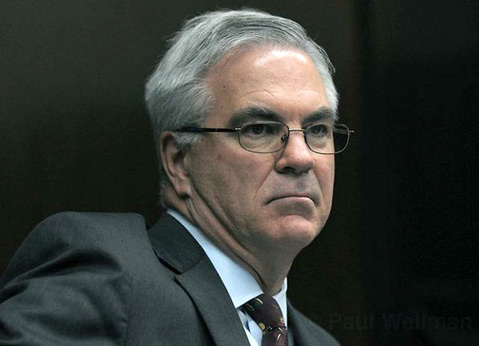

City Exec Jim Armstrong to Retire

With This Week’s News, a Major Leadership Makeover is Almost Complete at City Hall

Jim Armstrong, the chief executive who for the past 14 years kept the City of Santa Barbara’s oars firmly in the water while simultaneously keeping City Hall from running off the rails economically and politically, has announced he will retire three months hence. Armstrong’s announcement — which did not come as a surprise — brings to a conclusion the major leadership transformation sweeping City Hall in the past half-year with the key exception of the Chief of Police. Chief Cam Sanchez has indicated he has no intention of doing anything but staying put.

Armstrong was hired in September 2001 just before 9/11 and quickly found himself forced to weather the subsequent economic crash — as well as the dot-com implosion — it sparked. That turbulence, however, was nothing compared to the Great Recession of 2007, during which Armstrong put City Hall on a steady and early diet of budget cuts and service reductions. Although 100 positions were lost, only one person, Armstrong said, actually lost their job, a fact in which he still takes great pride.

At the same time, Armstrong found himself at the helm when the California Supreme Court abolished all redevelopment agencies throughout the state. This eliminated one of City Hall’s traditional funding sources for downtown revitalization, not to mention affordable housing. Afterward, when the state appeared poised to seize possession of the many parking lots and garages built over the years with redevelopment dollars, Armstrong teamed up with Mayor Helene Schneider to wage a successful lobbying campaign in Sacramento so that City Hall retained ownership and control.

When Armstrong started, the City Council was dominated by a liberal Democratic majority with strong activist inclinations. Five years ago, a Texas real estate billionaire with local ties spent nearly a million dollars to elect a conservative council majority, and for one year, he managed to achieve just that. Since then, moderate and liberal Democrats have managed to secure their traditional advantage, but only just barely. With the council in relative balance, both sides struggled over a years-long effort to rewrite the city’s general plan in hopes of promoting the mutually exclusive goals of neighborhood preservation and affordable housing. Throughout it all, Armstrong exerted a powerful behind-the-scenes presence. In person, he proved far more congenial and approachable than his predecessors, but when it came to policy, he proved far more restrained. That, he stressed, was the domain of council.

Still, in ways large and small, his influence has been profound. It was Armstrong, for example, who single-handedly wielded the authority needed to approve major changes to the plans for the long-festering La Entrada project. And it was Armstrong who crow-barred major contract concessions from the public safety unions so that police and firefighters now pay significantly more into their retirement accounts than they had before.

Through the years, Armstrong and the Police Officers Association have waged war in public, with Armstrong holding the line on hiring more cops and citing the $150,000 a year it costs to field one position. The union, in turn, has been quick to accuse Armstrong of putting the public’s safety at risk and exaggerating the city’s fiscal distress to keep from hiring more officers. That battle, always a City Hall perennial, shows little sign of abating. Two weeks ago, the council appeared ready to spend $150,000 to hire multiple rent-a-cops to patrol State Street. Such an expenditure would be a first for City Hall and could not have gotten so far without Armstrong’s tacit support.

Armstrong expressed satisfaction in getting a new airport terminal built, the Carrillo Recreation Center rebuilt, and the Cabrillo Art Pavilion on track for a major face-lift. He expressed regret he didn’t accomplish more in making infrastructure replacement a greater priority and securing a new funding source for such projects, like building a new police headquarters.

But with State Street crawling with shoppers, City Hall’s finances are much improved. After promoting or hiring new leaders for key city departments, Armstrong said, he felt it was time he made his exit. He won’t miss the bruising labor negotiations, the “crazies” who testify before the City Council, or the inordinately long time it takes to get anything done. But, Armstrong said, he will miss the people and he will miss the mission. “It’s time,” he explained. “I’ve been working at least 20 hours a week since I was 14. I’ve been a city manager since I was 29.”