Westside Boys & Girls Club Fights to Keep Lights On

Successful Countywide Clubs Program Short of Cash

If success were the only measure that mattered, Magda Arroyo would be sitting pretty. Since taking charge of the Westside Boys & Girls Club, which serves Santa Barbara’s most densely populated, impoverished neighborhoods, nearly two years ago, Arroyo has worked miracles. She has transformed the club into a veritable popcorn popper of rambunctious youthful activity. The number of kids has increased five-fold, and the number of programs — such as Zumba, tae kwon do, basketball, after-school tutoring, and computer classes — has skyrocketed. And then there is the Note for Notes program, which has installed a professional recording studio in the club, equipped with drums, keyboards, and a quiver of electric guitars. Arroyo has worked actively with city police and with gang members themselves to assure parents that their kids will be safe, despite the club’s proximity to Bohnett Park — often considered “ground zero” for Westside gang activity. Her efforts have apparently paid off. Gang activity at Bohnett Park is decidedly down — admittedly for a host of reasons — and parental participation at the club is decidedly up.

But success is not enough, and United Boys & Girls Clubs of Santa Barbara — the umbrella nonprofit agency through which Arroyo operates the Westside club — is on the ropes financially. As of February 19, its boardmembers were notified that United Santa Barbara — which runs the four clubs from Carpinteria to Lompoc (except the downtown facility across Canon Perdido Street from Santa Barbara High School) — cannot make its March payroll without an emergency infusion of $100,000. Since 2006, donations to the clubs have dropped off by $800,000. This reflects two new realities. First, philanthropic foundations took it in the shorts during the stock-market crash and have less money to give. What money they do have is being strategically concentrated on high-impact initiatives. In this new philanthropic world, ongoing programs — such as the Boys & Girls Clubs — are having a tough time competing.

Recently, rumors began to spread that the Westside club might have to turn off its lights completely by March 15. The good news, according to Arroyo and United’s CEO Mike Rattray, is that won’t happen; they simply won’t let it. But the bad news is that the dimmer switch might have to be dramatically lowered. Each club, including Westside, could soon experience a 12-percent cut in program funding, coupled with a 10-percent reduction in employee pay, suggestions made last week at its board’s finance committee. Of all the clubs, the Westside would be most devastated by such cuts. While its needs are the most pressing, its ability to generate revenue is the most limited. To put the Westside — and the other three Boys & Girls Clubs making up Santa Barbara United — on more stable financial footing, the board has embarked upon an aggressive fundraising campaign and will be asking the community for help. The goal is to generate $300,000 during the next 60 days. Of that, $75,000 is expected to come from the Westside club’s community.

Bootstraps and Helping Hands

In many ways, Arroyo herself personifies the success story Boys & Girls Clubs were created to support. One of six kids, Arroyo was born in Mexico and moved to the United States at age 3 on July 4, 1969. “I figured the fireworks were for us,” she recalled. Arroyo’s father had lived in Santa Barbara before, having helped build the Earl Warren Showgrounds in the 1950s as part of the Bracero guest-worker program.

The family moved to the Westside when Arroyo was 7, living in public housing on Coronel Place. She attended McKinley Elementary — which she loved — and remembers having a UCSB mentor who took her to the campus. “I remember I wanted to be an attorney,” she said. She attended Santa Barbara Junior High School, Santa Barbara High School, and was poised for college. But at age 17, Arroyo landed a job with First Interstate Bank through a work-training program. She moved up the ladder quickly, and by age 19, Arroyo — always entrepreneurial — was promoted to assistant manager.

For the next 24 years, she enjoyed a successful banking career. She also immersed herself into the world of Santa Barbara’s nonprofit community. She was awarded the prestigious Katherine Harvey Fellowship, which goes to promising young philanthropists; she counted Anne Towbes, wife of developer-banker-philanthropist Mike Towbes, as her mentor. By the time the banking industry imploded a few years ago, Arroyo was already itching to jump exclusively into nonprofit work. More specifically, she wanted to run the Westside Boys & Girls Club. It was an important part of her childhood. She had attended programs there since she was 5, even though it was then known only as the Westside Boys Club. “I had my eye on it,” she explained. “It’s where I grew up,” she said.

United We Stand

Five years ago, four Boys & Girls Clubs (Carpinteria, Westside, Goleta, and Lompoc) merged together, along with Camp Whittier (located near Lake Cachuma), to form the United Boys & Girls Clubs of Santa Barbara. The hope was that together, they could achieve a financial stability that had eluded each of them separately. The thinking was that the new United administrators could focus on fundraising and paper work, leaving club directors to focus on programs and kids. About three years ago, it became apparent that wasn’t enough, according to Rattray. In 2009, he said, United was losing about $5,000 a day. There was little management or oversight when it came to coordinating revenues and expenditures and even less when it came to integrating club programs into broader community needs. Rattray, a former defense-industry executive who spent 35 years with Raytheon before taking what he termed an early retirement, said, “Some foundations had pretty much given up on us. We had to reinvent ourselves.”

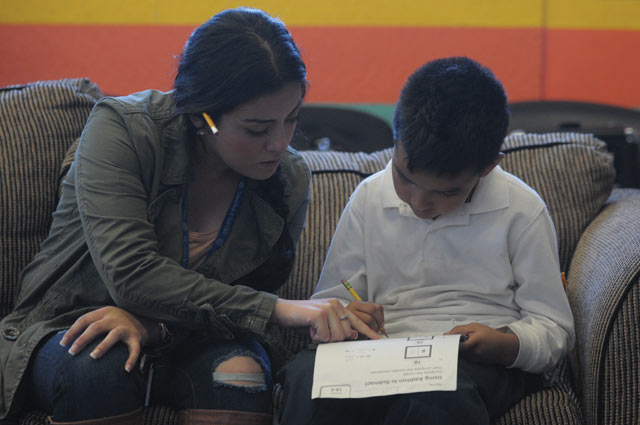

Part of that reinvention led, in fact, to Rattray’s hiring as CEO. Under the new scheme, clubs are no longer places where kids simply drop in after school, shoot pool and hoops, hang out, and mess around. According to Rattray, they are now “Learning Care Centers,” or “conveyor belts,” where kids from kindergarten to age 18 are equipped with age-appropriate life skills — via a strategy of “fun learning” and “high-yield activities.” Rattray believes the clubs’ programs can help drive home certain classroom lessons. For example, kids shooting pool could be reminded about the geometry of angles, or kids playing in the creek might get some hands-on biology. Under Rattray — an accountant and an engineer by training — United managed to do substantially more with less, cutting costs by about 7 percent and increasing the number of kids using the clubs from 3,500 a year to 5,000.

And nowhere has that increase been as dramatic as at the Westside club. Since Arroyo took over two years ago, the numbers have jumped from about 40 kids a day — mostly older teens — to 200. Paid memberships — which cost $20 a year for services that club administrators estimate cost $700 per child to provide — ballooned from 70 to 1,300.

But it didn’t happen overnight.

The Long Way Home

On Arroyo’s first day, she found the building in such a mess she needed a butter knife to pry open most of the doors. Parents felt intimidated by the older teens — some gang members — hanging out around the club’s pool tables. Arroyo couldn’t blame them. She felt intimidated herself.

First she got the building painted and found new furniture. Then she told everyone over 18 they’d be welcome only if they worked as volunteers. But to do so, they’d have to pass the volunteers’ screening requirements, something anyone on probation could not do. And according to Officer Jim Ella, head of the Santa Barbara Police Department’s gang unit, Arroyo was “very proactive” in calling the cops at the first hint of trouble. But she also invited those with possible gang affiliations — “I don’t like the term ‘gang member.’ I refer to them as young people.” — to use the club’s basketball courts in the morning hours before the club opened for business. Also by inviting taggers to do paint murals on club grounds, she reduced the amount of graffiti. “I know when I have my hands full,” she said, “they’re often the first ones to offer to help.” And when they ask for jobs, as they often do, Arroyo sees that they get help writing résumés and are schooled in how to conduct themselves in job interviews.

But the shadow cast by Bohnett Park — and its long association with Westside gang activity — cannot be overstated. According to city police who’ve worked that area, the problem is both real and exaggerated. Demonstrating how scary the neighborhood could be, CEO Rattray pointed to four bullet holes sprayed into one club window 10 years ago. That’s why, he explained, anyone on probation for gang activity won’t be allowed in. But as Arroyo looked out another window — this one overlooking a Bohnett Park filled with very young kids — she noted the conspicuous absence of anyone looking like a gang member. For her, the reason seemed simple: Gang members don’t like hanging out with young kids. “They bug,” she said. “Young kids just bug.”

Under Arroyo, younger children have been coming to the Westside club in great numbers. Every day, 90 children attending schools from all over town arrive at the club in three vanloads. Among other things, the club offers preliteracy training so preschoolers have a head start on fundamental reading skills. Most importantly, by creating greater separation between the ages, Arroyo has provided an environment to which protective parents feel far more comfortable sending their younger kids.

Hitting the Right Note

Endowed with an annual budget of $242,000, the Westside club is hardly brimming over with cash. That pays Arroyo’s salary, as well as seven other employees, including Bernard Hicks, who has coached basketball there for the past 13 years. He also takes kids on outings to the beach, or for tacos, or to the Boys & Girls Club camp near Lake Cachuma. “A lot of times, that will be the only opportunity they’ve had to leave the neighborhood,” Hicks said.

Arroyo has proved ingenious in leveraging limited funds to partner with other organizations in a better position to provide actual services. “We can’t do everything,” she said. “It’s crazy to try.” To this end, she’s opened up the Westside to the Santa Barbara Elite team of cheer dancers. This year, 80 dancers from the Westside club took their act to competitions in Las Vegas and Knott’s Berry Farm.

Two years ago, Notes for Notes opened up music studio space in the Westside club, providing much needed resources to students. Turntables and computers are available for prospective deejays; instruments are available for anyone hankering to learn to play. Notes for Notes provides the instructors, insurance, and “the vibe”. There is no censorship, no program to which they must adhere. Teens are encouraged to express what they feel, however raw. “If you make it part of some broader program, like anti-drugs or anti-gangs, kids are going to think it’s just a trick to make them not do something else,” said Philip Gilley, cofounder of Notes for Notes. “And it won’t work.” He estimated 10 to 20 kids a day use the space. Last year, 10 young musicians from the program opened for Steve Miller and Seymour Duncan during a benefit concert at the Lobero Theatre.

The club offers classes for teens on having healthy relationships and on how to manage their money. And one of the most popular programs is Teen Talk, during which kids discuss subjects that have been anonymously dropped into a suggestion box. So far there has been no shortage of heavy topics — abuse, divorce, addiction, and suicide.

There’s No Place Like Home

The Westside club has become home away from home for many kids whose parents work two jobs, who share their apartment with two other families, and for whom there are exceedingly few recreational opportunities. A group of three 13-year-old girls told this reporter that when they get into “melodrama” with one another, they seek advice from Arroyo. Likewise, when parents find themselves exasperated by their mouthy, defiant teens, they turn to Arroyo.

“We have kids bouncing off the walls here,” acknowledged Arroyo. “I mean really bouncing.” To help kids inclined to use their fists rather than their words, Arroyo obtained a grant to hire special mentors assigned to provide one-on-one attention. During one of our recent interviews, a 3rd-grade boy, accused of shoving another child, interrupted Arroyo to plead his case. He’d been provoked; the other boy had called his mother “a son of the B-word.” And he only pushed him a little bit. Arroyo wouldn’t let him off, so he had to take a time out by himself. But like a lot of the kids there, he called her “Mom.”

Chana Ortiz, a single mother with two children who moved to the Westside a few months ago, was initially apprehensive about the neighborhood. She worried her 8-year-old son, a special-needs student, might be bullied by other boys. And in fact, he was — at the Westside club. Ortiz was impressed by how seriously and swiftly Arroyo took charge of the situation. But even more, she was impressed that Arroyo talked directly to her son — not to her — assuring him that bullying would not be tolerated. It worked. Her son now loves the computer stations at the Westside club, and her daughter has thrown herself into dance classes. “They’ve really thrived,” Ortiz said. Both her kids got bicycles this past year, donated through the Westside club. Both children have spent time at Camp Whittier. “When I come to pick them up, they’ll get upset. It’s like, ‘Why are you here?’”

At a time when the Westside club may be forced to bite the bullet, Arroyo is absorbed by what still must be done. The club needs to stay open on weekends. Isn’t that when young people need to be off the street? She points with pride to the teen dance organized by her Keystone leadership group in February. More than 300 people showed up — from all over town — and danced until midnight. “There was not one incident,” she said, “and they raised $1,000.” A New Year’s Eve dance drew a crowd of 408, and again, she stressed, there was no trouble. Training the young deejays for the most recent dance was Miguel Benitez, a 17-year-old attending La Cuesta. Benitez, who deejays himself most weekends, got involved with the club about nine months ago. Younger girls like Vanessa Gonzalez, Tatiana Jimenez, and Arroyo’s own daughter, Breanna Case, said they appreciate how they can talk to Benitez about anything. He said his experience at the club has inspired him to become a junior high school teacher. When they heard the club was in financial trouble, the four of them walked along State Street asking various businesses for financial help. “It’s important,” said Benitez. “It’s a place where you can be safe and be yourself.”

As for Arroyo, she is confident the club will survive. Too many lives depend on it, she said, and she knows many wealthy people from her days as a banker. Furthermore, she has a job she loves, and she intends to keep it. “How many people go to work every day and are told how great they are? How many people get hearts almost every day?” she asked. “Well, I get that. Who wouldn’t want my job?”