Female Farmworkers Unite

Lideres Campesinas Creates Santa Barbara Chapter

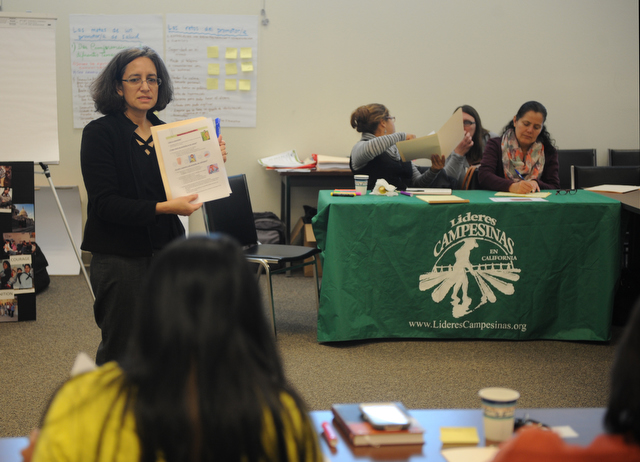

In a small room in Santa Maria, a group of farmworkers and advocates have been gathering Wednesday nights to discuss everything from health and safety in the field to abuse at home. The multipurpose room is nondescript and operates as a space to talk freely about common struggles. But the mood is not down or defeated; a sense of empowerment is alive.

Líderes Campesinas is a statewide organization that formed a chapter in Santa Maria six months ago. They got a serious financial boost last fall from the Fund for Santa Barbara, which is known for its progressive undercurrent and doles out grants to groups determined to get at the root of countywide challenges — social, economic, environmental, and political. Líderes Campesinas seeks to tackle all four.

In 1988, female farmworkers began meeting in Coachella Valley to talk about their mutual difficulties. Initially, their purpose was to unite female workers across California to push for statewide political change — better working conditions and fewer pesticides, among other causes — though it also provided a forum for women to discuss topics rarely spoken about. “In our community, we hardly talk about sexual abuse,” said Suguet Lopez, executive director of Líderes Campesinas. “[It’s] less likely for the women to stand up… so we like to start with the women in this way so they know there are other women out there.”

Lately, addressing pesticides has been on the top of their list. Last month, state regulators unleashed stricter rules for the use of chloropicrin, a fumigant applied on a variety of crops, including strawberries, raspberries, almonds, tomatoes, peppers, and melons. The new rules say notifications for businesses near chloropicrin use must be written in Spanish, the size of buffer zones must be increased, and notice of intent to spray must be made 48 hours in advance rather than 24. In Santa Maria, advanced tarps used to control fumigant emissions in soil have become more popular, and so rules about applying pesticides are less complicated for the growers who chose to use them.

A few Lideres Campesinas members have highlighted that many area schools are located close to crop fields. A statewide report released last year by the California Public Health Department found that Santa Barbara County was among the top 15 counties in the state to use pesticides near schools most often; 45 percent of schools in the county had some pesticide use within a quarter-mile of their campuses. About 12 percent of schools were near fields where upwards of 319 pounds of pesticides were applied in 2010. More than four million pounds of “active ingredients” were applied that year, making the county 12th in the state for most pesticides applied.

At a training session last month in collaboration with Washington, D.C.-based Farmworker Justice, several participants said farmworkers are often not aware which pesticides are being used. Part of the training is to get field hands up to speed about the different types. “[Lideres Campesinas] is extremely effective at reaching farmworker women and delivering information that is credible,” said Virginia Ruiz, director of occupational and environmental health at Farmworker Justice. “There’s a lot of hesitation to speak out against injustices for fear of losing their jobs, or worse, being separating from their families.”

A few members also mentioned that state regulators notify growers when they are coming to inspect their fields, giving them an opportunity to clean the grounds.

This Wednesday, the group will attend the Santa Barbara County Farm Bureau’s first pesticide awareness event at the Santa Maria Fair Park for growers and employees.

Among the Líderes Campesinas participants is Andrea Cabrera, who immigrated to Santa Maria when she was 19 years old after spending most of her childhood in Ensenada. She spent all of her 20s working in strawberry, pepper, and squash fields in Santa Maria and Los Alamos; working conditions varied considerably. Some farms would go more than two weeks without cleaning the bathrooms. The weather was hot. The pesticides were wet. “A lot of people [do not speak up] because they need the work,” she said, adding fears about deportation also add to concern.

Now 34 years old, Cabrera no longer works in the fields. She married a man named Roger several years ago and now studies English at Allan Hancock College. Before that, she completed grade school courses she never got a chance to finish as a child. When I sat down with Cabrera last month during a lunch break in the training, her English had already improved immensely. She said she decided to join the chapter to tell her story to the people working in the places she spent most of her life.

Another member, Olga Santos, 28, began working in the fields with her parents when she was about six years old during summer breaks from school. Her parents were accustomed to dirty bathrooms, no water or shade, and exposure to pesticides, she said. One day, pesticides were sprayed while she was eating lunch with her parents. An outspoken kid, Santos was very upset. “My parents just looked at me and put their heads down,” she said. “They were fearful of losing their jobs if they spoke up.”

“Can you imagine looking at your child and not being able to do anything?” she asked. She went on to explain that a lot of workers do not know their rights, which is why the work of Líderes Campesinas is so important. Now the mother of two girls, Santos can relate to a parent’s perspective and she often thinks about the kids of those who work in the fields.

Also part of the statewide organization is boardmember Elizabeth Cordero, who said since smartphones were invented, some male farmers and supervisors have contests to see who can get the best picture of the women when they are bent over. Cordero emphasized the trainings as essential to help mitigate sexual harassment.

Moving forward, Lopez said there will be four roundtable forums in North County to continue discussing sexual abuse and harassment. In the last month, the group has been engaged in one-on-one work with the community, reaching 150 people.