Eccentric Multimillionaires Living in Poverty

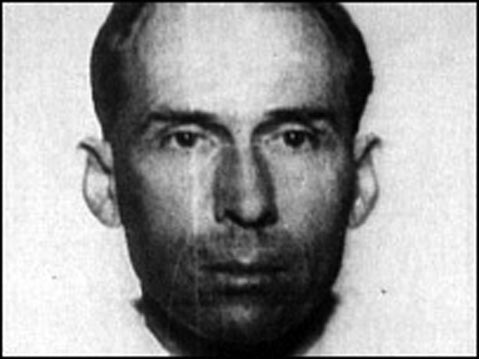

John Figg-Hoblyn and His Sister and Faithful Companion Margaret Were Often Seen Walking the Downtown Streets

A DICKENSIAN TALE: It’s a Santa Barbara story out of a Charles Dickens novel: an eccentric brother and sister living a life of poverty for decades while turning their backs on an English estate worth millions.

You have a snarled “entailed” property, as in the Downton Abbey Masterpiece Theatre series, along with echoes of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility.

And, as Santa Barbara attorney Philip Marking noted in a document I found among stacks of the Figg-Hoblyn case files at the Santa Barbara Courthouse, the years of legal knot-untying bring to mind Dickens’s 1853 novel, Bleak House.

“In Bleak House, the Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce will contest was finally settled after decades of muddled litigation, only for the claimants, many of whom had gone mad from years of frustration, to find the Jarndyce estate had been consumed by the cost of the proceeding,” Marking wrote. There was no money left.

“Fortunately,” Marking said, this case “had a much better ending.” It’s been one of the most novel, complicated, long-running cases in Santa Barbara Superior Court conservatorship history, piling up thousands of pages of documents — and thousands of dollars of legal fees on both sides of the Atlantic.

I remember seeing John Paget Figg-Hoblyn, walking the downtown streets years ago with his sister and faithful companion Margaret. They lugged backpacks and ignored my questions about the 960-acre Cornwall estate that waited for John to make his claim to it.

He never did, for reasons that remain a mystery. Searching for the pair, I once visited the rundown Carpinteria trailer park where they lived in a dilapidated vehicle. (They weren’t home.)

Before John died last June at 85, his Cornwall property was locked in the centuries-old “entail” system, whereby the eldest male heir inherited everything. It was one of the last of England’s entailed estates.

That meant that upon his death, it would have gone to a California cousin, John Westropp Figg-Hoblyn, leaving his sisters, Margaret and Anne Auld, out in the cold.

And that is where Margaret, now 78, has been living off and on in recent years. Attorneys and courts here and in England made legal history by managing to end the entail by creating a will before John Paget’s death. As a result, the estate, now estimated at $4,760,310 and under court administration in England, will go to Margaret and Anne. John Westropp, who unsuccessfully contested the action, gets $200,000.

Margaret (like John Paget, a Stanford University graduate) “has a long history of homelessness and tent-living,” and a few months ago, she “was discovered in a starved and disheveled state,” according to a county conservator’s report.

She was being evicted from her latest place, and the next stop was out on the street, conservators said. So they stepped in. Now, she’s a multimillionaire, on paper at least.

Although part of the property, considered prime farm land, has been sold to benefit the estate, much of it is still tied up, awaiting sales, according to a conservator report.

John Paget’s grandmother, Rosalind, daughter of Squire William Paget Hoblyn, one of the landed gentry of Cornwall, emigrated from England to Santa Barbara in the early 1900s with her husband, Thomas. (That was after she disgraced the family by running off with a married coachman.) The family’s land at the Rincon was eventually taken by the state for freeway work.

The three Figg-Hoblyn heirs, despite their potential wealth, have coupled eccentricity with reduced mental capacity in their old age. Conservators had to be appointed for them. Could it be the curse of the Figg-Hoblyns, as one documentary put it? After being located earlier this year, Margaret was diagnosed as afflicted with dementia, with a long history of paranoia and delusion, and now lives under care in Ojai. She has no children, but Anne, in Marin County, has two daughters who stand to inherit the Figg-Hoblyn wealth upon their mother’s death.

That is unless, of course, new Dickensian legal tangles emerge. Speaking of that famous author, the team that helped untangle the complicated entail snarl included Farrer & Co., a London firm dating to the early 17th century and whose clients included Dickens himself.

Further complicating matters, “There have reportedly been attempts to take advantage of her financially,” a court-appointed psychologist for Margaret reported. A conservator’s attorney for John also criticized an unnamed group of “do-gooders” with “suspect motives.”