The Business of Staging Work in Santa Barbara

Our Artistic Community on the Role of the Theater

In the fall of 1994, Rodney Gustafson received a tip about a vacant building tucked away on the southern end of downtown Santa Barbara, a gray expanse of dusty concrete units where State Street and Highway 101 collide. Gustafson had just moved into town, a former dancer with American Ballet Theatre who remembered the city’s bucolic appeal when the company breezed through during a national tour. “I always had my sights set on Santa Barbara,” he recalled, “and knew I’d start my own company and studio and make it work here.”

The space in question was a less than ideal location for any business, let alone one that would usher in a particularly traditional tights and bun-head set; this was classical dance, after all, a genre weighted in sometimes stifling expectation. But Gustafson is a man with an unconventional vision and a self-described “tenacity that drove people nuts sometimes”; this particular set of bricks and mortar was as good a launch pad as any to begin his longtime dream of establishing a studio on the central coast. “A lot of people tried to dissuade me,” he explained, “saying it was a closed-off town and that people were territorial here. But I’d traveled all over the country and knew that competition existed everywhere. I wasn’t going to listen to anyone.”

That spring, Gustafson rallied a group of seven dancers and rented Center Stage Theater’s 130-seat house for the debut of his first evening-length program. Two years later, he’d established a formal company that began touring throughout the States. And 10 years after that, he was selling upward of 1,000 tickets to his season openers, collaborating with the Santa Barbara Symphony and the Santa Barbara Choral Society for the presentations of opulent classical and contemporary dance theater.

To date, Gustafson’s remarkable journey from modest black-box beginnings to Santa Barbara’s first and only performance company in residence at the Granada Theatre has been unmatched by any other area outfit. From contemporary dance to musical theater, our performing arts companies have generationally struggled to achieve a similar balance of creative fulfillment and professional recognition, with space and finances directly influencing their accomplishments.

The Country Club Conundrum

Among the towering palm trees and red-bricked walkways of downtown Santa Barbara stand no fewer than a staggering seven performing arts venues, each one unique in dimension and design, and all within easy walking distance of the city’s main thoroughfare. From the 130-seat familiarity of Center Stage and the similarly sized Alhecama Theatre to the grandeur of the Arlington’s 2,000-seat hall, the physical characterization of each building has traditionally dictated the art being offered inside. “Downtown is tremendously more vibrant now,” said David Asbell, executive director of the Lobero Theatre, “and we’ve got all of these beautiful vessels sprouting up all over the city. The big question all of us need to ask ourselves now is, what are we going to pull into them?”

Programmers are habitually faced with the delicate task of balancing commercial and innovative stage work that might appeal to a broad continuum of audiences. But in a saturated market where theaters are vying for the attention (and purse strings) of a modest pool of 90,000-plus patrons, catering to a niche target audience might be the only difference between thriving and surviving. “Do all of these new venues affect [the Lobero]? Oh, yes, and it certainly puts more pressure on us to pay the bills. But the good news is that it also forces us to be really good at what we were designed for,” said Asbell.

The traditional role of art house as civic soundboard, where programming and demographics once reflected the themes and creative ideals of a diverse community of voices, has shifted dramatically over the last few decades, with theater administrators now working ferociously behind the scenes with influential boards and foundations, determining how best to retain a healthy stock of their proverbial bread-and-butter crowd. They’ve also begun hiring developmental directors with heavy-handed fundraising pedigrees in hopes of wrangling in Santa Barbara’s top-tier donors, an invaluable component that helps ensure a respectable bottom line at fiscal year’s end.

In a 2014 lecture, Diane Ragsdale, former theater and dance strategist for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in New York City — a researcher on the role of theaters within our U.S. communities — posed a glaring question: “Do theaters want to be country clubs? Or do they want to be civil institutions?” It was the shot heard ’round the theater world, with everyone from historians to producers weighing in on the ramifications of an industry sliding dangerously away from its virtuous roots. Lyn Gardner, theater writer for the Guardian, had this to say in response: “If it’s the latter, that means that instead of seeing their own survival as paramount, they must understand the role they can play as enablers and collaborators working with the whole community. If a theatre’s mission has become selling more tickets, more growth, empire-building or simple self-preservation, then that is a theatre that has lost the plot.”

Asbell was quick to agree. “Are art houses supporting art like they did in the 1950s? Hell no. No, a lot of things have changed. But I’m hopeful that the pendulum that has swung too far one way can swing back to a more quality-of-life approach. And that approach has nothing to do with money.”

The Inspirational Factor

According to the latest U.S. Census data for the city of Santa Barbara, 12.8 percent of residents cite some form of the arts as their main profession, making it the third-largest industry after education and professional/scientific fields. Dig a little deeper, and you’ll find that an average of 80 percent of Santa Barbara arts and culture audience members are actual residents themselves, making it pointedly clear that the arts are being sustained and supported by the very community members who live and work within our city limits. Christopher Pilafian, artistic director of Santa Barbara Dance Theater, sees this growing interest as a noteworthy cultural tipping point. “Ideas are currently afoot here, people are making and sharing work, people are encouraging critical thinking of that work, and people are attending performances with a greater understanding of what the artistic process implies,” he said.

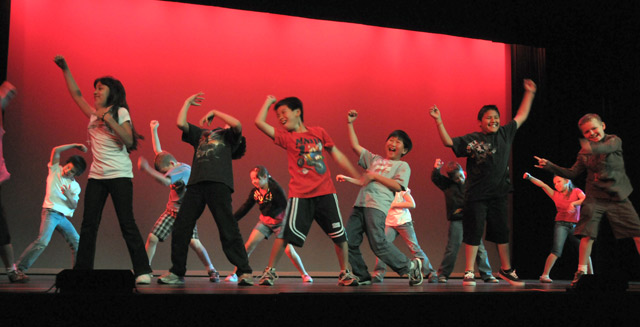

Programmers such as Celesta Billeci of UCSB Arts & Lectures recognize the significant correlation between artists and audience, curating a powerhouse season of lectures and performances around a primary mission statement of enriching and engaging our community. “For us, the educational outreach component of our programming isn’t an afterthought; its right up there with securing a big name like Alvin Ailey or Yo-Yo Ma,” Billeci stressed. From master classes to student assemblies to workshops for at-risk youth, Billeci credits the business of the arts for its empowering ability to change the course of people’s lives no matter what their age. “The moment I stepped into a theater to see my first performance, I was hooked,” remembered Gustafson. “I went to see the Joffrey Ballet, and the magic of that performance will always stay with me.” Devyn Duex, director of Nebula Dance Lab, agreed: “There is something magical about the theater experience, and [it] is the trigger for artists to awaken their paths towards performance.”

Dianne Vapnek of DANCEworks curates her programming with similar awareness: “I like to bring in a fresh and different perspective from a group of dancers you may never get to see otherwise. A little East Coast flavor always motivates the soul.” With open rehearsals and intimate dance salons, Vapnek’s approach encourages an invaluable dialogue over the myriad ways art can be developed and experienced. “The contributions of the curators in our community such as Celesta Billeci and Dianne Vapnek have helped to raise awareness among the casual dance lover, and has helped them to become a more sophisticated and engaged audience,” said Pilafian.

Awareness and interest have a way of rushing through the city with the ferocity of the Santa Ana winds; nurture a community, and they will return the favor by building audiences through their infectious passion and creative development. “We have an arts community here that is unparalleled, and I really feel that local companies bring the interest in, and set the stage for visiting companies,” added Gustafson.

Location, Location, Location

For a Santa Barbara performance company, selecting the right venue to stage new work presents a sobering set of determining factors, with the constraints of a prudent budget conventionally steering the decision along. “The Granada is the closest to the kind of stage I spent my career on,” said Pilafian. “It’s a wonderful theater, and I would be thrilled to provide that experience to my dancers. But the seats! The seats are so many! We just don’t have that size of an audience draw yet.”

Cutting one’s teeth in a more intimate venue has traditionally allowed for greater artistic risk, an unparalleled connection to the audience, and the invaluable ability to produce multiday programs. How to prioritize these influences varies from company to company. “We really like the intimacy of Center Stage for the style of theater we do. It’s really valuable to be able to connect with our audience eye to eye and see their reactions immediately. Also, it’s the most affordable theater to rent in Santa Barbara,” said Samantha Eve, director of Out of the Box Theatre Company. Area choreographer Weslie Ching agreed: “Aside from Center Stage, most current theaters are out of my budget; it’s still very expensive, and I’m doing it pretty bare-bones.”

Some area theaters, including Center Stage and the Marjorie Luke Theatre, have implemented a formal rent-subsidy program to assist artists during the critical leap toward the big stage, an invaluable tool that every company director interviewed for this story mentioned utilizing at some point in their careers. “Last year, we gave away $18,000 to 32 different Santa Barbara–based groups, so it’s a feather in our cap knowing we can directly impact our local community,” said Rick Villa, manager of the Marjorie Luke Theatre, whose tireless community-advocacy work has allowed more companies to make the intimidating jump from a black-box environment to an 800-seat proscenium theater.

“Each house brings in such a diverse audience,” noted Duex, “and as a growing artist, it takes us being seen by different audiences, which comes from being in different places. But being in different places can’t happen without some coordinated effort by the theaters themselves. Making space available for emerging companies is critical because it’s so much harder if you’re not one of the big guys. It’s a matter of opportunity.”

“Frankly, I’m just tired of convincing people to see the value in helping out the underdog,” said Kyra Lehman, creative director of Proximity Theatre Company. As such, the search for affordable space has forced her off the conventional route, and onto more creative venues. “We’ve tried everything from dance studios to school auditoriums to barns and backyards,” she explained. Her company has currently partnered up with the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara to present a series of site-specific works that utilize both MCA’s downtown digs and its satellite gallery housed inside of the Hotel Indigo. These alternative performance venues have grown in popularity as the glaring reality of rising rental fees elbow many emerging companies off the traditional stage. “I believe in this work so much, and we work so hard,” said Lehman.

Recognizing the challenges that an emerging artist faces, venues like the newly renovated Alhecama Theatre offer a streamlined, frills-free rate that allows a company the freedom to tailor each production according to scope and budget. The Lobero Theatre applies modest subsidies to programming that specifically impacts area youth. Even the theaters once seemingly indifferent to the needs of a small start-up seem to be catching on to the inherent value of nurturing the arts from the ground up. “We want to do it right, so it’s a slow process, but we’re fully committed,” stressed Carrie Ohly-Cusack, a Granada Theatre boardmember specifically tasked with researching the current needs of our arts community. Granada Executive Director Craig Springer confirmed that the organization is currently looking to hire a full-time community outreach coordinator by summer’s end, a critical step in the fieldwork needed to take an accurate temperature of a wide-ranging audience.

Nurture vs. Nature

A visit to the administrative offices of some of Santa Barbara’s leading theaters and one is immediately struck by their tangible personalities — eerily accurate reflections of their reputation among the community. The Marjorie Luke, a cozy, open plan of smiling young faces behind a streamlined trio of desks; the Lobero’s gregarious director motioning spiritedly over a charmingly disheveled workspace; the Granada’s labyrinthine suites perched regally above State Street in the Arts & Culture Center.

Their role within our city’s intricate network of resources is much more than a passive vessel for entertainment or a placeholder for our cultural musings. For an artist, the incomparable weight of relevancy is second only to the simple gratification of sharing personal stories with others. “My belief is that critical mass and tipping points are parts of the energy trajectory of any community, and we’re in a very interesting time for that gathering around this particular field,” mused Pilafian. “In a healthy civic environment, artists are inspired and dedicated to their process, and motivated to share the results of their process as manifestations of their own personal artistic growth.”

Ching drove the point home: “All of those big-billed dance companies that come through our town had to start somewhere, and somewhere along the way, a community saw value in their work. You can’t go from the Center Stage to the Granada without nurturing in between. That’s all Santa Barbara artists are asking for.”