Lynda Barry and Matt Groening Talk Love, Hate & Comics

Lynda Weinman Interviews College Pals about Creativity, Inspiration

Some of you may know me as Lynda, the co-founder of lynda.com, the website where you can learn digital skills, and the season sponsor of UCSB’s Arts & Lectures. What you might not know is that I went to college with The Simpsons creator Matt Groening and cartoonist/author Lynda Barry and that we’ve all been friends for well over 40 years. In anticipation of Matt and Lynda’s upcoming talk, Love, Hate & Comics: The Friendship That Would Not Die, I spoke with them both about their shared history and long-lasting relationship as two of the funniest and most unapologetic frenemies I’ve ever known. Together, their improv will make you laugh, cry, and long to live your life in its most creative mind-set.

Lynda Barry

The title of your talk is Love, Hate & Comics: The Friendship That Would Not Die. I get the “love” part and the “comics” part, but why “hate”? The hate part is what happens when you’ve been friends with someone for so long. From the beginning, our friendship has had a lot of hate in it. [Laughs.] I actually think that hatred has been given a bad name — there are certain times that hate is very natural. I was thinking about how much I love Matt and how much I hate Matt and how to me now he’s blood, he’s family, he’s cousin Matt — there’s no splitting up at this point. I mean, even if we don’t speak to each other for a few years, there’s no splitting up — he’s like my tattoo, and I’m his. I don’t even think he knows that, but it’s like there’s a picture of Marla tattooed on his back, and I have Binky tattooed on mine.

Has his work had any influence on yours? His work has had an influence, but I’d say his mind has influenced me even more. The way Matt approaches the world, the way that he always seems to be after something, how he can find the funniest things in anything … when he’s in a good mood! When he’s in a bad mood, it’s raining on everyone at all times. If he’s in a good mood, he can see the most hilarious beautiful things, so it’s his approach and excitement that has a huge influence. He’s also brilliant. Years pass where we won’t talk, but it’s like he’s always in my head, and his way of looking at the world has always had a big influence on me. It’s his mind that is so badass and hilarious.

Was it your idea to do these stage collaborations? Hard to remember. I feel like maybe I’m the little bait that they put on the trap to get Matt to come speak, like the cheese to trap the mouse. I don’t mind that, because I always felt that once The Simpsons hit, Matt’s work as an alternative weekly cartoonist has been downplayed, and he’s certainly not included in that part of the history of alternative comics. It’s almost as if his success with The Simpsons means that he’s not qualified any more to be considered alternative. When I edited the book The Best American Comics I really wanted to include him, and I got a lot of pushback from my editors. Just that year, he had published Will and Abe, which I always loved, so I included those.

Speaking together seemed like a great excuse to get together. We really like to see each other, and we live on opposite ends of the country, so we’ve gotten together to do these talks in Providence, Rhode Island, Madison, Wisconsin, and in India! It began with this whole thing of wanting to include him in what I feel that he’s been unfairly written out of.

You met in college in 1975. Has your relationship changed over the years? It’s still the same relationship: completely based on wanting to irritate the other one. When he took over the editorship of our college paper, he made a proclamation that he would print anything that anyone submitted. I remember thinking, really? It became my joy to try to find something that he would not print. I began by writing fake letters to the editor, outraged about things that happened to me when I was nine. He printed those. I wrote really crazy shit, like how the media department at our college was now checking out guns, and I was complaining about that. And he published that when of course they weren’t. Then I started making comics that I thought were way too far out to print, but he printed everything. And that was how it started. He was a year older than me at school, and I didn’t understand him at all. I thought he listened to musak, but it was Nino Rota [Fellini’s music composer]. But to me, when I heard it, I thought, ‘Why is this dude listening to musak?’ He was at a hippie school, but he hated hippies. I don’t know if you remember this, but he wore shirts with buttons and shoes with laces.

I thought I could free him, not understanding that he was so free that he was already wearing the shit that would drive all the hippies crazy. I remember looking at him and thinking, ‘This kid needs to be loosened up.’ Like, right. I just didn’t get it. We have differing memories of how we interacted. My memory is that he was always trying to ditch me.

I started writing for him when he was editor of the school paper, so he gave me my first journalism assignment: Taste the best hamburger in Olympia. I think he called it “Burgers on Parade.” I didn’t want to tell him that I was vegetarian, so I ate 10 hamburgers in 48 hours and they were all really good! [Laughs.]

So, were you already cartooning before you were contributing to the school paper? I always drew. I never stopped drawing, and in high school I would draw a comic strip and had a friend who would do the captions. But I discovered my voice when I had to make comics that I wanted someone not to print. One of the comics was an argument between two men, and one of them didn’t have any legs, and the other was an asshole. They were arguing over which was worse, to be an asshole or not to have any legs. And [Matt] printed that.

Then I did one about a little girl who had one of those fathers who was always reading the newspaper and not paying attention to his little daughter, and he asked her what she learned in school without looking at her. Her arms and legs dropped off so she was just a torso. Matt printed that. I did one with a spatula singing to some eggs in a frying pan, “I Put a Spell on You.” I kept really trying to make something that would make him go “Hell, no.” I just never could hit that button. He always printed everything.

I only found out that Matt wanted to be a cartoonist when he came to Madison to visit my class. For a lot of his life, he had studied cartoons and animation, and when he taught my class, I learned new things about him. There he was in front of my class being one of the best teachers. He talked about the power of silhouette and showed how with the Simpsons characters, that from their eyes up — even from their eyebrows up — you can tell who each of the characters are. He showed us all his drawing styles, and then he had us draw self-portraits in every one of his drawing styles, which was hilarious. I was so surprised that he’s a really good teacher. Which is a terrible thing to say, isn’t it? [Laughs.]

It makes sense, though. That’s a good segue into your latest book and the fact that you are doing so much teaching now. Has it been a transition from being an artist and a writer and a cartoonist into being a teacher, or is it all just the same thing to you? The state of mind that I have when I’m teaching is identical to the one that I have when I’m making a comic or writing a novel or working on a play. And that goes right back to Evergreen. That’s the thing that you and I and Matt all have in common. It’s just learning this certain way of being.

I’ve been chasing this question that that Marilyn Frasca [a teacher at Evergreen] asked me when I was 19: “What is an image?” It’s coming on 40 years that I’ve been trying to answer this question, and I got to the point where I realized that I’ve gotten as far as I could with that question in my own practice.

The longest workshops that I ever taught had lasted at the most for five days. I really longed to work with people at different stages of their relationship to drawing and writing, from people who feel very comfortable doing it to ones that have great longing but had stopped when they were maybe 10 years old. I applied to be an artist-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and they were going to give me one class for one semester. After that, I was just hooked. I had an experience with my students where I could see how images moved through the individual and how they moved through a classroom. I could see the transformation that people underwent, particularly those who felt in the beginning that they were in a deficit because they stopped drawing when they were younger only to find out that their route into a very original and creative line was much quicker because of their drawing when they were young. Their drawing style, or lack thereof, was intact. Observing this process was just fascinating to me and inspired my interest in teaching.

I teach a class called “Draw Bridge” with 12 PhD students at the point of writing their dissertation. I’ve been able to design a class where they team up with 4-year4olds — not to draw, but as co-researchers. A brilliant student named Ebony Summers figured out how to transform my method of creative and autobiographical writing so that you can use it for academic papers. It’s just amazing how it still maintains this odd element of fun! I also teach comics. You would think that after being a cartoonist for so long I would have taught earlier in my career, but I was always really nervous about it, and now I feel very comfortable.

Half of my teaching appointment is with the art department, and the other half is with this amazing institute called the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery. It’s filled with physicists, mathematicians, geneticists, bacteriologists, virologists — all these scientists working together. I have a lab with all of these brilliant, brilliant people — all of them want to draw. I’m driven to know more about what compels these accomplished, brilliant people to have this longing to be creative.

I’ve discovered that there are things that almost always happen when somebody comes to my lab to draw. At the end of the two-hour drawing session, they all say it’s been forever since they’ve taken that kind of time to make a picture. They also couldn’t assess how long they had been there, and tell me how afterwards they feel physically better. Now that I’m at a university, I can study this stuff even if I don’t have the academic background to understand what is going on biologically when people are drawing. I work with the people who can. And that’s fucking amazing.

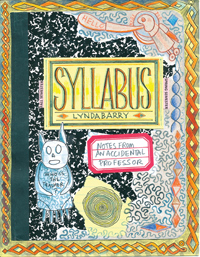

Tell me a little bit about your latest book. The name of the book is Syllabus, and it’s the notes that I kept during my first three years of being what I call an “accidental professor” at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. It includes the actual assignments that I gave my students and explains the process I went through trying to design different classes. There are also examples of student work. For example, I give them a pen and piece of 8.5” by 11” paper and I tell them they have two minutes to draw a house on fire. Then I ask them to spend time coloring it in. These astonishing pictures come together, and when you put together a whole classroom of different people with different drawing skills, where everybody spent only two minutes on the drawing part, and then quite a long time on the coloring-in part, you just see that there’s something magnificent about it.

The book explores this other kind of drawing that’s very different than representational drawing. It’s more akin to the drawing we did when we were little and learning the alphabet. The book looks like a dropped plate of spaghetti; every possible inch is covered with writing and drawing. Drawn & Quarterly did a beautiful job. The book looks and feels exactly like a composition notebook that we use in the class. So, physically, it’s a really sweet book.

That’s great. Will the book be available at your lecture? Yes!

Matt Groening

What’s it like to collaborate with Lynda Barry on a live show? One of the most fun things I have ever gotten to do is to share the stage with Lynda. We’re old friends, and I’m secretly her biggest fan. For me, being able to listen to Lynda talk about whatever is on her mind is always entertaining and funny and illuminating. And sitting with her onstage, I feel like I have the best seat in the house.

Tell us a little bit about your friendship with Lynda and what it means to you. I met Lynda at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, a small progressive school with no grades and no required courses. The student population was made up of every creative weirdo in the Pacific Northwest. And Lynda was one of them, and I was another. And you were another, except you weren’t from the Pacific Northwest! I think that the people who gravitated toward that school were just not interested in business as usual. At the time, the school was so new that it wasn’t even accredited yet, and the conventional wisdom said that we throwing our lives away by going to this crazy hippie college. I think that everybody there believed in the style of education so much that we knew that we weren’t going to make our livings with a college credential but rather that we were going to live by our wits. The school was full of people who felt that way. Then the school did get accredited, and so it became a fine place to be proud to have graduated from.

Lynda was a creative artist and a writer, and she ran the college art gallery. She once brought a hula dancer to Evergreen as an art performance, and in doing that she finally found a way to get under the skin of the gentle hippies. [Laughs.] There was some uproar about whether or not hula dancing was an art, and of course it was. Lynda was ahead of her time.

She was also one of the great cartoonists, even back in college. At the time, she did little scratchy comic strips that I thought were hilarious, and I liked drawing cartoons, as well. I don’t know if we influenced each other so much as far as content goes; we just both liked the idea of making comics.

After graduation, she headed to Seattle, I headed to Los Angeles, and we both continued to do comic strips, which for both of us turned into weekly comic strips in the alternative newsweeklies around the country, and books. We had parallel careers, and we stayed in touch with each other all those years. We used to stay up late on the phone while we were inking our strips to keep each other company.

Has her work influenced yours, would you say? What I like about Lynda is that she follows her passion wherever it goes, and whatever she’s working on pushes her into areas of risk and uncertainty. I find that very inspiring. She’s done such a huge variety of work, but at its core, I think it’s very personal, very pro-individual, and tries to give voice to people who are usually overlooked, like with her stories of children and people who are struggling.

On top of that, she is one of the funniest people I’ve ever met, and she always makes me laugh.

Do you think your work has influenced her? [Laughs] I doubt it! I think she thinks that I am appalled by her life choices. She lives on a farm in Wisconsin. I know she can’t believe the choices I’ve made living in L.A. and working in Hollywood. She would not put up with the stuff that I put up with and tells me so. Maybe I provide some anti-example for her.

Do you think you’ve changed, or are you the same people when you met in college? In a way, I get the feeling that no matter how things turned out, or how people responded to our work, we’d still be doing the same things. That creative spark would continue, and we would still be drawing comics and making up stories and whatever. It’s been great that it’s worked out. Lynda has created a ton of books that I think are going to stand the test of time, and there are people like me who can’t wait to see the next thing that she comes up with. Her work is so friendly and encouraging that when you read something by Lynda, no matter what, you feel better afterwards.

What do you hope that people get out of seeing the two of you? We really have fun with it and with each other. We trip each other up a little bit with some things that the other person doesn’t expect, so there will be a little bit of that. I think she does a little bit more to me. I’m more of the straight man to Lynda’s wild improvisations. But I’ll get in my punches. [Laughs.]

We read aloud, we perform some comic strips for the audience, we’ll talk about our friendship and some of the funny stuff that happens. We’ll share some embarrassing photos from our past, and then we’ll talk about creativity. The rest is up for grabs. I guarantee the audience will be diverted.

One important last question. Where do you like to eat in Santa Barbara? They are all taquerías: La Super-Rica, the most famous place; Lilly’s; La Colmena; and Los Agaves. Three of those are right on Milpas, which is the most magical street in all of Santa Barbara!

411:

UCSB Arts & Lectures and 88.7 KCRW present Lynda Barry and Matt Groening, Love, Hate & Comics: The Friendship That Would Not Die at the Arlington Theatre (1317 State St.) on Friday, October 10, at 8 p.m. For tickets and info, call (805) 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu.