Tipping-Point Art

Jane Gottlieb and Philip Koplin

Two new shows on exhibit this month in Santa Barbara contain work that solicits a mental transition from one way of looking to another. In her exhibition Vivid, at Wall Space Gallery (113 W. Ortega St.) until April 1, Jane Gottlieb shows 20 of her altered photographs, which, with their bold composition and intense, supersaturated palette, feel like stumbling into the acid dreams of some well-heeled extraterrestrial. Over at The Project Fine Art Zone (740 State St., Ste. 1), Philip Koplin has set up an exhibition called flying falling in a funky closet space. Koplin’s singularly faux-naïve idiom mixes George Herriman imagery and abstract painting surfaces with a whole lot of happy randomness. What Koplin and Gottlieb have in common is a way of quietly nudging the viewer over into a new mindset. Call it tipping-point art, because it’s focused on the place where one angle of vision pivots to become another.

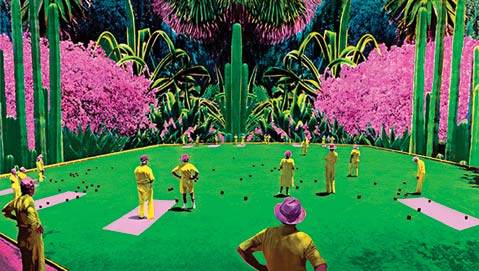

Take Gottlieb’s amazing triptych “Lawn Bowlers,” subtitled “Death,” “Life,” and “Resurrection.” Gallery director Crista Dix has them hung perfectly, offering ample space and time to let these sneaky mindbenders do their thing. On the right “Lawn Bowlers – Resurrection” shows a party of lawn bowlers arrayed on a luridly green and pink pitch in front of an ambiguous light source that’s rending the sky. It’s even more disconcerting in its way than “Lawn Bowlers – Death,” which portrays the same scene unfolding under an ominous desert sky lined by little fluffy clouds. It wasn’t until I had gazed for some time at the central image, “Lawn Bowlers – Life,” with its backdrop of Miami Beach–style advanced topiary, that I realized what was causing my eerie sense of déjà vu. While the backdrops in these three images shift radically, the foreground image in each, right down to the position of the balls on the field and the stances of the bowlers, remains exactly the same. When seen together as a triptych, the pictures establish a weird interference pattern among themselves, with the shifting backgrounds serving to distract from the static foreground image. Put in those terms, the experience sounds dry, but in person it is anything but. The “aha” moment here really sings, and leaves behind an after-elation at having “solved” the image, even if that solution is in itself meaningless. That’s life, and it’s a lot like lawn bowling.

Walking into Koplin’s falling flying, one can’t help but be charmed by the amiable menagerie the artist has conjured. There are the affable figures of “Two Spliced Mice,” the delicate single-line flowers of “Night Garden,” and the shambling bear of “Sunday Morning Stroll in Mooseville,” and all of them coexist happily without a lot of fuss. Koplin writes in an artist’s statement that he thinks of his work as a way of “masquerading his shortcomings as aesthetic choices,” but the more one looks at them, the more these images push and pull the mind and eye in all kinds of unexpected directions. Starting with drawing as his base, Koplin builds palimpsests of image, marking, erasure, and surface that effectively resist rapid resolution and categorization. Are these naïve drawings, abstract works of art, deliberately incomplete gestures, or all of the above? As with Gottlieb’s images, the viewer is drawn into an active response, and the result is aesthetic pleasure — wearing mouse ears.