Colm Tóibín Reimagines the Virgin Mary

Author to Appear at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art

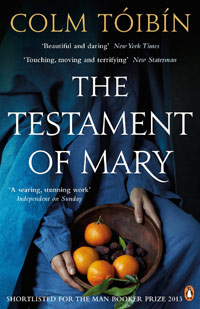

One unexpected benefit of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s Botticelli, Titian, and Beyond show featuring rooms full of major Italian paintings is the associated lecture on Thursday, March 12, by Colm Tóibín, Ireland’s foremost living writer of fiction. What’s the connection? Tóibín has written that his novella The Testament of Mary, which was shortlisted for the 2013 Man Booker Prize, was inspired by a Titian painting, the great “Assumption of the Virgin” that hangs over the altar at the Basilica Frari in Venice. Unlike Titian’s “Virgin,” Tóibín’s Mary remains on the ground and views the miracles and subsequent legends that have grown up around her son as frightening and distasteful. Rooted in the painstaking and sympathetic research that informed his earlier nonfiction book The Sign of the Cross: Travels in Catholic Europe, Tóibín’s Testament journeys into the narrative gaps in canonical accounts of Mary to conjure a voice that could have been hers.

I spoke with Tóibín by telephone from his snowbound apartment on Morningside Heights in New York City, where he lives part time and serves as Irene and Sidney B. Silverman professor of humanities at Columbia University.

In your literary criticism, you’ve dismissed “likeability” as a valid criteria for discussing fictional characters. Since this is an issue that has come up in relation to your version of Mary, could you restate your position on that? Yes, I think particularly if you’re teaching [literature], you really have to set parameters or limits where we don’t care whether you like a character or not …. Often a character has certain qualities because they fulfill the requirements of a pattern [in the larger fiction] rather than in order to provide you with the luxury of being able to judge them as though you know them.

You portray Mary as quite hostile to the disciples who insist on her son’s status as the Son of God. Why does Mary feel that way? What is it about this new religion that bothers her? Well, they [the disciples] needed a story, but they also particularly didn’t want her in the hands of anybody else, and so she became a sort of commodity for them. I mean she even had to cook and clean for them, and she found them less than kind. That moved quickly with her brittle tone into a complete dislike for them and finally got to the point where they irritated her both day and night so that she developed this particular way of describing them. All I was doing really was imagining it and trying to stay as close as I could to what I thought would be her voice.

Was your portrayal of Mary’s hostility to the disciples’ project intended as a reflection on the development of Christianity or on the relationship between Protestantism and Catholicism, for example? I had to keep those kinds of large questions at bay. I think that when you are writing a novel, you have to be quite careful about that. Novelists tend not to be philosophers, because you can always see the other side of everything. You’re actually quite stupid sometimes, as when someone is explaining something that they really believe in, but you’re watching them rather than listening to the belief. Therefore, with her I was watching her eyes and watching her mouth, and I had a sense of her way of moving, this sort of darting about, and that was what I followed to create her.

4·1·1

Colm Tóibín will be at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art on Thursday, March 12, at 3 p.m. For more information, visit sbma.net.