Cap Pensions, Don’t Destroy Them

State Retirees Get an Average of $26,000 per Year

The ultra-conservative, hyper-libertarian, anti-middle class other newspaper in our town hammers its readers with anti-public pension and anti-union rhetoric every day. We need some balance and some pension facts from another point of view. The reactionary views come from none other than the News-Press, a once-proud daily which has lost 16,000 subscriptions and all of its glory from the Tom Storke days. I have lived since 1986 on Santa Barbara’s Westside, not in Hope Ranch, or Montecito, or a gated community insulated from the mundane world of real Santa Barbara – which is certainly not one of California’s wealthiest cities, despite its glamorous reputation – and I happen to know that many retired older folks live in our community who are on one or another of our many California public pensions.

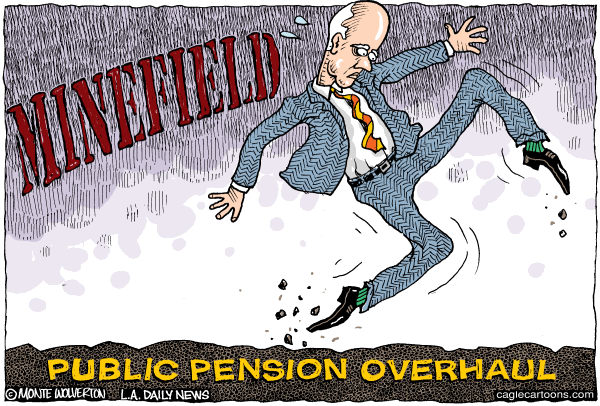

Public pensions should not be an issue connected to our state budget woes, as George Skelton has written, but it inevitably comes up as such in politics. One hears again and again, and from otherwise staunch liberals, too, that public pensions in California are a terrible budget problem. Close to 70 percent of Californians think that our public employees should pay more for their own retirement.

Yet it is quite clear that draconian cuts to public pensions will not even begin to solve the state’s budget catastrophe or Santa Barbara’s budget woes. The state’s payments for its public employees’ retirement pensions take up just 3% of the state’s budget; the average in the rest of the USA is 3.8%. And changing the public pensions offered to new hires will not help the state’s budget for several years.

I understand that the state certainly has dire budget problems, and also that the cities and counties have mounting problems with their 85 separate public pension plans. Santa Barbara County, for example, has an unfunded liability of $2.2 billion in its pension plan. We just read the terrible news that the Santa Barbara Unified School District may have to cut 70 more teachers, and this is on top of earlier massive cuts from Sacramento. This is indeed a tragedy. Still, it’s a huge mistake to tether the bigger state budget catastrophe to onerous public pension issues. We are under-taxed in this state, and the wealthy 1% like publisher McCaw would like to pit school monies against public pension payouts – but this is simply more of the class warfare couched between the lines of her daily publication (including the tendentious rants of Lanny Ebenstein and Terry Tyler).

Some significant pension reforms are needed in California in order to keep the system solvent. We all acknowledge this. But the public is generally unaware that the unions and the public pensions systems have already made significant reforms that will save money. For example, a few years ago the UC Retirement System reinstituted employer contributions to the employees’ pension fund, and last year UC increased the required employee direct-contribution as well (it will end up being between 5% and 9%). UCSB is the biggest single employer in Santa Barbara County, and many UC retirees live here. (Disclosure: Since I work in the non-profit sector I don’t qualify for a public pension, but my spouse has worked 27 years at UCSB and will qualify.)

Governor Brown’s interesting 12-point pension reform plan has riled up as many Democrats and liberals as it has conservatives, and, amazingly, has been recently supported by California’s Republicans in the legislature. [Undeclared potential candidate] Mike Stoker is on board with the governor’s ideas — where are you on this, Assemblymember Das Williams? Candidate Hannah-Beth Jackson? U.S. Rep. Lois Capps?

In studying Brown’s reform ideas it is easier to work with the simpler eight-point plan he offers on his website. In summary, Brown wants to stop pension spiking, renegotiate retirement benefit amounts for new employees (a continuation of sacrifice the young we see throughout this Recession), increase employee and local government direct contributions to retirement funds, prohibit placement agents, and establish independent oversight of public pension funds. These are persuasive and meaningful changes that will refortify the pension system if they are passed.

While we read about the luridly over-compensating public pensions of the few who gamed the pension system to the max – like the City of San Diego’s assistant water department director getting $214,000 per year – less than 2% of California public pensioners receive more than $100,000 a year. Sure, let’s cut at the top; cap the pensions of the con artists. More typical, though, is that special education teacher’s assistant of 25 years getting $9,600 per year when she retires, or the fact that the state employees’ average pension is $26,000 per year.

That number is weighted down by many elderly pensioners on very small pensions. And the 2% pensioners making more $100,000 a year, over 12,000 of them, skew that $26,000 figure upward, as well. But just for the sake of argument taking the average as actually typical, can you even imagine living well in Santa Barbara on $26,000 a year? That $26,000 is taxed, of course, in several ways. Unless the pensioner owns her house, or receives another pension such as Social Security, or via a private 401(k), or a magical gift from Mammon (you win the lottery) — suffice it to say it will be difficult to make it on this single state pension.

Both the City and County of Santa Barbara do have under-funded public pensions, just like the rest of California’s local governments, and Mayor Schneider’s reform plans for the City of Santa Barbara make good sense. Yet do not make the mistake of thinking that local governments’ financial issues will be solved by slashing pension benefits. (And please note that Brown’s plan does not call for current pensioners to accept reductions since there are strong state laws against allowing the legislature to reduce existing public pension benefits; this is about sanctity of contracts.) California retirees also toss $26 billion a year into the state’s economy, and who would want to mess with that contribution to general prosperity?

Many Americans want a clearing-out of the uppermost tiers of business, and the corrupt Congress, and “bureaucracy” everywhere — let’s “cut at the top” and, using the initiative process, cap state retirees at $100,000 per year maximum; and redistribute the monies saved back into the base of the system to preserve it. As we have criticized the feral 1%, so we have to reduce the resources of this greedy 2% — pity the billionaire pensioners no more. Yes, there will be significant legal obstacles to such a radical cap, but it will help save the entire system.

At the next election voters will have the chance to vote on pension reform propositions, but we need to scrutinize them very carefully to find a cap that reforms and strengthens public pensions, not ones that gut them and the unions supporting them.