Herd Immunity or Insanity?

Santa Barbara Anti-Vaxxers Tip the Scale

Public Health director Dr. Takashi Wada might not have known he was going into government affairs when he started med school, but now that he is entering his fifth year as head honcho of the county department, his job has become quite politically charged.

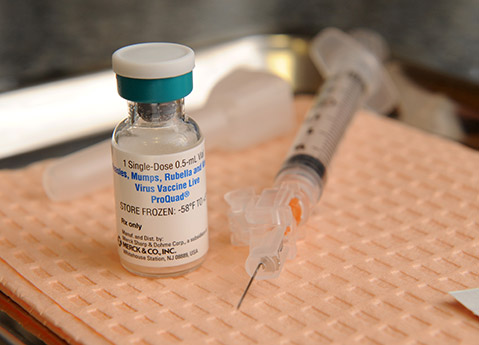

Driving the current debate around vaccinations is a recent outbreak of measles that originated at Disneyland in December and has infected 121 people in 17 states. No cases have been confirmed in Santa Barbara, but a number of false alarms and 11 cases in Ventura County have made health officials sweat, and for good reason.

Pockets of Santa Barbara County — typically affluent ones — have some of the highest vaccination opt-out rates in the state. Many parents are choosing to not fully vaccinate their children for “personal belief” reasons. Montecito Union School, for instance, had a 27.5 percent opt-out rate last school year. That’s triple the amount from 2007. Last year at Washington and Roosevelt elementary schools, 16 percent of parents filed exemption forms. At Monroe and Santa Barbara charter schools, 17 percent of children were not fully vaccinated. These numbers have reportedly stabilized or decreased somewhat this year.

Doctors say high exemption rates can be troublesome for communities because it effectively nullifies the benefits of herd immunity, which occurs when 90-95 percent of children have gotten their shots. A vaccinated child could still be vulnerable to diseases thought to be preventable — measles, pertussis, mumps, meningitis — as immunizations are not 100 percent effective. What’s more, herd immunity protects babies or a child with a medical condition who cannot handle vaccinations. Virtually all students at Franklin, Harding, and McKinley elementary schools have been vaccinated. The same is true for public elementary schools in Santa Maria.

Ever since the polio vaccine became mandatory for public and private school children in 1961, parents could file a “personal belief exemption” with the school nurse’s office. The catch is that if an outbreak occurs, unvaccinated children are banned from school in the Santa Barbara Unified district. On Monday night, Hope School District boardmembers voted to implement a similar ban if exposure to a disease occurs in their district. Earlier this year, an outbreak of pertussis, or whooping cough, occurred at the Waldorf preschool on Hope’s Vieja Valley campus. At Waldorf, 31 percent of children are not fully immunized against pertussis.

“By and large the people who chose not to immunize [in Santa Barbara] were very well versed and educated with regard to the pros and the cons,” said Dr. David Hernandez, who worked with a number of anti-vaxxers in his private practice 20 years ago. Often, he said, patients looked to homeopathic remedies and alternative ways of healing. “That’s a separate population than people who just don’t get around to it,” he said.

Going Natural

Joan, a Santa Barbara teacher who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said her oldest child was the perfect baby who almost never cried until the day of her pertussis shot more than 20 years ago. “She cried for a full 24 hours [afterward] and had a high fever,” she said. “It freaked me out.”

Though it’s rare, vaccines can cause fevers that trigger febrile seizures that usually last one or two minutes. They do not cause any permanent neurological damage, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). But the emotional impact they have on parents can influence their decision on whether or not to vaccinate their children.

The day before Joan planned to vaccinate her younger daughter, she met a woman who believed vaccinations had put her 4-year-old child into a vegetative state. “It was my motherly mama bear intuitions,” she said of her decision not to vaccinate her second child. “You can’t explain that to somebody.”

Last year, a study found pro-vaccine messaging to be ineffective; facts, science, and emotions did nothing to make anti-vaxxers change their minds. One message explained the lack of evidence between vaccinations and autism. Another showed information about the dangers of preventable diseases. A third message displayed images of a child suffering from one of those diseases. None of them increased parental intent to vaccinate.

“It feels like you are trying to talk someone out of a religion,” said Dr. Laurel Mehler. “It’s a challenge. It’s a frustration for us who understand vaccinations better than the lay public.

“I can tell someone until I’m blue in the face, there’s no way you can get the flu [from the vaccine],” Mehler went on, adding that part of the problem is that the flu shot is given during the cold season and people often use the term “flu” to mean any kind of cold. “[True] influenza is a really horrible, knock-you-on-your-rear-end kind of illness,” she explained.

The flu vaccine was scrutinized this year because it is not a great match against the influenza A strain that has so far caused most infections. But Dr. David Fisk, infectious disease director at Sansum Clinic, continues to encourage people to get it because it lessens the severity of symptoms.

Joan said she probably would have succumbed to peer pressure and decided to vaccinate her kids today. “It’s a witch hunt,” she said, adding that only her family knows about her decision. She still isn’t comfortable with vaccinations and argued many more shots are required today than they were in the past. Before age 18, children are recommended to receive 14 vaccinations.

Voices against vaccines have recently quieted, said Washington parent and former Parent Teacher Organization president Simon Dixon, though he doesn’t believe those parents have changed their beliefs. A number of people skeptical of vaccinations declined to be interviewed for this story.

The longstanding narrative linking autism and vaccinations also lives on, though the infamous 1998 research paper linking the two has been debunked several times. It doesn’t help that no exact cause of autism is known and that the number of cases has increased significantly since 2000. In 2002, 2.6 percent of Santa Barbara’s special-education students were autistic. That figure nearly tripled to 6.6 percent in 2010.

Legislating Choice?

Exemption rates have started to stabilize and decrease partly because a new law makes the opt-out process more difficult. Beginning last January 1, doctors had to endorse a parent’s exemption form for it to be valid. Exemption rates dropped 20 percent throughout the state, though rate data for individual schools is not yet available.

Last week, Senator Richard Pan — who authored the aforementioned law — introduced a bill that would nearly abolish the personal belief exemption forms. Narrow exemptions for religious or medical reasons would still be permitted. Still in its very early stages, the bill will likely see backlash on both sides of the aisle from people against strict government regulation.

Showing support for the measure, Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson called vaccinations victims of their own success. Measles and pertussis outbreaks, she said, are a significant public health issue. Assemblymember Das Williams said it is too early to weigh in on the bill, though he called for an increase in the number of children who are vaccinated. “That being said, it would be nice to convince enough people to vaccinate without eliminating personal exemption,” he said.

“Unfortunately it takes an event like measles to increase awareness [of low vaccination rates],” said Wada, who has personally never seen measles outside of a textbook. In fact, Representative Lois Capps recently drafted a letter signed by 21 members of Congress that urged the CDC to take additional steps to educate health care providers on the symptoms of measles.

In March, Wada will convene a task force to look at exemption rates at individual schools. He’s searching for the undecided voters of the health world — those not completely against the vaccinations. “Those are the ones we are trying to target,” he said.