Empty Mansion Fills With Promise

Clark Estate Settles Mansion, Oceanfront Property on Santa Barbara

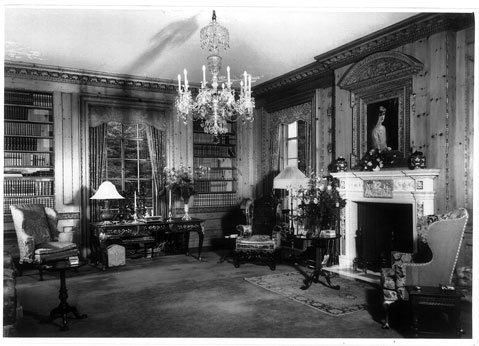

Santa Barbara has a new public treasure — Huguette Clark’s former estate Bellosguardo. Now the magnificent 23.5-acre property that’s been sitting empty at 1407 East Cabrillo Boulevard for almost 60 years belongs to a specially created entity known as the Bellosguardo Foundation. With 1,000 feet of ocean frontage and only the quiet folks in the Santa Barbara Cemetery for neighbors, the spectacular mansion on the bluff above East Beach has to be the most conspicuously unoccupied private home in Southern California. Vacant except for a team of caretakers and groundskeepers since the 1950s, Bellosguardo has for many years been kept in Huguette Clark’s preferred state, which is as close as possible to the way it was when her mother, Anna Clark, lived there in the 1930s. The result is already a kind of museum, as rich in period plumbing as it is in period furniture.

What’s more, through the auspices of the Bellosguardo Foundation, this one-of-a-kind property will also belong to the city of Santa Barbara. According to the settlement, which was administered by the Attorney General of New York, seven of the 10 initial members of the Bellosguardo board will be nominated by Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider. In a statement expressing her satisfaction with the agreement, Mayor Schneider identified the foundation’s primary mission as “to open the Bellosguardo house and gardens to the public as a center that will foster and promote the arts.” In her remarks at the annual Santa Barbara Beautiful awards ceremony, held on Sunday, September 29, at the nearby campus of the Music Academy of the West, Schneider called on the community to “dream big, and dream bold” about what to do with what has up until now been a conspicuously underused asset. Many questions remain, however, not only about the condition of Bellosguardo, but also about the city’s benefactor, Huguette Clark. Why was the property empty for so long? Who exactly was the reclusive Ms. Clark?

As with so many features of Clark’s long and mysterious life, the gift of Bellosguardo to Santa Barbara presents an enigma. While she was alive, the buildings and grounds were almost entirely dormant, as were several other extremely valuable properties that she owned, including an estate in New Canaan, Connecticut, called Le Beau Château and two enormous apartments in a luxury building on 5th Avenue and 72nd Street in Manhattan. Huguette Clark inherited a fortune of approximately $300 million from her father, the copper king W.A. Clark, and she could have lived anywhere in the world, but instead she chose to spend the last decades of her life in a darkened hospital room, administering her affairs by phone, letter, and most often, personal check.

While the establishment of a center for the arts at Bellosguardo appears likely to entail some additional fundraising, it’s absolutely certain to require considerable creative thinking, as well. The task of taking the measure of Huguette Clark will render the formulation of an appropriate identity for the Bellosguardo Foundation an interesting challenge. What kind of public institution will best reflect the spirit of a woman who for most of her long life declined to go out in public?

From Recluse to Best Seller

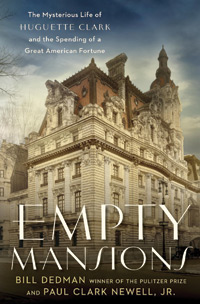

The question of what Clark intended that her Santa Barbara property would become is only one of the many riddles addressed by a fascinating new book. Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr. has gotten not just Santa Barbara but all of America reading and talking about Huguette Clark. Through the popularity of this highly readable account of her life, an elderly woman has gone from her status of three years ago as an ultra-recluse, when she was nearly un-findable and living under an assumed name in a nondescript New York hospital room, to the top of the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. And if the story of Clark’s very private life can stir so much interest, who knows what will happen in Santa Barbara when those East Cabrillo gates finally open?

Since its publication on September 10, Dedman and Newell’s brilliantly researched, tough-minded, and fair volume has spent two consecutive weeks in the top 10 of the New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. Despite engaging a host of employees while she was alive — including doctors, lawyers, accountants, caretakers, and nurses — Clark remained an elusive figure, rarely showing more than one side of herself to any single person. Her relative Paul Clark Newell Jr. spoke to her some 50 times on the phone, and his recordings of these conversations are a bonus available with the audiobook edition of Empty Mansions. But without the skills of Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative journalist Bill Dedman, who humbly refers to himself as being a “public records reporter,” it’s unlikely that the story would ever have come together so fully or shot to best-seller status within a week of publication. An investigative specialist beautifully matched to the unusual nature of this subject, Dedman makes the stories of Huguette Clark and of her father, William Andrews Clark, a fascinating read that’s even harder to pin down than it is to put down.

Before getting too far into the story of Empty Mansions, it might be useful to review what we know about the current status of the estate. The full settlement document runs to 81 pages, but for Santa Barbara, the suspense is on page two, which includes the following clause:

That there will be formed pursuant to the Will a charitable organization (the “Foundation”) to which the decedent’s property located in Santa Barbara, California at 1407 East Cabrillo Boulevard, known as “Bellosguardo” (the “California Real Property”), and various other items of personal property and cash are to be distributed.

Credit for negotiating this extraordinary (and hotly contested) bequest and for the leading role given to the mayor of Santa Barbara in charting the foundation’s initial direction, should go to the legal team of Price, Postel & Parma partner Jim Hurley, former mayor Sheila Lodge, and philanthropist Bob Emmons. The trio formed a Bellosguardo Foundation here in California in advance of the proceedings, and even when that initial attempt to negotiate on the city’s behalf was determined by the New York court to be without standing in the case, they nevertheless managed to find a way back to the negotiating table in time to win not one but two favorable decisions — the bequest itself and control of the board.

The heavily lawyered proceedings, which took place in the office of New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, did not leave all who were expecting something from the estate equally happy. The members of her extended family — all relations from her father’s first marriage — will split approximately $34.5 million, but Clark’s former nurse Hadassah Peri, who received millions in personal gifts while Clark was still alive, gets nothing and will have to pay back approximately one-fifth of what she was given. (New York state law treats personal gifts — especially cash — that go to so-called confidential employees such as private nurses to be tainted by default.) Clark’s extensive doll collection, which is valued at nearly $2 million and was set to go to Peri, has been reassigned to the care of the foundation. Welcome to your new dollhouse.

Some of the details of the complex financial state of affairs left behind by Clark are still not resolved. Until the Internal Revenue Service weighs in on some substantial fees due on delinquent gift taxes, it will be hard to gauge just how the foundation will afford the empty mansion. If all goes well, and at least some of the tax penalties are forgiven, the 21,666-square-foot Bellosguardo soon will be filled not only with art, furniture, and Clark’s fabulous collection of dolls but also with visitors.

While the city’s idiosyncratic benefactor was still alive, people were the single element Bellosguardo most conspicuously lacked; now, with the stroke of a pen, all of the nothing that went on in Bellosguardo for so many years is history. Clark’s legacy will deliver one of the last undivided great estates in Santa Barbara to the public for its enjoyment and edification. Under the foundation, the estate looks poised to become, like Lotusland and the nearby Music Academy, one of the city’s truly distinctive attractions.

The Senator’s Shy Daughter

Fortunately, although the generous woman in question was exceedingly hard to get to know while she was alive, Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr.’s new book makes her more available now than she has ever been. The story in Empty Mansions spans nearly two centuries and begins with the man that the Clarks still call “the Senator,” even though he was persuaded to resign from that office the first time he earned it after accusations were made of voter fraud. William Andrews Clark, or W.A., as he was also known, was the copper king of Montana and built a railroad from the mines there through to Los Angeles at a time when none of the other railroad barons were willing to take that particular risk. Along the way, he founded a little junction town in Nevada called Las Vegas and married twice, the second time to Anna LaChapelle, who was young enough to be W.A. Clark’s granddaughter when their children, Andrée and Huguette, were born.

Born in the small Michigan town of Red Jacket in 1878, Anna LaChapelle was discovered in Butte by the copper king and received an education in French and lessons on the harp thanks to her wealthy mentor. Living in W.A. Clark’s apartment on Avenue Victor-Hugo in Paris as a teenager, Anna developed the tastes and opinions that would mold the estate at Bellosguardo, which was always, even after her death, considered her house. Anna, Huguette, and Andrée (for whom the Bird Refuge is named) came to Santa Barbara fairly often through the 1920s and 1930s, and, to the extent that she led any kind of public life as an adult, Huguette did so in Santa Barbara. For instance, she got married here in 1928 in a private ceremony that was nevertheless covered extensively in both the local and the national press. Huguette’s husband, William Gower, was a Princeton grad and the son of W.A. Clark’s top accountant.

But Huguette could not be a wife to Bill Gower and was separated from him before the year was out and divorced by 1930. She then resumed her maiden name of Clark while retaining the married title of Mrs. or Madame. Although the failure of her marriage may have had an impact on her desire to spend time in Santa Barbara, it was the deaths of both her sister and her mother that seemed to have pushed Huguette definitively into self-isolation. The sense that Bellosguardo was not a safe place first took hold during the early years of World War II, when the mansion’s exposed position on the bluff was considered vulnerable to a potential Japanese attack. After installing blackout shades and crossing the barbed wire that had been laid on Cabrillo Boulevard in anticipation of an invasion, Huguette and Anna moved to Rancho Alegre, a property that Anna acquired in Santa Ynez and that has since been given to the Boy Scouts. Even after the war, mother and daughter often stayed at the nearby Biltmore rather than opening the house for their Santa Barbara visits.

Although Huguette’s shyness had a role in her increasingly insular lifestyle, clearly a sense of fear was in play, as well. Having enjoyed many trips to the continent as a young woman, she later admitted that she was afraid to return to France in case of a second French Revolution. In later life, Huguette focused her energy on building and maintaining a variety of projects, including collections of paintings, jewelry, musical instruments, dolls, and even videotapes of animated cartoons. She may have owned a few Stradivarius violins, but that didn’t stop her from enjoying the Smurfs. Involved almost exclusively through intermediaries with complex negotiations over the construction of thousands of elaborate dollhouses, Clark developed her already formidable memory into something more tenacious and exacting. Even after turning 100, she knew by heart where all her things were stored.

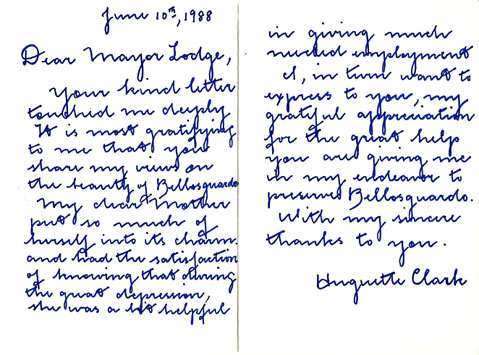

Jim Hurley, her lawyer in Santa Barbara, recognized Clark’s dedication and tenacity long ago. “I first recommended that she set up something like what Madame Walska did with Lotusland as far back as 20 years ago” he said, “and though I don’t know the details of how her final decision to create the foundation came about, I can say that she has always been generous to the city, not only with the Bird Refuge, but also with helping pay for the abatement of the odor there some years ago. Even though she didn’t come out here, I know that she was in constant contact with John Douglas, the caretaker, and that she intended to preserve and protect the property. She’s been extraordinarily generous to Santa Barbara, and while she was alive, we did what we could to protect her privacy.”

The Investigation and the Empty Mansions Book

Journalist Bill Dedman first became interested in Huguette Clark through another one of her empty mansions, Le Beau Château, which he noticed when scanning the real-estate listings. At the time, it was listed for sale at the highest price then being asked for any property in the state of Connecticut. He found that virtually everything about the Château’s owner was mysterious, from the pronunciation of her name to why she had paid to maintain an entirely unfurnished estate in tony New Canaan. When Dedman first wrote about the case for msnbc.com, thousands of emails poured in from readers wanting to know more. It was at this time that Dedman became aware of the fact that questions were being raised about the men who managed Huguette Clark’s money. Her accountant was a felon and a registered sex offender, and her New York lawyer had a record of benefiting substantially from the will of someone he had represented, a serious breach of fiduciary duty. “It was at that point, when it came out that both the attorney and the accountant had already once inherited from another client, that it tipped over into a criminal investigation,” Dedman told me. “The nurse, Hadassah Peri, had already received millions in gifts, also raising a lot of questions. The way I saw, it was, “It’s smoke; let’s see if there’s fire.”

That’s when Dedman met Paul Clark Newell Jr., a cousin of Huguette’s who had managed to get closer to her than nearly anyone, albeit almost entirely by telephone. Newell’s father died while working on a book about Huguette’s father, and there was already a substantial archive established by that effort. In Dedman’s effort to understand what Huguette’s life had been like, the approximately 50 conversations that Paul Clark Newell Jr. had recorded with her were a great windfall. “Their conversations, which we have included with the audiobook, filled in some of the gaps,” said Dedman. With the help of Newell’s evidence and firsthand knowledge, Dedman was able to begin forming a stronger impression of who this woman actually was, rather than having to accept what other people said about her.

This last is a crucial point with Dedman, and one he emphasized in our recent conversation about the book and about Huguette Clark. When I observed that he is scrupulously reticent when it comes to speculating about Huguette’s motives, he agreed and added the following self-description: “By practice and temperament, I maintain distance. For example, I don’t write about what people ‘believe.’ People lie, people posture, and people often give one reason for something they’ve done when they actually have another. It can be tempting to create dialogue, but I won’t, and it’s for the same reason that you won’t find me writing that someone is a devout Christian. The outward signs may be there, but if you aren’t that person, there’s no way you can be certain.”

Dedman’s objective attitude becomes particularly important later on in the book, when predatory figures surround Huguette, each peddling some version of her that forwards their cause. I found it hard to continue with the narrative at times, not because I wasn’t interested, but because I found Huguette annoying, especially as she became more reclusive. Dedman, who was aware of this possibility, nevertheless chose to leave it up to the reader to decide what to make of his subject. “I assume readers are smart,” he said, “and if you give them facts, they will think good thoughts. I don’t know why she liked dolls so much or what she found so interesting about the Smurfs. But I can say with certainty that this woman, who was trained as an artist, knew a great deal about animation and that she liked fairytales of all kinds very much.”

But what about the difficulties that many readers may have with accepting the extravagant wastefulness that is so apparent in the book’s main title, Empty Mansions? Won’t people need a way to think about all the resources Huguette Clark marshaled that were never used? “Well, we pushed and pulled at the examples to pair instances of her extravagance with instances of her generosity. On one page she will be spending $400,000 to have copies made of her mother’s old furniture, and on the next she’ll be sending $30,000 to a stranger or paying for the health care of the daughter of a former governess.”

According to Dedman, reversals of sympathy are built into the structure of the book even before Huguette comes on the scene. “The reader may decide that he or she likes W.A. Clark while he is still in his early years as a businessman, and then hit the scandals that arose in relation to his political career and decide that the Senator was not such a great man after all,” he said. “I didn’t write the book to correct people’s perceptions of these figures; I wrote it to present as best I could the known facts about their lives.”

Ultimately, the book’s greatest achievement — even more impressive than the massive amount of research and organization it required — may be precisely this reluctance to judge. Dedman offered a personal analogy by way of explaining his adherence to a code of strict objectivity. “While I was working on this book, my grandmother died in Tennessee, and I went down there to clean her house. In her attic, I went through all sorts of things, some dating from as far back as World War I. There were love letters, hats, and even a ledger book that she used to track the money she saved. She tried to save enough so that she could buy one nice new piece of furniture per year. I don’t know that there were any family secrets, but even the old LIFE magazines with her mailing labels said something to me. And then, after meeting Paul, it became much more real to me that this woman was part of someone’s family. And you know, you can learn quite a bit about someone from looking at their checkbook!”

As the Bellosguardo Foundation begins its work of building a public institution around this extraordinary legacy, the board will do well to heed the wise path already marked out by Dedman and Newell’s sophisticated, yet reticent approach. As Dedman writes in the epilogue to Empty Mansions, even though Huguette Clark may have preferred to live the final decades of her life “in a hospital room, with her hollandaise and brioche and cashmere sweaters,” she had the “courage … to be an artist at a time when that wasn’t an approved path for a woman, to break away from a marriage that she didn’t want, to resist the manipulations of her hospital and her museum to get more of her money, [and] to leave most of her estate to her friends and a charity that honored her mother’s memory.” Whether or not Huguette Clark truly did lead “a life of integrity,” as this final chapter claims, her story and her legacy Bellosguardo are with us yet, the former already open for discussion and contemplation, and the latter, one day soon, open for visitors and a new public life.

4•1•1

Authors Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr. will give a talk and sign books Sunday, October 6, 5 p.m., and Monday, October 7, 11 a.m., at the S.B. Historical Museum (136 E. De la Guerra St.). For more information, call 966-1601 or visit santabarbaramuseum.com/events.html. Empty Mansions is available at area bookstores.