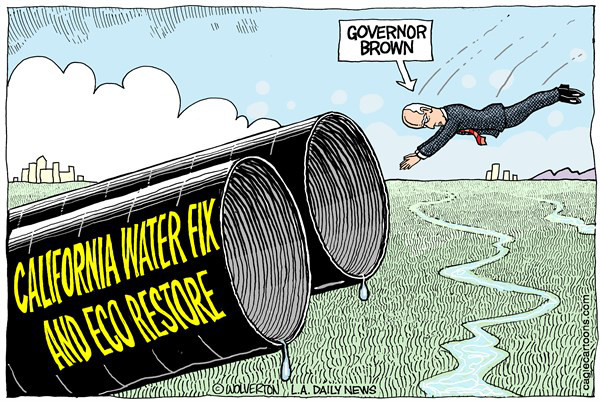

California WaterFix Won’t Fix Anything

Project Likely to Exceed $64 Billion, Provoke Water Ownership Issues

Governor Brown’s proposal to fix California’s water problem by building massive tunnels to shunt Sacramento River water past the Bay/Delta and south to Los Angeles water consumers and San Joaquin Valley farmers isn’t going to fix anything, let alone make our water supply more reliable. The state admits the tunnels will not supply any new water. The proposal is replete with misconceptions and misrepresentations, and it has a false underlying basic premise — that there is enough water in California to meet our needs if only we could bypass the Delta.

Let’s begin with our water supply. The State Water Resources Control Board, the agency responsible for permitting water to be taken from its source and given out for beneficial use, has never done an inventory of how much water is available. Through the years it has passed out water rights to a myriad of people and entities as well as the State Water Project and its contractors without actually knowing how much water is reliably available.

The California Water Impact Network (C-WIN), a nonprofit organization of which I am president, completed a three-and-a-half-year study in 2012 that quantified the water available from the rivers, streams, and mountains of Northern California and compared that amount to water promised for consumptive use downstream. It was found that the water Control Board has promised five and a half times more water to contractors than is sustainably available. The University of California at Davis did a similar study two years later and came to the same conclusion. So to say that the tunnels will make our water supply more reliable cannot be taken as fact. Real solutions will come only when the State Water Resources Control Board, the state agency with the fiduciary responsibility to grant and revoke all water rights permits in California (except Native American water rights which supersede all others), actually quantifies real available water.

Tunnel construction costs are estimated to be $17 billion according to state documents, Since the state admits that design of the project is only 10 percent complete, how this construction figure was derived is an intriguing question. We know from past experience with large infrastructure projects that cost overruns are inevitable. In addition, the cost of construction does not include the interest on the debt or the maintenance costs, all of which will be passed on to the ratepayers who use this water.

C-WIN’s economic analysts estimate the total project cost, with interest, will exceed $64 billion.

Among the important constituents of the tunnels project are the farmers of the San Joaquin Valley. Two large aqueducts bringing water from the north supply much of the irrigation needs of the farms: The State Water Project (SWP) and the federally administered Central Valley Project (CVP). One of the largest irrigation districts benefiting from these aqueducts is the Westlands Water District, a major water contractor of both the Central Valley and State Water projects. Westlands recently voted 7-1 not to participate in the WaterFix tunnel project because the cost was prohibitive. San Joaquin farmers were expected to pay 45 percent of the total cost of the project. In voting no, Tom Birminghan, general manager for Westlands Water District, said, “The decision was not to participate in the California WaterFix due to the cost and uncertainty concerning the water supply that would be created by this project.”

The cost and uncertainty were highlighted in the State Auditor’s Report on WaterFix, which found that the State Department of Water Resources had not completed either an economic or a financial analysis to demonstrate the financial viability of WaterFix. The auditor found this, along with numerous questionable oversight shenanigans, which should give pause to any entity considering signing up for the WaterFix.

Now it appears that the Los Angeles Metropolitan Water District may be willing to fund almost 100 percent of the project thereby assuming that its ratepayers are prepared to bear the cost.

While the Met is flexing its muscles and feels that its ratepayers can afford the price, many smaller districts and counties that participated in the original State Water Project cannot. There is a real threat that this multi-billion-dollar project could bankrupt some districts as they struggle to pay both their own maintenance costs and as well as the bill that would come in every month from the WaterFix.

And then comes the real billion-dollar question: Whose water is it anyway? Ignored in much of the WaterFix conversation is the legal principle of the Public Trust Doctrine. In simple language, the Public Trust Doctrine says that water and our other public trust resources belong to the people, to everyone, and can’t be privatized for profit. It is a principle established in the California Constitution in 1854 and has passed down through the ages beginning with Emperor Justinian (300 AD) through the English Magna Carta to our own U.S. Constitution (1784 AD). The Doctrine is an important piece in solving our water problems. Invoking the Public Trust Doctrine will show how much water we have to share, and who and what have water rights, including the environment. Doing this should be the first order of business before building massive tunnels.

Carolee Krieger is executive director of the California Water Impact Network.