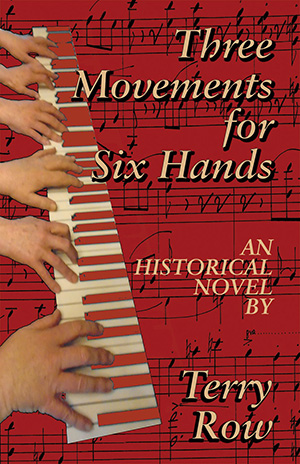

Los Alamos Writer Pens Three Movements for Six Hands

Terry Row Imagines Love Affair Between Composer Brahms and Clara Schumann

It’s probably safe to say that most of us feel we have a novel inside us just waiting to be written. It’s simply that we don’t have the time. Or when we do, there’s always something else that needs doing, like sharpening pencils or rearranging the furniture. Meanwhile, Los Alamos author Terry Row actually does write those novels, his latest being Three Movements for Six Hands, which chronicles an imagined love affair between composer Johannes Brahms and his real-life friend Clara Schumann.

When Row isn’t writing, he’s photographing solar eclipses like the one he shot from the deck of a ship in the Black Sea in 1999. Or he’s managing the porcelain pottery business of his wife, Ramona. Or playing chess online. Or gardening, traveling, or tossing off a bit of poetry in the odd moment.

Row started out in a somewhat more conventional manner. Having shown serious talent as an oboist, he studied at the Juilliard School of Music and then CalArts. There followed a 10-year career playing oboe professionally with such illustrious organizations as the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. He also performed as acting principal oboe with the Santa Barbara Symphony under conductor Frank Collura during the 1979-80 season. However, feeling the financial pinch of devoting oneself to the arts, Row switched gears and went to computer school and for 18 years had a career as a computer consultant and programmer.

Row has authored four books so far, and ideas for more are stewing in his brain. In a recent telephone interview, Row, who refers to himself as an avocationist — one who independently studies numerous fields — talked about writing, photography, and his musical background.

You were an accomplished musician in your adult life. Were you interested in music as a child? ? I started in music at age 6, with piano and voice. My parents realized my musical talent early on, and they were good enough to help me develop that. I didn’t start oboe until I was 8, but I was proficient at it and played in honor orchestras in Southern California.

Are you one of those people who has a tune running through his head all the time? Yes, I am! I wake up in the morning and say to my wife, “The music for today is…” Sometimes I can’t identify the tunes. I once wrote down a tune on paper, took a picture of it, sent it to a pianist friend asking him what it was. He recognized it, fortunately; it’s frustrating to hear a piece of music in your head and not know quite what it is.

I had an experience about 10 years ago. I left the house to do an errand, and had the car radio on tuned to the Beethoven Violin Concerto [Op. 61]. It was very familiar to me; I’d played the oboe part in orchestras. So I got to my destination, went inside, with the music still running through my head. I came out, and when I turned on the radio again, my imagined concerto was absolutely spot-on with the radio. I had kept the same tempo, the same key, in my head all that time.

I think that’s a pretty rare ability. After your 10-year career playing oboe professionally, you switched gears and went to computer school — going from music to computers seems like a drastic change. ? I got interested in computers through a friend who had one when programs were loaded from cassettes. It turned out I was pretty good at it, so in about 1979 I bought an early Apple PC, long before they were popular, and I decided to go to school and become a computer programmer. But musicians and computers programmers are not really so different — they both take information in, in one symbol system, change it, process it, synthesize it, then output something different. When you read music, you read the lines, the notes, and then do what is necessary to create the aural experience. What changes the input to the specific output for both music and computers is your brain. A lot of musicians play with computers as a hobby, and lots of computer people play music or at least love music.

When the flurry of business from Y2K ceased, you left the field of computer data analysis and began another new career, this time as a writer. ? Right. A lot of consulting firms lost a lot of business after 2000, because before that everyone wanted to fix the so-called Y2K problem; there wasn’t so much business afterwards. Interestingly, there was a debate about when the century actually rolled over: Was it the year 2000 or the year 2001? Of course, there was no year “zero,” so it’s 2001. I found an article from 100 years ago that said, in essence: “Who are these fools that think the [19th] century ends with 1900?” Yet a 100 years later, the same debate was still going on. I remember being at a chamber-music party in 1999, when someone said, “Just think — this is the last string quartet playing in the 20th century.” Except for all the ones that would be played for another year!

When the computer consulting jobs faded away, I decided to write about my experiences changing from music to computers. That’s when I wrote Summer Capricorn, which I published in 2006. What it’s really about is the interim jobs I had while I was getting through computer school — tending goats at an organic garden center, working as a psychiatric aid at a mental hospital. It was very different from what I’d done before.

Did you enjoy the computer years? I did, a lot. The pendulum had always been on the creative side, then suddenly I was on the analytical side, and it was a refreshing experience to me. Then when I took up writing, I combined both sides — analytical and creative. And I don’t just write, I also publish; my books are self-published. Clifton Edwin Publishing (CEP) is named after my two grandfathers. Clifton was a words guy, in newspaper publishing, and Edwin was a photographer.

How do you come by your curiosity about so many subjects? I get my vast interests from my dad. He was working for my mother’s father Edwin’s photo studio when Pearl Harbor was attacked during World War II. He felt strongly about defending our country when that happened. He’d always been fascinated with flight, and so enlisted in the Air Force. The stories of missions he flew in the Phyllis Marie, the airplane he named after my mother, and their love story became the inspiration for my third book, Phyllis Marie. Aside from my father’s career in aeronautical engineering, he was an amateur gemologist and raised bonsai trees as a hobby. He was fascinated with mathematics and studied for years and years on a famous Euclidean problem. My mother — who’s 96 and lives in Santa Barbara — provided lots of the oral history that went into that book, as well.

What are some of your other interests? Well, I have another iron in the fire — I run the retail sales for my wife’s pottery shop. She makes porcelain dinnerware, and we have a store in Los Alamos. I run that so that Ramona [née Clayton] has the freedom to do the creative part. We have a new website (terramonary.com), but I did hire a webmaster for that. I can do the website maintenance. The name Terramonary is an anagram of “Terry” and “Ramona.”

What is the book-writing process like for you? ? I take my time finding a new project, but once I decide, I’m a fairly disciplined writer, researching the topic for several months, producing backstories, time lines, and ultimately an outline. When I start to actually write the book, I write five, six, or seven days a week, writing one or two chapters a day. I follow Hemingway’s advice by reading and correcting yesterday’s output each day before starting to write new material. When the first draft is done, I put it away for a while, a month or two, and then I read it, correct it, edit it, and then I send it to my editor. When it comes back, I read it without making changes and put it away again, for another month or two, and then I get down to the business of creating the final draft. During those down times, I work on other projects related to the pottery business like marketing campaigns, or something else unrelated, sometimes a poem, or story, or whatever.

I enjoy research. My first book was semi-autobiographical, so of course there wasn’t really any research. My second book, though, Untarnished Reputation, required a lot of research. I got the idea from a photo I saw in a bar in Idaho. Some of the people allegedly were Wyatt Earp, Virgil Earp, Butch Cassidy … and Theodore Roosevelt, all at a hotel. The thing is, there’s no provenance for that photo, although it’s famous among the Old West fans. It’s called “The Hunter’s Hot Springs” photo. That town no longer exists. The picture really does seem to have been taken on that porch, so I wrote a tall tale of the Old West and how that photo came to be taken.

That book is about Theodore Roosevelt when he assumes the presidency after McKinley’s assassination, and how he deals with the possible scandal a photo of him being chummy with criminals would create. Right. I did a lot of research for that one and made it as historically plausible as possible. With Three Movements for Six Hands, I started with a premise that was not part of the historical record, which is that the friendship between Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann was strictly platonic. But there were a couple of interesting things — first off, Schumann apparently had a stroke about 11 months before their last child, Felix, was born. So I said that he was in very poor health, and perhaps it was Brahms — whose deep friendship with the Schumanns, and especially Clara, is well known — who was Felix’s father. That’s the idea I went with for this book of historical fiction.

Do you end up with a large library of references when you research your books? I used to have a large library, but not anymore. I had a book collection of 600-plus books. They lined the walls of my office. But when my wife and I decided to convert the office — which is a converted gas station from 1920 — into a pottery store, I decided to put the books to good use and gave the collection to the Susan G. Komen for the Cure. I mostly use the Internet now and occasionally buy used books.

I understand you write poetry, as well. Is there a poet you’ve been especially influenced by? I haven’t written enough poetry to publish a book, but I do enjoy writing poetry. Edgar Allan Poe is my favorite — I’ve read everything he ever wrote. It’s so fascinating, especially “The Raven.”

Tell me about your interest in photography. ? I do a lot of astrophotography, things like solar and lunar eclipses, constellations, using time-lapse photography. I’ve done two solar eclipses, in the Caribbean in 1996 and in 1999, a really fine photo taken from a cruise ship in the Black Sea. The whole deck of the boat was filled with cameras and tripods, and I thought that the boat would be moving too much when they turned off the stabilizers. But the eclipse was so slow that it didn’t matter. We’re planning to go to Kentucky for the total solar eclipse in 2017; it’ll be visible from Seattle to Georgia.

What about bird watching? I’ve always enjoyed bird watching, but I’m not very scientific about it. I keep a list of birds seen where I live. We have a fountain in the yard, so I hooked up an outdoor camera, strapped that to a board, and pointed it at the fountain — this was before the drought — and got a lot of interesting birds. There were red-tailed and red-shouldered hawks and a lot of little birds who came to drink and bathe. One particular red-shouldered hawk stayed for an hour and a half. I got within 10 feet of it, hiding behind a big chair, and it didn’t seem to disturb him at all. He just sat and rested, drank, looked around. He didn’t wash, like other birds, but he drank occasionally, and then he flew away.

For more information about Terry Row’s novels, see amazon.com/Terry-Row/e/B002BMFO60/ref=ntt_athr_dp_pel_pop_1.