New Santa Barbara School Superintendent Listens

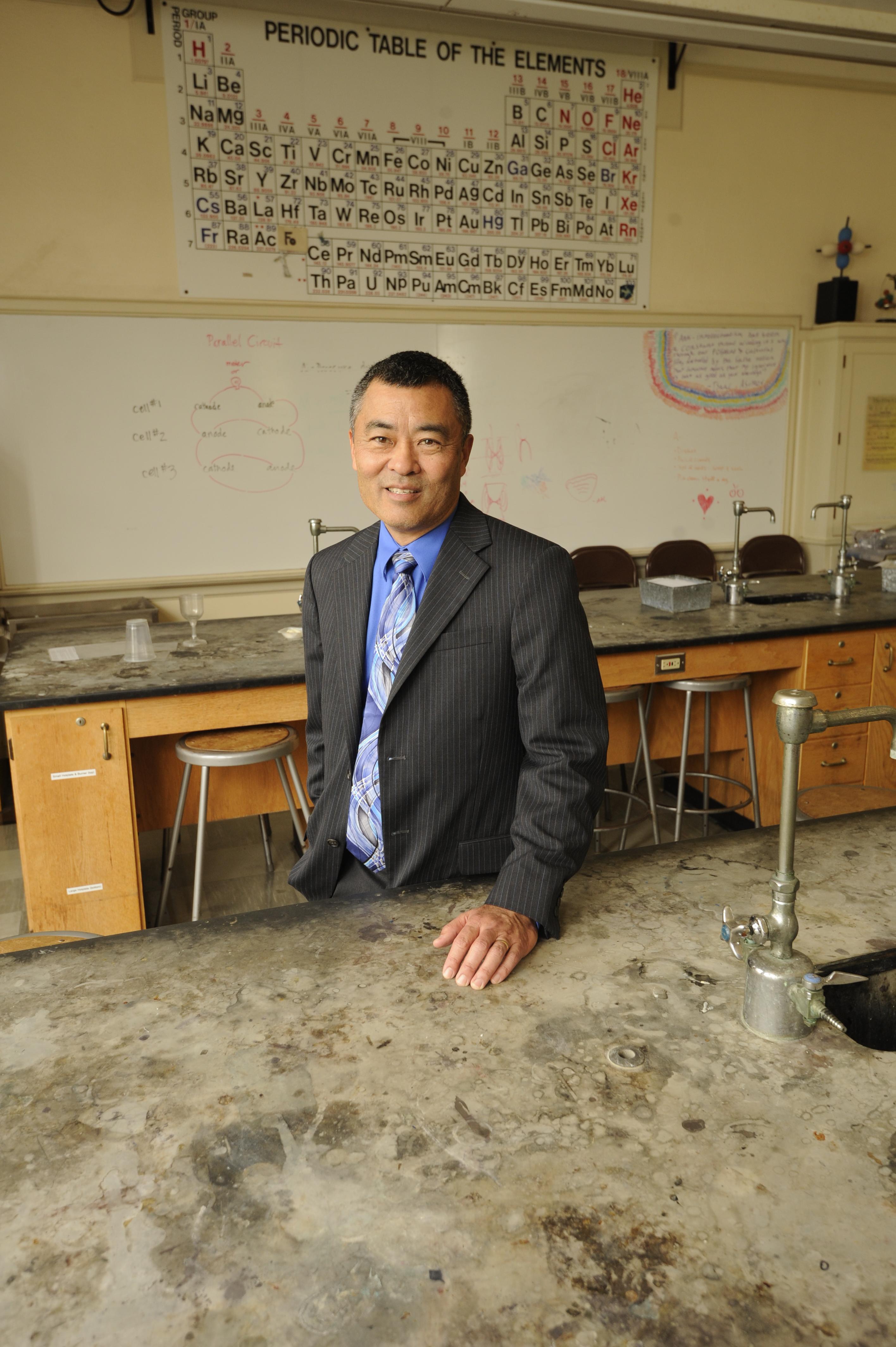

Superintendent Cary Matsuoka Leads by Listening

Soon after coming aboard last summer to lead Santa Barbara County’s biggest K-12 school district, Superintendent Cary Matsuoka (pictured) launched his listening tour, a 90-day endeavor to take the temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure across 13 elementary schools, four junior highs, and five high schools. He still has not spent enough time in the individual schools and with the faculties, but let’s be realistic, Matsuoka said: With 800 teachers and 15,185 students — 9,029 of whom are Latino, 3,569 categorized as English learners, 1,933 in special education, and 24 in foster homes — “you’re never done listening.”

Matsuoka’s temperament, described as thoughtful and approachable, differs starkly with that of his predecessor, Dr. David Cash, who once described himself as “a bull in a china shop kind of guy.” Before he retired, Cash developed a lot of necessary programs — including the Strategic Plan, Facilities Master Plan and funding, and strides in cultural sensitivity. Part of Matsuoka’s job has been to maintain momentum and layer it with his own experienced vision. That Matsuoka was a teacher for 17 years factored greatly into the board’s decision to hire him.

“He’s a great next superintendent,” said Kate Parker, the president of the five-member Board of Education. She agrees that Matsuoka is a refreshing change but points out that, most importantly, he has measured leadership, which came in handy last fall when the district asked voters (successfully) for $193 million in bond monies. It is also a helpful temperament when working with four brand-new boardmembers with no previous experience as elected public officials.

Graduating from UC Davis in 1979, Matsuoka’s original plan was to become a senior teaching pastor in a church. He got his credential and started clocking real-world experience. Along the way, he changed his mind about the seminary but stayed in the classroom, first at a private school, then at Saratoga High School, teaching chemistry, computer science, and physics. He said he eventually got bored with teaching, but he couldn’t understand why. “It turns out,” he said, “I’m wired for leadership.” He made the shift to administration in 1997, first as an assisstant principal at Lynbrook High School in San Jose.” In 1999, he earned a master’s degree in educational administration from San Jose State University. In the 10 years before joining Santa Barbara Unified, Matsuoka spent five years as the superintendent of Los Gatos-Saratoga Union High School District and then leading the Milpitas Unified School District.

While Matsuoka’s career was born and raised in the Bay Area, Santa Barbara has been very much part of his life. His wife, Polly, graduated from Dos Pueblos High School, and her father was a chemistry professor at UCSB for 30 years. The Matsuokas got married in Santa Barbara in 1980. Now that it’s been six months since Matsuoka took over the wheelhouse at Santa Barbara Unified, The Santa Barbara Independent sat down with him last week to see how he’s settled in.

When you showed up, what did you notice, and what goals did you set?

It was really clear during the application process that the district staff felt stressed, pulled in many directions. They were doing too many things. That was a concern of the board. So I came in wanting to understand what’s going on, what’s important, and to not add any new major initiatives. My message was three things: First, equity. Second, figuring out how to improve our practices … but without giving any specific direction because most people can figure out what they need to do. And the third was to evaluate our work better. I think in education, we’re great at starting stuff, but we often don’t evaluate [whether it’s] working.

As you started listening, what surprised you about the district?

The demographic profile. I had no idea that Santa Barbara had a Latino population this big. And it has inner-city neighborhood pockets. Not like L.A.’s inner city, but where there are neighborhoods that feel both middle-class and lower-class. We have neighborhoods where low-income families can actually afford to live and be a community. It would be a sad day for Santa Barbara if those families couldn’t live here. I’ve worked in places that are pure high wealth, and it’s pretty, but it’s not healthy.

Who reached out to you early on? And how did listening to those groups help shape your understanding of the community?

Our Latino advocates, several community organizations, and a group of foundation leaders all reached out. The generosity of Santa Barbara is pretty amazing. Here, there is the potential to focus it on one district. This is different than any place I’ve worked. Silicon Valley has a lot of money, a lot of foundations, but their work is spread out over the entire Bay Area — whereas in Santa Barbara, this is it. The potential to partner with these foundations to make positive changes is really, really good.

Equity is very important to you. What does that look like in the classroom?

When I look in our advanced placement classes, do I see the same mix of white students and Latino students as I see out in the community? I do not. That’s a long-term issue to figure out. You can’t just mandate, okay, let’s put more Latino students in AP. It actually starts in K3 [kindergarten through 3rd grade]. For a lot of our immigrants, it starts with learning a language and teaching students how to think, and how to deal with rigorous classrooms. The most important step we can take to close the achievement gap is to support our English-language Learners (EL). Becoming fluent in a second language, both orally and in writing, takes a minimum of six years, and we need to focus on literacy for our EL students.

It must be a challenge to give the best educational opportunities across all the schools, especially at the elementary level, for example.

Our schools have different demographic profiles. Washington and Roosevelt have a different student body than Franklin, Cleveland, and Harding and McKinley. Those last four schools are 98 percent Latino. We have a lot of English-language learners overlaid with poverty, and those are two challenging life circumstances to overcome.

It’s a lot easier for a school like Roosevelt to raise a lot of money than it is for Franklin. It’s a sort of fundraising inequity. Is it fair to think that the playing field ought to be more level? I don’t think you can. The parents who run the Washington and Roosevelt school foundations know how to create a vision, how to fundraise and network. Whereas a Latino family where the parents are working two or three jobs, they don’t have time [nor the] experience to fundraise. It was true in districts in Silicon Valley. You have Palo Alto, Los Gatos, and Saratoga, and they raise millions of dollars. And the Milpitas Foundation would raise $20,000 a year. It’s just a function of the context of social economics.

You have said that using supplemental income can help that situation. How?

The whole LCFF [Local Control Funding Formula] system that Governor Jerry Brown brought in four years ago was a great philosophical policy shift. He said some students need a greater investment to be successful. This formula sends more money to districts around English-language learners, low income, and foster youth. What we need to do as a district is take that philosophical policy framework and use those supplemental dollars at our high-needs schools. My goal is to shift more resources to our high-needs schools [but] not dramatically because we don’t have a ton of money.

What’s the district’s biggest challenge?

Special education has been probably the biggest challenge. We were not fully staffed, so that just creates issues. It’s been a long process for the district. It’s gotten better from what I hear over the last five or six years, but we have a lot of work to do. The special-ed space is overburdened with more kids than they really can carry. And English-language learners are over-identified as needing special ed. That’s going to take some time to solve. Once we get that calmed down, the needs of special-ed students will continue to be deep and complex. But then my team can focus on them.

Is that the first step to address in special education?

No, it’s multiple layers. I don’t have the luxury of focusing on just that problem. We have to work on our moderate to severe classrooms. You know, those are our most vulnerable students, and we need to figure out how to support them.

And I’m starting to pay attention to the dyslexia question. I don’t know much about that field, but from what little I’ve read and the stories I’ve heard … if you do the right interventions [when they’re young,] then they can manage the regular classroom environment.

Let’s talk about the budget: Is it accurate to say the district needs to make about $6 million in cuts in the next couple of years?

Over the next two fiscal years, yes, that’s accurate. We’ve been working on recommendations to the board for next year. It’s a $2.5 million problem. I think some of the bigger strategies include looking for expenditures that aren’t resulting in progress — software platforms that we’re not using, for example. I was told our enrollment [district-wide] was going to decline. We’re going to monitor this carefully, and if it does look like enrollment is dropping, then we can cut some of our staffing costs. That’s our biggest tool.

What about specific schools?

We’re taking a pretty deep look at Open Alternative School because their enrollment is down. But we’re going to keep the school open. I’m actually encouraged with their numbers for next year, but we’re going to monitor their staffing much more carefully. When you run a school of 84 kids, you still need a principal, an office, a custodian. Our biggest elementary, Franklin, is pushing 550 kids.

But you can’t do anything about pension costs.

I cannot because that’s all mandated by California rules. We need to start communicating what those costs are. It’s increasing at such a fast pace for both teachers and classified [employees]. We need to put a dollar number on the growth every year so that everybody understands this is now an annual cost.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of the new board?

The three women [Laura Capps, Wendy Sims-Moten, and Jacqueline Reid] who were sworn in on December 13 are a really good group. They’re in it for the right reasons. My initial experience is they’re going to stay enrolled as boardmembers and not get into the details, which is really important for me as superintendent. They’re all committed to equity. I’ve only had a couple of board meetings with them, and they ask questions but they don’t overdo it. Sometimes boardmembers will get on a soapbox and talk for five minutes before they get to their questions. They’re not doing that. They’re fun. They have a sense of humor. The other new member, Ismael Ulloa, I just barely got to know, but I like his life experience. He’s a product of our district, he’s bilingual, he had to overcome a lot, and he’s really committed to helping our Latino students get to college. This has all the marks of, I think, a great school board. But it takes a while to learn the role. Honestly, it takes a full year of going through the entire board calendar before you go, “Oh, I’ve seen that before; it’s not new.”

What can the district do to attract and retain good teachers?

We have got to provide more support, coaching, and mentoring, especially for our first- and second-year teachers and our special-education teachers. I really need to focus on the younger staff because I think we hire people, and then we lose them for a variety of reasons. The cost of living [in Santa Barbara] is an issue. I’ve already seen evidence of that. I’ve lost some people mid-year, and it’s because they’re commuting from Santa Maria or Lompoc or Ventura.

What is the very latest on the armory building?

My goal is to be in escrow by summer. There was an underground shooting range [in the basement], so there’s a lot of lead in the wall and the ground. We’ve got to figure out the cost of cleaning that up. Another hurdle is negotiating with the state about the price. That’s actually the big driver. We need our own appraisal, but we’ve heard that the state isn’t interested in our appraisal. That’s what happens when you deal with the state agencies. But it is such a great piece of property.

What are the best uses for it?

It’s situated right between two of our secondary schools. The large structure, the gym, we’ll be able to use for athletics for both schools, and it’ll be a great after-school resource. And we could really use another outdoor field. The garage buildings have really tall ceilings, and I think we could turn them into career-technical spaces or artistic spaces. I’d want to have a conversation with SBCC about a partnership where we teach high school courses by day, and they could teach community college courses after school. When we get some movement on the purchasing, I want to hold conversations with the whole community about what they think of this space.

What about the Trump effect? How did the schools react to the election?

We did some proactive planning around inauguration day. We just wanted to get some messages out to stay on campus and take your finals; do not leave campus to go protest. I also did not want them mixing with the adult protests. It was pouring rain that day, which was really good because I think it just kept everybody indoors.

How do you anticipate Trump’s stated immigration policies will affect Santa Barbara schools?

We don’t track undocumented students, and I don’t anticipate that the immigration policies will target schools. I hope not. I mean, we would do all that we could to protect our undocumented students and their families. But another concern is how it is going to affect our enrollment. Are we going to lose families out of fear? Are they going to say, ‘I don’t want to live with this uncertainty. I’m going to go back to Mexico?’ If your school starts shrinking, you might have to think about closing a school. Closing a school is no fun.

Will this impact what is happening in the classrooms?

I think we’ve got to work with our high school students to help them believe that democracy is still a good idea. I think right now it’s hard for people to believe that America is a democratic nation because … Trump is not behaving like a leader of a democratic country. He’s behaving almost like he’s king. His first 10 days have been horrible. Look at the way he’s making decisions. If I led that way, I’d be fired. If I was just creating mandates, then firing off emails saying we’re going to do this without consulting with my board, my principals, with legal — it’s just crazy. It’s going to be a real test of the checks and balances that our founding fathers put in place, which are some of the strongest checks and balances of any design of a nation. It’s going to be a real test of how we move forward.

You’ve said a personal goal was to help the professionals around you grow. Did you have a mentor?

Over my career, I’ve had different people who’ve mentored me both inside and outside of education. And that’s really valuable. We can’t see ourselves, we can’t see our weaknesses, and we also can’t see what’s coming. So I’ve had superintendents, experienced ones, with whom I’ve spent time and listened and learned. For the last five, six, seven years, my goal has been to mentor a cohort of principals and superintendents. Here, I have a cabinet of seven people … so I’m just helping them grow, to get better at their jobs. In that group, there’s going to be future superintendents.

Has your spiritual life played a role in your development as a leader?

My biggest growth personally has been having a set of spiritual directors in my life just to stay grounded, to stay balanced. This job is crazy. It’s just such a hard job. It’s stressful. You could lose yourself. You could lose your soul in this kind of job. You could just be so immersed in the work or so worried about what people think about you or worried about your job security.

How are you and your family adjusting to Santa Barbara? What do you like to do for fun?

Our sons are all adults, great guys. Two live in Brooklyn, and one is in San Jose. My wife and I live near Hope Avenue. We landed in a beautiful spot. We wake up and look at the mountains. We bought a pair of stand-up paddle boards about four years ago, and they have not been in the water in Santa Barbara since July. So my wife and I are saying, “Okay, we’ve got to get in the water by March.” We’ve paddled out of the harbor. Santa Barbara’s stunning.