Stuck on the Sucker List

Charity Scams and Other Bad Behavior

SCAMS GALORE: I have a friend whose mailbox is regularly stuffed with solicitations from scads of charities, some legitimate but many or most dubious or outright fraudulent.

My friend is a generous, warmhearted person of modest means whose donations seem to have put him on practically every sucker list that exists.

The letters, generated by a cynical industry of telemarketers, tell heartbreaking stories of the need to help cure or assist people with cancer or feed needy children in third-world countries. In reality, telemarketers pocket up to 85 percent of the donations, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Much of what remains is grabbed by those who shamelessly enrich themselves by running questionable charities with high salaries. Some donations trickle down to the needy.

Case in point: The Federal Trade Commission recently accused a Tennessee man and his family of fraud and using much of the $187 million it raked in, supposedly for cancer patients, to instead buy themselves cars and gym memberships, take luxury cruise vacations, pay college tuition for the kids, and employ family members at six-figure salaries.

They set up sham breast cancer “charities” that sounded legitimate. They operated as “personal fiefdoms,” but little of the donations ever made it to the cancer patients, and now the money’s gone, the FTC said.

Feds have been notoriously lax in cracking down on people like James T. Reynolds Jr., his ex-wife, and son, objects of the FTC action. Critics asked why it took years to shut them down and whether criminal charges will follow. One reason cited to explain the delays is that the feds are overwhelmed: Charities are proliferating like crazy. Everyone wants to get into the money act. There are over one million registered public charities, and mounting.

And they’re easier than ever to start, according to the highly respected nonprofit Charity Navigator (charitynavigator.org), which serves as a watchdog and a place to check out a charity.

You pick a cause, form a tax-exempt organization, fill out a three-page online IRS registration form (1023-EZ), hire a telemarketer, and you’re in business. Let the dough roll in. Many of the so-called charities are nothing more than get-rich-quick gimmicks, paying salaries of $200,000 or more.

One charity claiming to help poor youth in Central America, but based in the U.S., pays its top staff around a total of $450,000 a year. Charity Navigator rates it only one star out of a possible five. Critics question why it sends out sob stories for badly needed donations when it already owns $35 million in assets.

Sure, you can ask telemarketers how much of your donation would go to the charity, but don’t expect an answer, thanks to the good old U.S Supreme Court. In 1988, telemarketers challenged a state law requiring them to tell people they were calling how much of the money actually would go to the cause. The companies called this — are you ready? — censorship.

The court, always on the side of free enterprise, agreed with the companies, according to the Washington Post.

My advice: Give only to charities you’re sure of, better yet ones in Santa Barbara.

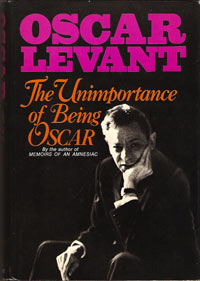

GO TO HELL: There should be a special place in hell for people who mark in library books. Paging through The Unimportance of Being Oscar, the amusing memoir by actor-concert pianist Oscar Levant, I found page after page of comments.

Someone apparently read with pencil in hand, underlining, correcting, or adding details as they went. And on page 158, Mr. Pencil outlined nine whole paragraphs for no good reason except maybe to annoy fellow readers.

When Levant mentioned the erudite editor Clifton Fadiman, another reader helpfully wrote in pen in the margin “lives in Santa Barbara.” Well, he did many years ago, thank you. Fadiman died in Florida in 1999, at age 95.

Levant’s book is full of showbiz gossip. He found Judy Garland quite a head case. “At parties, Judy would sing all night, endlessly; nothing could stop her; but when it came time to appear on a movie set she just wouldn’t show up,” apparently due to stage fright. She sought psychiatric help.

Her analyst advised producer Arthur Freed not to have Judy and director-husband Vincente Minnelli work together, Levant wrote.

“Vincente, who had directed two of Judy’s pictures, Meet Me in St. Louis and The Clock, was preparing her next one, Easter Parade. He was taken off the picture and replaced by Chuck Walters. Because of the analyst’s advice, Vincente didn’t work for two and a half years.”