Patrick Comiskey’s Ode to Syrah (and Roussanne and…)

Q&A with Author of ‘American Rhône: How Maverick Winemakers Changed the Way Americans Drink’

The story of syrah in America is about as tumultuous as it gets for a piece of fruit. It starts quietly, with sporadic, interspersed plantings prior to Prohibition, then rises on the counter culture waves of the 1960s, before crescendoing in popular appeal by the 1990s, thanks to a handful of iconoclastic winemakers. Then suddenly, largely because too many syrah vineyards then exist, its star fades by the mid-2000s. And just when its bell is almost totally rung, syrah is rising like a phoenix once again today, riding both the ripe richness of Paso Robles and the more savory styles of Santa Barbara, Washington State, and elsewhere.

Wine writer Patrick Comiskey tracks all of this — as well as the fates of other Rhône varieties like roussanne, viognier, and grenache — in his new book American Rhône: How Maverick Winemakers Changed the Way Americans Drink. Told in a narrative form based largely on exhaustive historical research and colorful characters, like Bob Lindquist of Qupe, Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon, and Manfred Krankl of Sine Qua Non, American Rhône is now the bible for this movement, not to mention the most engaging wine book I’ve read in years. But maybe that’s because, like Comiskey, I can’t get enough syrah, especially when done strangely.

I spoke to the Los Angeles-based writer a couple months ago, and what follows is an edited version of our chat.

What was it about syrah that set you on this path? It was an epiphany I had with one of Sean Thackrey’s early vintages of Orion, which is a really strange wine. It’s this sort of wine that is definitely savory, but it insists on being tasted on its own terms. It’s so outside the realm of what’s usual even for syrah that you have to take notice. I just stood up and said, “Not only is this a great wine. This is a weird wine.” That encapsulates what I love about syrah. In some way or another, its greatness lies in its weirdness. Not every great syrah is weird, but the greatest syrahs have a little bit of weirdness to them.

When did you realize that you had a book-length project on your hands? The book took an embarrassingly long time to write. I signed my contract at the end of 2007, and then I spent three years researching it and realized there was all of this 19th century material that neither myself nor my publisher bargained for. The topic just really needed to delve into the history, and that required a bit more time, and it changed the nature of the book, too.

We were looking at it like a guidebook, and I was going to tell you who’s a great syrah producer and who’s the father of viognier and that sort of stuff. But I realized that I wasn’t interested in writing a book like that. It was the history that mattered to me. So I was a good two-and-a-half years into the research when I went to my publisher and said, “You know that book? I’m not gonna write it now. I’m gonna write this instead.”

And then the syrah fortunes in the market started to turn, so that became a thing I needed to address as well. It was such a long process that the book’s subject was forced to change in the course of writing it.

What has been the response? Very positive so far. I think that there are some people who really do appreciate that it’s a narrative and not a guidebook. The Rhône Ranger crowd is ecstatic that their story is being told. People didn’t really realize that what they were doing was history-making, which is how I approached it. They became engaged and energized by the fact that someone was trying to historicize their lives.

If I’m proud of anything, it’s the fact that the true pioneers of this category are very pleased with the outcome.

Tom Hill, who is a big Rhône aficionado and has been collecting since the early 1980s, gave me some of the biggest praise. He lived it as an observer more than anyone, and he said that there are things in here that I don’t even know. That’s high praise to me.

Will the popular rise of the red blend category help Rhône blends grow? It certainly takes care of all that syrah production, doesn’t it? That’s really why that’s there, to some extent.

Sometimes they seem like kind of cynical or excuse wines, like, “We didn’t know what to make, so we just made this. We didn’t want to get serious, so we just found a really good marketing hook.” That’s what they really did with The Prisoner, which is a fluke, but a great fluke. It’s tremendously successful.

Blends can also be compelling. I’m all for easy drinking, but I want something that challenges and charms me. If it’s just big and gloopy, I’ll drink that zinfandel.

Where is this the heart of this movement? For better or worse, the epicenter of Rhône varieties is the Central Coast, Paso Robles in particular, with Santa Barbara being a close second. Every category, from the point of view of marketing, needs an epicenter, a place that will anchor the movement. Paso is very interesting place that is making very high quality wine with a modest number of standouts. I want the wines to be more challenging. That doesn’t mean they’re not frequently very satisfying and appealing, so I think they are as good a place as any to represent it.

Santa Barbara is more serious and they’re more intellectually engaged to really explore their terroir. The geography of the transverse valley makes that exploration really dramatic. There are some really interesting players in Santa Barbara that are exploring their intellectual curiosity within the vineyards of Santa Barbara County, and that’s so cool. To watch Sashi Moorman transform himself, to watch Jim Knight transform himself with Jelly Roll, to watch the guys at Holus Bolus — they’re restlessly coming to terms with how they can push their wines and their aesthetics into new and interesting directions.

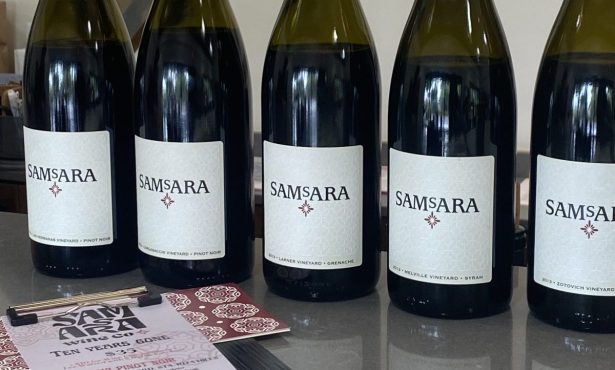

I’m just as jazzed about syrah in the Sta. Rita Hills and Chad Melville’s Samsara project as I am about those wines coming out of the Santa Barbara Highlands. There are dramatic differences between those two types of wines.

Do you think the mainstream will ever turn to syrah? They have to. Syrah’s biggest misstep was to go mass market. That footprint is shrinking. The ambitions in the market are a little more modest. That’s going to allow for there to be a little more funk in the glass. They won’t have to be easy drinking. They can be challenging, the way the better pinot noirs challenge.

Comparisons to pinot are very apt. There’s mass market pinot, but you and I know that it’s hard to gravitate toward that stuff. It’s too insipid.

The same is true of syrah. If you start to really explore the flavor boundaries of syrah, you get into some very interesting places. The same guys who make great pinot are experimenting with syrah and doing similar things, like whole cluster fermentation.

Tell me about your affinity for roussanne. I’m a huge fan. It’s a very intellectual wine and it will never be on everyone’s top shelf, but it is such a spectacular wine in California. California would be the world leader in roussanne if they’re not already. They are very demanding of those who buy them, but that is true of Meursault, that’s true of Côte-Rôtie, that’s true of Barolo. I’m not saying California roussannes are there yet — some of them are — but they could be.

What do the French think of America’s Rhône winemakers? It took them awhile to come around. At the American-French colloquium that happened in the early 1990s, it appeared to be very collegial. But it was organized by Robert Haas [of Tablas Creek], who had the foresight to transcribe the entire proceeding. It was pretty obvious that the French felt superior and, at that early stage, were never going to cede their ground.

Having said that, the place where France and California have come together with the greatest sense of ease was at Hospice du Rhône [annual event 1992-2012; became biennial in 2016]. Not only did that lead to some great relationships and friendships; it forged import companies that were founded on the picnic tables of Paso Robles as well as joint ventures, like Yves Cuilleron and Morgan Clendenen making a “world” viognier from Condrieu and the Central Coast.

There’s a younger generation in France just like there is here, and there is no reason to think that they won’t get closer together. France is just a way slower country to move in terms of wine than the United States.