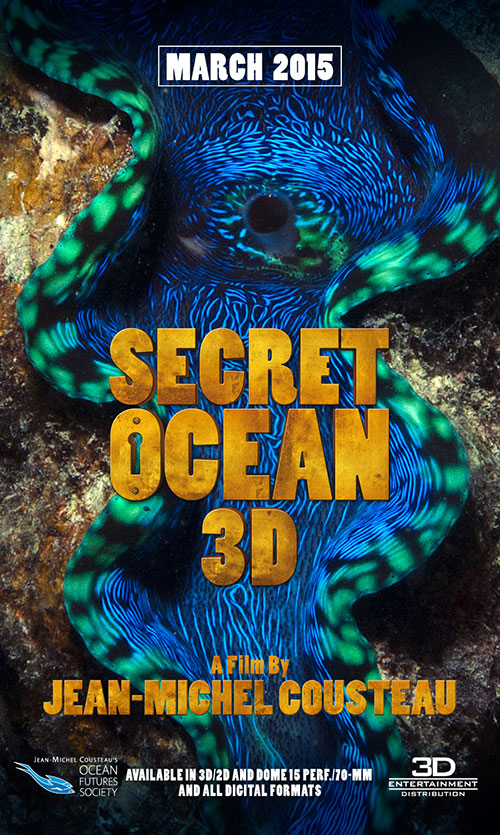

Secret Ocean 3D

All Sea Creatures Great and Small

Will the blue beings and the ethereal creatures sharing the otherworldly planet manage to ally themselves against a common enemy to survive? That could almost be the plot line of Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Secret Ocean 3D. But forget epic Avatar-style battles between alien species; for his directorial debut with a 3D film, Cousteau chose true romance. Nature, it seems, can be way weirder and infinitely more enchanting than science fiction.

Shot in Fiji, the Bahamas, and the Channel Islands, the mesmerizing 40-minute film, premiering at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival and opening at IMAX theaters in March, is an intimate study of sea creatures, from manta rays to the microscopic. By shedding light on their interrelatedness, Cousteau said, he hopes people will come to appreciate and fall in love with them — as wild animals — rather than seeing them as a food resource.

“I’ve always had only one mission,” explained the award-winning filmmaker and environmentalist, ever the son of fabled Aqua-Lung inventor and ocean adventurer Jacques. “Like my father said, ‘Protect the ocean, and we protect ourselves.’ People will protect what they love — but how can they protect what they don’t understand?”

Through Cousteau’s eyes — and the magic of producers Jean-Jacques and François Mantello’s large-format, macro-view 3D digital cameras — we’re introduced to a motley cast of characters, each in mind-boggling detail. Some may be familiar (lobsters, octopus, moray eels). Others, less so (arrow crabs, banded cleaner shrimp, sea hares).

In the film, Cousteau teams up on-camera with longtime colleague Holly Lohuis, a biologist with Ocean Futures Society, his conservation nonprofit in Santa Barbara. “I want to show you one of the strangest organisms I have ever seen,” rasps the scuba-masked Frenchman to his dive buddy on location in the Bahamas. Suited head to fin in matching blue wet suits and gear, they glide closer for a peek.

Et voilà: a basket star! A relative of the starfish, it looks like a yellow tumbleweed.

“It has no eyes, no blood, no head!” marvels an unseen narrator with a hint of glee. That would be the witty and erudite Sylvia Earle, famed oceanographer and explorer, whose voice-over underscores the film’s scientific and educational messages.

The basket star, we learn, does have a mouth. And a friend! The two animals that Cousteau and Lohuis peer at seem to be snoozing, entwined in corals growing on a shipwreck off New Providence. After sundown, one of them awakens and wanders off on its multiple arms in search of dinner.

The scene sets the bar for more intrigue to come: a pinkie-sized goby rooming with a blind shrimp; the dependencies of giant clams on zooxanthellae; a dance of pearlescent feather dusters and Christmas tree worms; the soft life of anemones and clownfish; the conundrum of involuntary invaders with big appetites; iridescent squid spawning en masse off Catalina Island; and a graceful tête-à-tête with nurse sharks and silvery hammerheads — all finessed by underwater cinematographer Gavin McKinney (his repertoire includes five Bond films).

“We filmed in slow motion, often at night, sometimes an unseen universe of organisms too small to be seen by the naked eye,” Cousteau said. “We had to create a whole new way of filming. It was fascinating to see the behavior and details of these creatures.”

What viewers won’t see, added ecologist Richard Murphy, Ocean Futures chief scientist and the field team’s still photographer, were the challenges of location filming in 3D while working from boats and beach huts. In Fiji, the currents were so fierce that the cameras had to be mounted on tripods anchored to the seafloor. In the Bahamas, the intrepid Mantello brothers attached the cameras to a 150-square-foot scaffolding cobbled together just to film the basket stars. To check footage shot in the morning meant afternoon downloads — terabyte by terabyte — to external hard drives. To view 3D snippets, the team took turns at a 19-inch TV monitor. From there, they just had to picture those snippets in continuity on a 90-foot-wide screen.

The result of all their seasoned skill and expertise looks effortless. We see that nature scales, that basket stars have a cuteness factor, and that the ocean’s wild animals are more dazzling than any motion-capture animation or computer rendering could ever be.

In 2009, a film critic lauded Avatar as director James Cameron’s understanding of “the value of gigantism and awesomeness.” Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Secret Ocean 3D draws on “gigantism and awesomeness” to show us the value of diversity and interdependence, the diminutive, and the commonplace.

4∙1∙1

Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Secret Ocean 3D premieres Wednesday, January 28, at 7 p.m., at the Arlington Theatre, when SBIFF presents the Attenborough Award for Excellence in Nature Filmmaking to Jean-Michel Cousteau and his son and daughter, Fabien and Céline. The film also plays Monday, February 2, at 8:10 a.m., at the Metro 4 Theatre. For tickets and information, visit sbiff.org.

More Cousteau Adventures: Swains Island

Another Jean-Michel Cousteau production, Swains Island: One of the Last Jewels of the Planet, reveals the wild beauty, ecology, culture, and history of a minute, seldom-visited atoll located 200 miles north of American Samoa in the South Pacific. Coproduced and filmed by Santa Barbaran Jim Knowlton — a diver and cameraman who launched his career with an internship at Ocean Futures Society — the documentary follows Cousteau, NOAA scientists, and other researchers as they survey the island. “As a filmmaker, it was an awesome opportunity,” says Knowlton. “You can only reach the island by boat, and we slept in tents on the beach.” Swains’ remoteness, he says, has helped shield it from many of the pressures that affect the rest of the world. The island gained protected status in 2012 as part of the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa.

Swains Island plays Wednesday, January 28, 4:20 p.m., at Metro 4 Theatre, and Tuesday, February 3, 1 p.m. at the S.B. Museum of Art. See sbiff.org.