Danger on the Rails

The Inside Track on Train Safety

It is 2:40 p.m. on a quiet Monday at the beach near Santa Claus Lane. There are perhaps 40 people walking on the sand, a handful of dogs playing at the water’s edge. A woman crosses the railroad tracks with her baby strapped in front of her. Just another day in paradise.

At 2:45:13, a woman walking her dog heads across the tracks on the way back to her car. Just as she crosses, the railroad light at Padaro Lane turns green, signaling that the northbound Pacific Surfliner is heading her way. A hundred yards east of her, another woman also crosses. She’s not paying much attention as she looks for an opening in the fence that Union Pacific Railroad put in a few years ago, ostensibly to keep sand off the tracks.

At 2:45:30 she looks up, startled, as the Surfliner turns the corner. There’s a moment of hesitation — like she’s thinking which way to go — then she bolts to the right through the fence to safety. At 2:45:42 the train hurtles by, just 12 seconds after it first appeared in sight. Another second or two of hesitation, and she might have been in trouble.

In 2007, Alan Shapiro, owner of the nearby Black Eyed Susan’s shop, was not so lucky; he was killed by a similar northbound train. Witnesses say they saw Shapiro walking his dog, which was not on a leash, while talking on his cell phone. When the dog wandered onto the tracks near the Sand Point Road crossing, he chased after it, trying in vain to save it from the oncoming train.

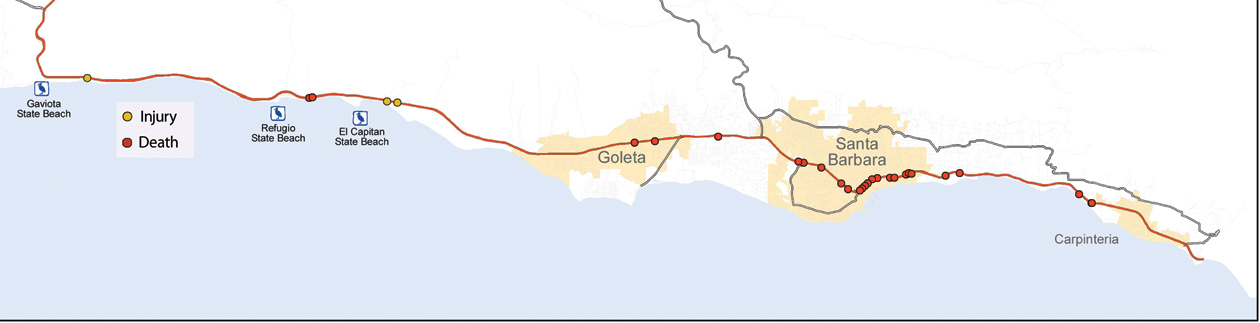

Statistics from the Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Analysis note that from 2000 through 2011 there were 38 fatal pedestrian-train incidents in Santa Barbara County.

On January 2, 58-year-old Pamela Price was killed near the railroad crossing along Butterfly Lane. Six months earlier, another woman was killed a half mile east at the Eucalyptus Lane crossing. While some of the deaths (including the one February 4 near the Amtrak Station) appear to be suicides, pedestrian-train accidents have become the leading cause of death on the rails: Approximately 500 people are killed every year across the country, with California leading the way.

No Trespassing

So far, efforts in the Santa Barbara area to reduce train deaths have revolved around law enforcement tactics. Crackdowns through the federally funded Operation Lifesaver program, which cites people for trespassing, have mostly taken place within the City of Santa Barbara stretch of the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) tracks. Fines are typically $475, but the citations are rarely given.

The problem, according to Matt Roberts, Carpinteria’s director of Parks and Recreation, is that Union Pacific effectively blocks safe access to the coastline. “We have three miles of some of the greatest beaches and coastal resources, and there’s only one way for the public to access that,” he said. “That’s not right.”

In Carpinteria, the only sanctioned public route to the beach is along Linden Avenue, which has an “at-grade” crossing near the Amtrak Station. “The only other crossing we can use goes directly into the State Beach parking area,” Roberts added. “What we have here in Carpinteria is an urban population separated from the coast by a 100-foot-wide ‘no trespassing’ zone that stretches from one end of town to the other.”

What is true of Carpinteria is also true in other parts of the county. Union Pacific property averages about 100 feet wide over the 45 miles of track that run from Gaviota State Park to Rincon. Along the Gaviota Coast, the only public routes to the ocean are at Gaviota, Refugio, and El Capitán state beaches. Other places are accessed by traversing private or railroad property — among them Corral, Vista del Mar, and San Onofre beaches — locations that offer plenty of space to park but aren’t designated for legal access. Surfers face similar problems trying to get to Naples Break or Edwards Point.

Building Safe Access

I was peering over Roberts’s shoulder in his office at Carpinteria City Hall as he fired up Google Earth, and we began to look at a number of locations most vulnerable for the next potential accident. He quickly zoomed into a spot near Aliso School. “A lot of the kids come from these apartment complexes near the salt marsh,” Roberts noted. “But every morning, they head over to the tracks, follow them west across the railroad bridge, and onto the school grounds.

“Here’s another spot,” Roberts went on. “Calle Ocho, which is a half mile east of Linden. It leads directly down to Tar Pits Park, but there’s no way to get there without crossing the railroad tracks.” In 2009, a Carpinteria resident almost died near Calle Ocho when he fell while crossing the tracks. The train barely stopped in time to keep from running him over.

Perhaps the most dangerous location of all is the Carpinteria Bluffs, a 52-acre open space that leads to the beach and out to the Harbor Seal Rookery overlook. “We haven’t done any specific studies,” Roberts explained, “but we know that there are at least 100,000, and more likely close to 200,000 people, who cross the tracks each year — all of them illegally.”

In 2009, thanks to Roberts’s efforts, Carpinteria was awarded an $80,000 grant for a Coastal Access Feasibility Study. The exhaustive 90-page report noted a “long-term pattern and practice of unsanctioned crossing of the UPRR corridor at numerous points within the city.” It identified 12 areas of concern that included the three spots identified by Roberts.

“There are basically three ways to get across the railroad tracks,” Roberts explained. “Over-crossings, underpasses, or at-grade crossings. Union Pacific has told us they’ll oppose using at-grade crossings for pedestrian or bicycle use, and over-crossings have serious visual impacts, so we’re looking at underpasses as the way to go.” The study estimated they would cost between $1.7 million and $2.2 million each, depending on the location.

Carpinteria is quietly buying up property along the tracks at Holly Avenue as part of a partnership with Union Pacific to construct underpasses there and at Calle Ocho. “We own the land on both sides of the tracks at Calle Ocho, and the City Council will be meeting soon to discuss purchase of a section of Union Pacific land on the south side of the tracks at Holly Avenue,” Roberts said. “When that happens, we can start talking about underpasses in both places.”

Getting the right-of-way to add an underpass at the Carp Bluffs isn’t quite as easy. The spot where the trail crosses the Union Pacific tracks is owned by a Las Vegas limited partnership called Carpinteria Partners. Currently, the partnership land north of the tracks is leased for agricultural uses. “Their land on the south side of the tracks won’t ever be able to be developed,” said Roberts, “and it’s used every day by those heading to the beach or the seal overlook, but we won’t be able to move ahead until we are able to secure an easement there.”

Santa Claus Lane Upgrades

Just a mile away, on the west side of Carpinteria Salt Marsh, the county is moving to solve the decades-old problem of safe beach access at Santa Claus Lane. Trespassing across the tracks there is as dangerous as any place on the South Coast, and some consider it to be the number-one spot for the next major accident. On a typical weekend, there are 200-300 people on the beach, quite a few of them families. It’s an almost perfect spot — easy entry, wide expanses of sand, and plenty of space for kids to play. But there are about four minutes a day when the trains pass by and the tracks become a high-danger zone.

“The trains only come by here a few times a day, but when they do, you’ve got about 12-15 seconds to decide what to do when one of them comes round the corner,” said Rosie Dyste, lead planner in the county’s Long Range Planning Division and its efforts to create a safe at-grade crossing at Santa Claus Lane. The problems there have been long recognized. “The Toro Canyon Plan was the first to prioritize Santa Claus Lane parking, beach access, and streetscape issues in the late 1990s,” Dyste explained, “but there were a lot of issues that needed to be addressed that would end up taking quite a bit of time.”

“This has been a true collaborative project,” said 1st District Supervisor Salud Carbajal. “Local businesses, Caltrans, the local community, and funding sources such as the California Coastal Conservancy have all been a part of making this happen.” As we discussed the project, Carbajal listed the reasons why he has made the Santa Claus Lane project one of his top priorities. “The safety issue, providing safe access to the beach for individuals and families, is absolutely critical,” he said. “The project will also provide a range of amenities such as parking, bathrooms, trash collection, and showers, and it’s a real benefit to the entire community.”

Until the county purchased two vacant beach parcels in 2008 on what most people erroneously assumed was a public beach at Santa Claus Lane, most of the land south of the tracks was privately owned. “There were also issues relating to coordinating with Caltrans, working with the business owners, Union Pacific Railroad, and the ever-present need to find funding to continue with the project,” Dyste added.

Things began to heat up in 2010 when the Long Range Planning Division received Coastal Resource Enhancement Fund grants to move ahead with the project, and Santa Claus Lane business owners sponsored a community meeting to gather public input. On January 17, 2012, the county held a second neighborhood meeting to present concept plans for review and comment. In August 2012, Long Range Planning released its Santa Claus Lane Circulation and Parking project report that evaluates improvements and includes a location for an at-grade pedestrian crossing. Next up are the preparation of conceptual design plans for the crossing and the submission of a formal application to the California Public Utilities Commission (PUC) this spring. “We’re in a ‘full speed ahead’ mode right now,” Dyste said. She hopes the project will receive permits and be shovel-ready by the middle of 2014.

“I’m committed to moving heaven and earth to make this happen,” says Carbajal. “It’s a no-brainer! It’s good for everyone! I’m optimistic, confident, and hopeful that the PUC will work with us to make this happen.” Noting that the Union Pacific Railroad has been hesitant in the past to approve new at-grade crossings, the supervisor affirmed he’d be willing to engage the State Legislature if that’s what it takes.

Risky Rural Routes

While the swath of land from Gaviota State Park to El Capitán State Beach has some of the most beautiful, secluded, and inviting beaches anywhere in Santa Barbara County, solving the coastal access issue in such rural areas presents additional challenges. “I love this part of the coast,” said a man heading down to the beach from the San Onofre Canyon dirt parking area. “It’s so quiet, and when the tide is lower, you can walk for miles without seeing hardly anyone.”

“There are eight informal access points from Gaviota to El Capitán that require the public to trespass across the tracks,” Rich Rozzelle, Channel Coast District superintendent for California State Parks, said at a recent Gaviota Coast Planning Advisory Committee (GavPAC) meeting. “Just because the public is using them doesn’t make it legal.” Rozzelle estimated that 25,000 to 50,000 people utilize these routes.

Although GavPAC has included several of these locations in its recommendations for upgrading beach admittance, Rozzelle doesn’t believe the proposals are realistic. “The amenities needed for establishing new beach access is extremely costly,” he explained. “They require on and off ramps, bathroom facilities, trash collection, and the like. And that doesn’t take into account getting across the railroad tracks.” At-grade crossings like the ones being proposed in Carpinteria or at Santa Claus Lane aren’t practical either, Rozzelle added.

“Crossing the tracks anywhere on the Gaviota is extremely dangerous,” he said. “The trains run much faster than in the urban areas, and because there aren’t very many legal at-grade crossings, they aren’t required to sound their horns as often.”

Eric Hjelstrom — newly appointed Santa Barbara Sector superintendent for Gaviota, Refugio, and El Capitán state beaches — echoes that concern. Hjelstrom served as the three parks’ lead ranger for many years before his appointment as superintendent. “In the past five years, we’ve had three fatalities and several more pedestrian-train accidents that have resulted in the loss of limbs. When they happen, the accidents are absolutely horrible.”

Corral Beach, known as “Hazards” by local surfers and one of the more popular trespass points, is an example of what can happen at these informal crossing areas. “I personally have been the first person on scene there twice for pedestrian-train fatalities,” Hjelstrom told me. “In one case, a surfer sat down on the tracks to watch the sunset and have a beer, and never heard the train coming. In another a husband and wife stopped at the Corral parking area to look for a camping spot. With his wife watching, the husband was killed when he attempted to cross the tracks.”

The trains are wider than they look. Many of the injuries occur when people think they’re far enough away but really aren’t. In 2009 near the Vista del Mar beach access point, a group of friends were heading down to the beach when they noticed one of the party was missing. Upon tracing their steps back up to the bluffs, they discovered her lying by the side of the tracks. Though she didn’t die, she did lose an arm. Another person lost a limb when he stopped to urinate near the entry to Brad Pitt’s beach getaway and was too close to the tracks.

Emotional Trauma

If accidents such as these are horrendous for first responders and train passengers who witness them, the impact is beyond horrific for the engineers who pilot the trains. “At the first sign that a person or vehicle may be in danger of being hit, the engineer blasts the horn,” Amtrak spokesperson Vernae Graham explained. “But it may take 250-300 yards for one of the lighter trains like the Surfliner to come to a stop.” On the winding Gaviota Coast, there is often no way for the train to come to a halt before it reaches most of the informal access points.

“Once they’ve hit the emergency brakes, the engineer has the opportunity to step behind a door or go into a small room in the cab before the collision occurs,” Graham said, “and this helps them avoid the actual impact, but it can still be extremely traumatic for the engineer.” Graham noted that Amtrak counselors are called immediately to offer both the engineer and conductor support. “The engineer doesn’t get off the train,” Graham added. “It’s the job of the conductor to get off and assess the situation. That can be as hard on that person as it is on the engineer, if not worse.” Amtrak also offers an Employee Assistance Program for those who’ve gone through such an incident whereby any crew member can ask for relief with no questions asked.

Incidentally, though many of the pedestrian-train accidents in Santa Barbara County involve Amtrak trains, responsibility for the tracks belongs to their owner, Union Pacific Railroad, and, as such, Union Pacific is charged with minimizing trespass. The task of preventing it in rural locations such as the Gaviota Coast is almost impossible. Union Pacific representatives declined to comment for this story.

Though GavPAC has recommended improvements at several of the informal access points, there is a hesitancy to push too hard for fear that Caltrans might close them off, either by posting “No Parking” signs or adding barriers. At GavPAC meetings, several in attendance have noted the increase in the number of “no parking” zones near the state beaches and wonder if other access will be closed as well if people complain too much.

Stop, Look, and Listen

As noted in the 2009 Carpinteria study, people will cross the railroad tracks if they can’t get to the beach any other way, despite the danger and the threat of being cited for trespassing. Though it’s been possible to make periodic sweeps through high-use areas such as downtown Santa Barbara, it’s difficult for Union Pacific to enforce its rules on the more isolated parts of the coast.

In the end, it comes down to the vigilance of those who make the decision to cross. Perhaps the most important thing to take away from the study is what might be termed the “large object phenomenon,” which states that people tend to misjudge the speed at which a very large object, like an Amtrak train, is traveling. In fact, people often think big objects are moving slower than they actually are.

The study also notes this phenomenon is further compounded by “object familiarity.” People will look at a speeding train but judge its speed based on their familiarity with a car. This error gives them the false idea that they have more time to take evasive action than they really have. Ultimately, what may be required to reduce deaths on the train tracks is something relatively simple — for people crossing the tracks to pay attention to their surroundings and to be aware of the dangers posed by a train in motion.

Blowing One’s Horn

If you live anywhere along the rail corridor in Santa Barbara, you know when the train is coming. You may never see them, but you sure can hear their horns. The ear-splitting blasts weren’t always a part of life on the tracks. Prior to 1994, horn rules were left up to the state and local communities. In the early 1980s, Florida banned them.

Within the next few years, Florida’s accident rate doubled, and in 1991, the Federal Railroad Administration issued Emergency Order 15 requiring the Florida East Coast Railroad to sound locomotive horns at all public highway–rail grade crossings. The order preempted state and local laws that permitted nighttime moratoriums. This was followed by the passage of an interim Horn Rule in 1994. After extensive studies, the rule became final across the country in 2005.

As a result, trains or engines approaching public highway grade crossings are required to sound their horns for at least 15 seconds, but no more than 20 seconds, before the lead engine enters the crossing. Trains traveling at speeds greater than 45 mph must begin sounding their horns at or about, but not more than, one-quarter mile (1,320 feet) before the nearest public crossing. The signal is required to be prolonged or repeated until the engine or train occupies the crossing or, where multiple crossings are involved, until the last crossing is occupied.

The blast of the horns goes something like this: —— – —, where the “—” represents a longer blast and the “-” a shorter one.

The horn rule also requires that the interests of communities be taken into account and that they be allowed to establish “quiet zones” — sections of a rail line at least one-half mile in length that contains one or more consecutive public highway–rail grade crossings at which locomotive horns are not routinely sounded — if the risk is at, or below, two times the Nationwide Significant Risk Threshold and if there haven’t been any relevant collisions within the quiet zone during the preceding five years.

For an extremely detailed look at the effort by the County of Santa Barbara Public Works Department to establish a quiet zone that would start at the Santa Barbara City limits and go east to the city limits of Carpinteria, a distance of 6.25 miles, go to countyofsb.org.