In from the Cold

Former Foes Join Forces on Milpas Street to Help Chronically Homeless

It’s not exactly the lion and the lamb lying down together in the manger, but by Santa Barbara standards it’s the next best thing. When Marcos Olivarez first encountered Sharon Byrne of the Milpas Community Association, it was not under the best of terms. “I hated her,” recalled Olivarez, an otherwise soft-spoken native of Santa Barbara’s Eastside.

At the time, Olivarez had been on the streets for many years. Having just been given the boot by the Casa Esperanza homeless center — where he’d worked for two years — Olivarez made it his life’s mission to torment shelter operators as much as possible. It turned out he possessed a singular talent for doing so. Olivarez, now 55, emerged as the charismatic ringleader of an unruly crew of determined hell-raisers who planted themselves daily in front of the Casa. Alcohol and drugs were very much involved. Shouting and arguing common. Fights frequently ensued. “I was their biggest headache,” he said.

About three years ago, Byrne — tough, street smart, and politically brash — had already emerged as a force to be reckoned with on the Eastside. She was also in the midst of a campaign for City Council. Byrne concluded Olivarez had become an intolerable nuisance, and in a face-to-face confrontation, she told him he had to go. He told her to go to hell. “This was my home,” he said.

Byrne responded by twisting arms at the seven liquor stores surrounding the shelter. Don’t sell booze to Olivarez, she warned. They didn’t. She got in the face of work crews at the nearby Caltrans construction site where Olivarez slept. “Don’t you have a lock you can put on your fence to keep Marcos out?” she demanded. They got one. In this fashion, Byrne put a serious squeeze on the king of the Milpas Street troublemakers. At the time, Olivarez wasn’t in great health. Byrne remembered him having yellow eyes and sour skin. Byrne offered to get Olivarez into detox and a bed at the Salvation Army. For three days, he resisted. Then he gave in. “I was tired,” he recalled. “I was killing myself.”

Since then, a whole lot has changed on Milpas Street. Former enemies have since become friends. Today, Olivarez and Byrne are working collaboratively on a pilot enterprise dubbed the Milpas Outreach Project, a hyper-local neighborhood effort getting the most stubbornly determined Milpas homeless into housing and then bombarding them with all the services needed to stay off the streets.

Olivarez now runs an organic, community garden project on the city’s lower Eastside, Pushing Shovels, where he helps a crew of 26 volunteers — individuals with mental health and addiction issues — cultivate an array of vegetables, including four types of kale. For this he receives a small stipend from a grant Byrne helped him write. Olivarez, who studied horticulture in high school and briefly belonged to Future Farmers of America, is endowed with an exceptionally green thumb. And thanks to the Outreach Project, for which he works as one of two peer counselors, Olivarez now has an apartment in the affordable housing complex El Carrillo. His kids, he said, no longer have to nag him about getting a roof over his head.

By any reckoning, Olivarez qualifies as a screaming success story. He’s housed. He’s working. He’s making money. And his outreach work to others still on Milpas Street has proved invaluable. But even so, it took nearly half a year to secure Olivarez housing. Since then, Olivarez has experienced a few hiccups. El Carrillo is known for its strict visitation rules, and Olivarez’s experience demonstrates why. On the way out, one of Olivarez’s recent visitors stopped in the community room at El Carrillo and smashed a phone and then urinated on the floor. Olivarez was held responsible. One more slip and his housing could be in jeopardy.

Red-Tape Ninjas

Statistically speaking, the Milpas Outreach Project is a modest success. Of the individuals initially targeted, six have been housed, one has died, and about four more remain on a cosmic to-do list. Two months remain to meet the task force’s initial goal of getting 10 people housed and off the streets in year one.

But statistics don’t tell the whole story. That the outreach project ever got off the ground qualifies as one of the more improbable achievements in the annals of Santa Barbara grassroots community organizing. Joined together in common purpose are former homeless rabble-rousers such as Olivarez, die-hard advocates for homeless rights and the homeless shelter, and neighborhood organizers such as Byrne, who for years complained that the Casa Esperanza generated a crime wave of public urination, panhandling, and intoxication that transformed lower Milpas into a scene from Night of the Living Dead.

Two years ago, many of these same players could barely stand to be in the same room. Now every Tuesday morning, they meet at Casa Esperanza for one no-nonsense hour. Fourteen experienced, tenacious, inventive, bureaucratically savvy red-tape warriors — representing a smorgasbord of nonprofits, government agencies, Milpas Street business interests, mental-health professionals, veterans representatives, and former street people — sit around a long table discussing how to bring in from the cold a handful of regulars deemed most likely to die if they remain where they are.

It’s anything but easy. If educated, affluent individuals lucky enough to have health insurance find themselves driven past the breaking point trying to access care, imagine how difficult it must be for longtime street people seeking to navigate the bureaucratic maze of mental-health care, public health, and social services. How do they seek jobs without a birth certificate, a driver’s license, or a Social Security card? How do they apply for housing with no rental history?

Weekly, the members of the Milpas Outreach Project assemble to overcome these nuts-and-bolts challenges. Specific jobs are assigned. Who is driving Mr. X to a psychological evaluation so he can get meds? Who is taking Mr. Y to a Veterans Administration office in Ventura to get his lapsed veterans housing vouchers reactivated? That’s the easy part.

Harder is establishing the human connection and building of trust to convince longtime Milpas Street regulars — a number with serious mental-health ailments — that they might actually want to change. For many, the street is the only life they know. As the Tuesday morning crew has learned, even when the answer is yes, it often reverts to no. Repeatedly. Setbacks vastly outnumber the successes, an inevitable fact of life. To keep going, victories — even the smallest — must be savored.

The motivation of the project’s participants varies. Some see chronic street people as a blight on business. Some find the revolving door between the streets, the jail, and the emergency rooms fiscally offensive. Others are do-gooders addicted to humanitarian causes. Some have painful personal experience with addiction and mental illness in their immediate families. And many are moved by religious faith, seeing their work as a manifestation of biblical teachings. But all of them recognize the current system isn’t connecting those in the greatest need to the services that are available. To turn that around, they’ve bet their own time, energy, and, in some cases, cash on a new way that stresses human-to-human contacts at the neighborhood level.

It’s too soon to say with any precision how much the effort has paid off, but had the six people housed since the program was first launched in February remained on the street, it’s certain they would have been the subject of countless law-enforcement actions, hauled off who knows how many times to county jail, and likewise dropped off at the hospital. Based on their previous histories — compiled for the group by the Santa Barbara Police Department’s Restorative Justice detail — the number of such incidents would be high and the dollar amounts even higher. All six were certified frequent flyers — known in the trade as “Million Dollar Murrays” — when it came to draining public resources. All had burned their bridges with area shelters, detox facilities, and most anyone who might be inclined to help.

The Way Back Machine

Santa Barbarans have been wrangling with the issue of homelessness almost nonstop since the 1980s. In 2000, the city mothers and fathers decided to open a winter shelter on Cacique Street by Milpas Street and the railroad tracks. As a fusion of altruism and commerce, the idea was a masterpiece. The Cacique Street shelter — dubbed Casa Esperanza — would keep disruptive and disturbing street people out of the central business district, while simultaneously providing a desperately needed respite from the cold and the rain. But as a coherent, sustainable service operation, Casa was always an overwhelming challenge.

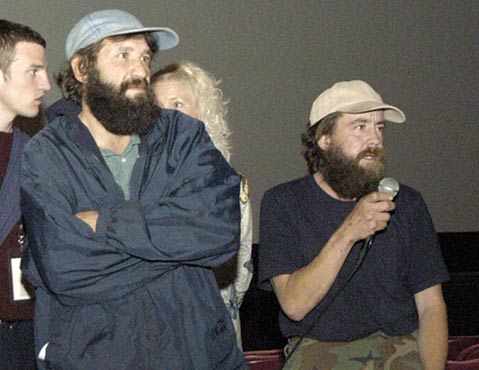

Even before its inception, David Hopkins (aka “Hopper”) argued at a public meeting that it was insanity to compress so many dysfunctional people with so many different problems — alcoholism, drug addiction, and mental illness, to name just a few — under one roof. But Hopkins, who would amass a record of 487 open-container citations during his years on the street and be brought back from death twice, was pretty drunk at the time — and, by his own admission, pretty obnoxious, too. John Jostes, who facilitated that meeting, still gets hot remembering having to yank Hopkins out of that assembly. Since then, Hopkins has cleaned up his act and, along with Olivarez, is a peer counselor with the Milpas Outreach Project.

In response to the ancillary impacts associated with Casa, a group of Milpas Street business owners and residents formed the Milpas Community Association (MCA) about four years ago. Their chief beef, ironically, carried echoes of Hopkins’s drunken critique. MCA members decried Casa Esperanza as a malignant public nuisance — a magnet for ne’er-do-wells nationwide — foisted unfairly upon an unsuspecting lower Eastside. It was bad for business and bad for the neighborhood. Leading the charge were Sharon Byrne and Alan Bleecker, owner of Capitol Hardware.

In October 2010, the city’s planning commission held a lengthy hearing. Jostes — who then was a planning commissioner — described it as “Bad Behavior Day.” Both sides railed against the other. MCA advocates blamed city officials and demanded relief. Homeless-rights advocates — including a group of ministers who showed up early to pray on the City Hall steps for the souls of Byrne and Bleecker — wagged their fingers in moral disapproval at the MCA. It was ugly.

In 2012, MCA filed a formal challenge with City Hall, contending that Casa Esperanza had become an ongoing violation of its conditional-use permit. Something, they demanded, needed to be done.

In the end, City Hall concluded Casa Esperanza was in compliance with its permit. But only just barely.

City administrators ordered the reactivation of the quasi-dormant Milpas Action Task Force as a forum to hash out shelter-related issues. And Jostes, with mediation ranking among his many professional skills, was hired to settle this hash. It was among his most difficult assignments. Likening the early meetings to a “family jihad,” Jostes said the warring camps “dealt with differences as battles to be won, not problems to be solved.” It got so intense that he had to threaten to quit several times before basic rules of conduct could be agreed to.

Successful mediation, Jostes explained, depends on “preparation, skill, attitude, and luck.” In this case, he said, “luck” struck in the personage of Jeff Shaffer, a decidedly low-key, get-things-done homeless advocate associated with Casa Esperanza. Shaffer was also a minister. In fact, he was one of the ministers who prayed for the souls of Byrne and Bleecker before the October 2012 planning commission hearing.

Most people involved now agree that without Shaffer, the Task Force talks would likely have degenerated into World War III. Some people are natural talkers; Shaffer’s a natural listener. His gift is hearing what’s behind the words, not just the anger propelling them. Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider said of Shaffer’s importance to the project, “He’s the glue.” Byrne, who recalls with sardonic edge Shaffer’s role at the pray-in, gushed, “His sense of smell for what people can and can’t do is very, very good. He’s excellent at reading hearts.”

The renewed Task Force talks took place, just as the constellation of rules, regulations, and organizations involved with homelessness in general — and on Milpas Street in particular — was undergoing a massive upheaval. In 2010, Shaffer helped lead the first of two countywide homeless counts, enlisting for the effort a record number of 500 trained volunteers. (They found there are roughly 4,000 homeless; a third count is scheduled for this January.) He has since taken a leadership role with the latest über-entity — the Central Coast Collaborative on Homelessness — that sprouted up to wrestle with the Rubik’s Cube of homelessness. City police set aside two full-time cops to function as social workers with badges and guns to ensure street people got connected to necessary services.

In that same window of time, Casa itself experienced a profound financial implosion, leading to a wholesale changing of its guard. As part of that reorganization, Casa adopted new rules last year, limiting admittance to people who can prove both their sobriety and their residency in Santa Barbara County for at least six months.

The aforementioned changes explain how Jeff Shaffer got a positive reception when he asked MCA’s Sharon Byrne out to coffee at the Milpas Street McDonald’s a little more than a year ago. With the new Casa rules, there were fewer street people on Milpas, and the MCA’s level of agitation had dropped accordingly. Even so, Byrne was wary. Shaffer, after all, was one of “them.” Over coffee, Shaffer made it clear his goal was to get homeless people off the street. “He wasn’t all about letting the homeless stay homeless,” Byrne said. “That’s when I knew we could work together.”

Forming the new outreach effort were many of the usual suspects — representatives from the Housing Authority, county mental health, social services, Common Ground, and Casa Esperanza. There were a couple of philanthropic-minded former business executives with Social Venture Partners looking to lend a little cash and a lot of entrepreneurial insight. Keeping it all humming is a young former Coast Guard medic named Luke Barrett, who volunteers for Doctors Without Walls. Giving these good intentions the grit needed to connect with hard cases are David Hopkins and Marcos Olivarez.

miserable.

Loving Tough

Aside from Byrne, the most surprising player to jump in has been Alan Bleecker of Capitol Hardware. In years past, Bleecker seethed like a blast furnace over problems associated with the homeless shelter and, even more, City Hall’s refusal to understand. The angrier he got, the less City Hall “got” it. In hindsight, Bleecker said he understands now how off-putting he was. “I was a bit of a jerk,” he said at a City Council meeting a month ago. In the past few years, the Bleecker family was forced by circumstances to endure personal challenges that opened his eyes (and heart) to some of the realities confronting people on the street. Today, Bleecker remains every bit as tough as he’s always been but rounding out his approach is something new: love.

When it comes to “tough love,” Bleecker walks the walk. Not content merely to exhort people to change, he sought out one of Milpas Street’s most chronic offenders, offering to pay for a three-week detox. “I tried to get him to remember a better time in his life,” Bleecker recalled. “I offered to help him get there.” It would take more than that. Bleecker bird-dogged the man in question, who, it turns out, sustained a head injury in 1974 while serving in the marines in Japan. Bleecker took multiple photographs of the man inebriated on the street and delivered them to the Milpas liquor stores. Like Byrne, he exhorted the clerks not to sell.

Within the Tuesday morning crowd, this approach is not without controversy. Peer counselor Hopkins objected that Bleecker was invading the man’s privacy. “The streets are the guy’s living room,” he said. “How would you like someone taking pictures of you in your living room.” Bleecker said he got a letter from an attorney making the same point. He worried he might get sued. He didn’t.

Ultimately, Bleecker not only paid for the man’s detox but also offered him a job at the hardware store. A condition of employment has been sobriety, which Bleecker has enforced with the help of a Breathalyzer. There have been a few hiccups along the way, some serious. But Bleecker said the man remains one of his best employees.

Bleecker got another well-known frequent flyer into detox only after executing a citizen’s arrest on him for public urination. Again, he documented the offense using his cell-phone camera. Bleecker said it took the police 45 minutes to respond. “That was the 45 minutes I needed to get inside his head,” he said. In the past month, that individual moved into an apartment, his first time inside in years. Before that, Bleecker said, the man was so dirty that he left a brown stain mark on the wall where he perched behind the Chapala Market.

Bleecker, a deeply religious man, said he looks for emotional triggers to help convince people to make the change. In some cases, he has yet to find the right one, but he keeps trying. Last Wednesday night, Bleecker was at the Casa Esperanza until 7 p.m., pleading the case of a street person he’s been working with who “blew numbers” on the Casa’s Breathalyzer. Bleecker’s been working on this guy — another veteran — a long time now.

And housing is just the beginning, not the end. It marks a whole new way of life. It can be alien; some report getting lonely confined to the four walls, away from their crowd. They don’t know what to do with themselves. Those with jobs now have money and time. Some drink. For one elderly couple — inside for the first time in 16 years — the transition has been relatively smooth. The Tuesday morning crew checks on them once a week. Others require daily calls, lots of hand-holding, and many cups of coffee at McDonald’s.

The hope is that the Milpas pilot project will prove so successful that other neighborhoods will adopt their own variant. Already, Shaffer and Byrne have taken their show on the road to the Downtown Association, which represents State Street business interests. Byrne and Bleecker are also pushing for the creation of a business improvement district on Milpas Street. Among other things, it could help fund the outreach effort as an ongoing operation. But the new business district has a long way to go, and it’s already encountering blowback.

For Bleecker, it all starts with the first rule of shoe-leather organizing: human contact. “You have to get to know the people on the streets on a first-name basis,” he said. “We can’t rely on government. We can’t rely on social service organizations. We have to be there. With tough love.”

Getting people off the streets, he admitted, is hard, demanding, and complicated, akin to hoisting a wet mattress up three flights of stairs. “But when you get to the top, the mattress eventually dries out,” he said. “And someone gets to sleep on it.”