Archie McLaren’s Indulgent Life

Central Coast Wine Classic Founder Reflects on Black Panthers, Avila Beach Pollution, and the Munchies

Archie McLaren, the Santa Barbara–residing bon vivant responsible for creating and sustaining the Central Coast Wine Classic for the past three decades, may never have stumbled into fine wine if it weren’t for smoking weed — specifically by pretending to puff on his first joint, which was rolled by a burly Black Panther in Memphis during the heat of the civil rights movement almost 50 years ago.

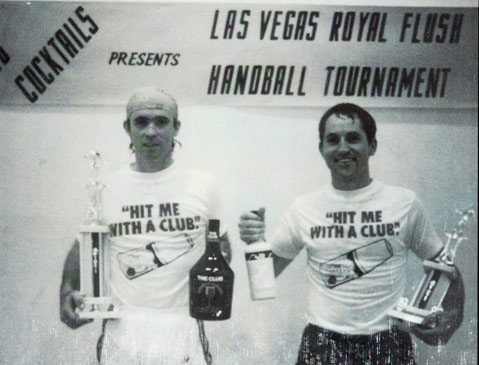

McLaren was hanging at the house of his good friend Russell Sugarmon, a Harvard Law–educated African American who founded the first interracial law firm in Memphis and had made paparazzi-like headlines for marrying a white German woman. An athlete his whole young life — high school tennis champ of Tennessee who won a scholarship to Vanderbilt, traveling handball wizard, etc. — McLaren never smoked, so he tried the do-not-inhale trick probably around the same time as a young Bill Clinton.

It didn’t work. Minutes later, McLaren was mesmerized by the amazing smells wafting out of the kitchen, where Sugarmon’s wife was whipping up one of her fancy feasts. “I’d never had anything more exciting than a cheese dog, but [the weed] exploded my ability to experience aroma and flavor,” recalled McLaren recently. “I had a transcendent case of the munchies that night. It changed my entire life.”

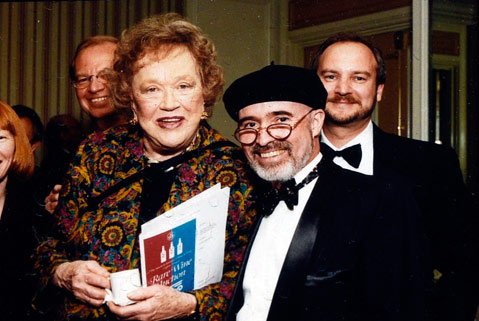

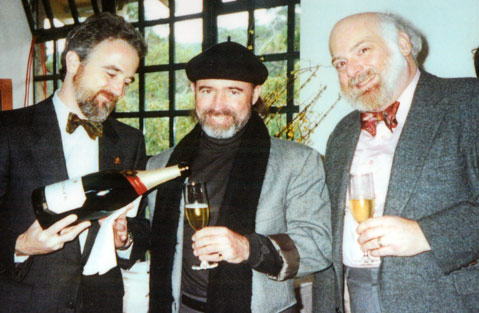

What a life it’s been. Inside McLaren’s second-floor pad above the corner of Chapala and Gutierrez streets, the walls and shelves are overloaded with athletic trophies, commendations from the world’s most prestigious orders of food and wine, posters of personal heroes like B.B. King, Elvis Presley, and John Lennon, and mementos of his proudest accomplishments. That includes not only events that he started and/or ran, such as the Central Coast Wine Classic, the World of Pinot Noir, the International Festival of Méthode Champenoise, and the San Luis Obispo Mozart Festival, but also his roles in a much more dire affair: his decade-long, tooth-and-nail fight against Big Oil, which had disastrously polluted his former hometown of Avila Beach. And most impressively to modern foodies, the high-ceilinged condo is littered with photographs of Archie mugging alongside the past century’s top gourmands, from chefs such as Paul Prudhomme, Emeril Lagasse, and Jacques Pépin to his good friends like wine critic Harvey Steiman and culinary superstar Julia Child, with whom he dined regularly.

Scattered amid it all — and yes, despite his dapper dress, he’s the first to admit his flat is a giant mess, which is one reason he’s never married — are the plans for this year’s Central Coast Wine Classic, which raises about a quarter-million dollars each year for regional nonprofits. After a hiatus last year, during which time McLaren suffered a minor stroke, the 2016 edition will be the 31st Classic. But it’s the first time the series of tastings, meals, and auctions will spread from San Luis Obispo County into the heart of Santa Barbara, where events will occur at the Santa Barbara Inn, S.B. Wine Collective, Courthouse Mural Room, Santa Barbara Club, and Pat Nesbitt’s Summerland estate, among other locations.

That’s because, after more than 40 years in S.L.O. County — and after considering a move to Lyon, France, the ancestral home to haute cuisine — McLaren moved to Santa Barbara about 18 months ago. He immediately found the community both welcoming and exciting, particularly from a food and wine perspective. “It’s vibrant here; it’s exhilarating,” said McLaren. “Within a four-block radius, there are cuisines of over a dozen cultures. You can’t do that in New York; you can’t do that in Chicago; you can’t do that in Seattle; you sure can’t do that in Lyon. I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else in the world.”

Balls to Barrels

Archie McLaren was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1942. “I moved to Memphis the next day because the music was better,” he joked. “I was right.” He excelled in school and sports thanks to multitasking and extreme focus. “I started playing tennis in the 8th grade and was state champion in the 9th,” he explained.

After riding a tennis scholarship to Vanderbilt and graduating in 1964, he taught at segregated schools in Mississippi, where he was asked to join the African-American faculty’s basketball team, which he enthusiastically accepted. When he arrived for the first game, he was the only Caucasian in the gym. “I have never felt so graciously accepted,” said McLaren, but others weren’t so happy. “I was run out of Mississippi by the Ku Klux Klan.”

He wound up back in Memphis, teaching and coaching tennis during the day at Memphis University School, pursuing a law degree at the University of Memphis at night. That’s about the time of the transcendent joint, which fired up an interest in food that led him to America’s culinary capital. “I’d get a bag of weed and a date and go to New Orleans,” said McLaren, who soon met celebrity chef Prudhomme and, later, chefs like Susan Spicer, Lagasse, Wolfgang Puck, and Pépin.

But he was still drinking crappy wine, specifically cold duck, primarily to get the weed burn out of his throat. “I can’t believe what I’m seeing,” his musician-friend David Porter, the songwriter of “Soul Man,” told him in 1972. “You’re drinking shit. I’m gonna bring you something you need to be drinking.” Then came a bottle of Asti Spumante, which opened his eyes to better beverages, followed by the one that grabbed hold of his soul: a 1971 Bernkasteler Doctor Riesling Auslese from Germany. “It blew me away,” recalls McLaren. “The texture was beyond description.”

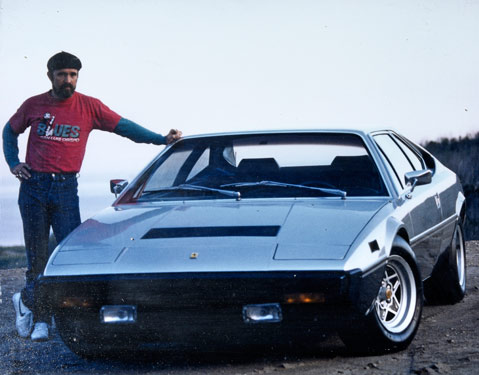

In 1974, McLaren put his law degree to work by taking over marketing in California and Nevada for West Publishing, the largest legal publisher in the world. That required a move west, so he “played the map like a Ouija board” until his finger landed on Morro Bay. He drove out in a Ferrari Daytona with his friend Peanuts, a nightclub owner in Memphis with a Morro Bay connection, and quickly dove into the Central Coast’s nascent wine country.

McLaren’s job at West Publishing, where he’d work until 1990, expanded to include the entire Orient, so he was spreading access to legal archives and their enlightening jurisprudence during heady, espionage-soaked times in Beijing, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Manila. But by 1977, Morro Bay grew too sleepy for his tastes, so he moved to Avila Beach, then an end-of-the-road party town full of bikers, hippies, and everything in between. “There was no supervision of any kind,” said McLaren, who’d open his growing wine cellar during the soirées, often to his morning-after chagrin.

In 1984, the San Luis Obispo public radio station KCBX asked McLaren if he’d want to start a weekly program about wine, and he obliged, kicking off a more-than-two-decade-long run for The Wine Drinker’s Guide to Indulgence. “The demographic audience for fine wine was growing,” said McLaren. “I interviewed all these winemakers who’d never been interviewed before, because in 1985, nobody understood the subject; nobody understood how good the wines of the Central Coast were.” As such, many credit McLaren as the first in the world to loudly bang the drum of quality winemaking from Santa Barbara to Paso Robles, long before the mainstream wine media recognized the region.

The next year, KCBX and McLaren started the Central Coast Wine Classic as an annual fundraiser for the station. The 1985 edition was not successful — “It sucked,” said McLaren, who covered losses with his own money — but it quickly grew into the top regional wine event. Among other highlights, McLaren convinced the curators at Hearst Castle to allow for a small dinner on the grounds of the state park in 1989. Thirty people came that first year, but it grew to more than 200 by 1994. The dinner, which has showcased multiple celebrity chefs, including Lagasse, Gary Danko, Pépin, Spicer, and more, is considered one of the top annual culinary tickets on the planet, which is why it costs $1,250. This year’s, featuring chefs Christophe Eme, Laurent Quenioux, James Sly, Michael Hutchings, and James Siao, is on August 11.

The KCBX format remained until 2004, when, after a couple of slower post-9/11 years, the station focused fundraising efforts on just the Live Oak Music Festival. That gave McLaren about six months to incorporate a new foundation and run the event on his own, which means writing the occasional personal check to cover costs. Since then, he’s raised $2.5 million for 125 different nonprofits working in the studio, performing, and healing arts. He even manages to kick KCBX some money, as well.

Fighting Oil, Enjoying Life

In 1989, more than a decade after McLaren moved to Avila Beach, a neighbor uncovered a toxic lake of underground oil beneath his basement, and the community quickly learned that the uphill Unocal tank farm had leaked untold amounts of petroleum into town. As president of the Avila Beach Water District, McLaren became a thorn in Unocal’s side, getting publicity in national newspapers and threatening to take it global. When Unocal finally relented and agreed to a massive excavation and remediation plan, McLaren became chair of the Avila Beach Front Street Enhancement Committee, in charge of rebuilding the town. The process took more than a decade. “I had a knot in my stomach for 10 years,” said McLaren. “Your psyche is torn apart when your town is.”

But when Avila Beach “reopened” in 2001, McLaren felt that its soul was gone. He painted his house a rainbow of colors to bring back cheer, and then enlisted Carpinteria’s Eddie Tuduri of The Rhythmic Arts Project to organize Avila Drum Day in 2004, when 50 percussionists of all stripes banged their instruments from 11 a.m.-midnight. “We tried to rebalance the energy of the town,” said McLaren. It worked, sort of — real estate values skyrocketed, forcing out many longtime residents and causing Avila to become dominated by vacation rentals and tourists rather than locals.

That’s partly what prompted his move south to Santa Barbara, where he’s found a more comfortable environment, both in culture and politics. “It’s very conservative in San Luis Obispo County, and I was just a shade to the right of Che Guevara,” said McLaren. “I was anathema to a lot of people there. Here, you get both sides, but up there, there’s only one.”

In August 2015, McLaren suffered a minor stroke, which slowed his short stature down a tad. He hasn’t smoked weed in years and barely drinks, since two glasses get him mighty buzzed. But he’s busy as ever, hosting a television program on KEYT every Sunday night at 5 p.m. and putting together the final touches on the 31st Classic.

“I’m jumping off a diving board,” said McLaren of spreading the event into Santa Barbara, which has tripled expenses. “I have no idea if it will be successful, but honestly, I don’t give a shit. In the worst of all worlds, I’m throwing a party. In the best, it’s very successful.”

No matter what happens, this year’s beneficiaries — the Boys & Girls Club (healing arts), the Hearst Castle Preservation Foundation (studio arts), and the Léni Fé Bland Foundation (performing arts) — will receive everything raised by the classic’s Fund-A-Need Auction Lots, as those don’t play into the bottom line. “If it fails,” he said, “I pay for it.”

He’s already decided that there will not be a Central Coast Wine Classic in 2017 — “I need to heal,” said McLaren — and that may mean that 2016 is the last. There’s no succession plan, nor would it work without him.

“Archie has a very magnetic power that brings in a certain breed of people, and [the Classic] is a lot like a family reunion,” said his friend Yuri Gevorgian, the Los Angeles–based Armenian artist known simply as Yuroz. “There’s an atmosphere being established by the leader. He is the event.”

The Central Coast Wine Classic runs August 10-14 at various locations. See centralcoastwineclassic.org for specifics and tickets.