti-epiphanies were grammar and algebra. In fourth grade, I could not understand why, all of a sudden, we were taking words and phrases and diagramming them on lines that looked like streets. And, in eighth grade, I failed to comprehend why letters (x, y, a, b, etc.) were now mixed up with numbers in equations. But here I am once again pondering grammar and the imperfect tense. I used to believe that all my dreams would come true. Maybe it’s a part of getting older — the part where you realize that all your wishes may not happen but that you can enable the dreams of others. Pedal Power is about making kids’ dreams come true.

By helping our children as they learn to ride a bike, we are looking forward to where our wheels will roll. We’re giving back. When I help my daughter wobble down the street or ride with seventh graders from La Colina, I’m thanking my father for the time he spent running behind me, out of breath on cool, sunny, fall days when I was young.

My stepdaughter, Maggie, is the only one of my three kids who never learned to ride a bike. Danielle, if you remember, rides for work and pleasure. My other stepdaughter, Liv, this summer conquered the Durango to Silverton Iron Horse ride! At 24, Maggie wants to learn, and I’ve promised her that, when I’m next in Pittsburgh, I’ll help her. I can make her dream come true. She used to think that she couldn’t cycle. I know she can, and I’ll be running along behind her yelling “Pedal!” and “Steer!” as she wobbles down the street.