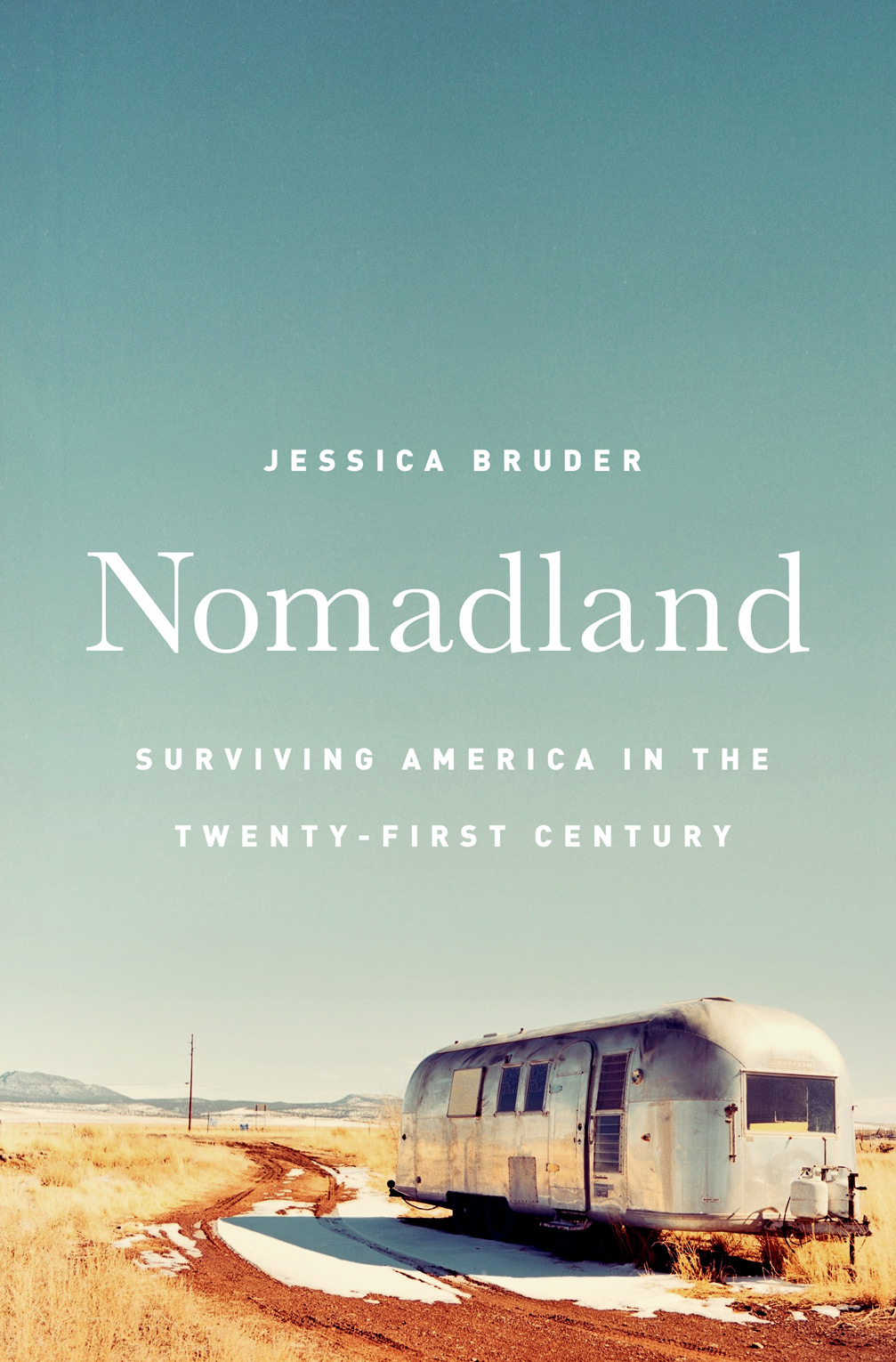

Reviewed | Jessica Bruder’s ‘Nomadland’

Author Writes About Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century

Local citizens who argued against Santa Barbara’s recent Oversized Vehicle Parking Ordinance will find a strong advocate for travelers, campers, and “vandwellers” in Columbia School of Journalism professor Jessica Bruder. Her new book, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century, is immersed in participant observation and written with the grace and wealth of detail one finds in the work of creative nonfiction giants like Edward Abbey and John McPhee.

The protagonist of Nomadland is Linda May, an intelligent woman in her sixties who has had a run of bad luck and can no longer afford the rent on even a modest mobile home. Her solution is to scrape together enough money to buy a used motor home and later, downsizing, a tiny trailer she calls “The Squeeze Inn.” Linda’s ultimate goal is to build an “earthship” in the desert — “a unique, self-sufficient, and ecologically sound dwelling” made of recycled materials. However, until she can bring that dream to life, she travels around the country from one low-wage job to another, most of them specifically designed to attract poverty-stricken but tenacious seniors who have their own transportable homes.

While following the migrations of Linda, “Swankie Wheels,” Scottie, Chere, and others, Bruder decides to purchase a used van, which, in keeping with the whimsical naming practices of the vandwellers, she calls “Halen.” Halen takes her to the Rubber Tramp Rendezvous in Quartzsite, Arizona; an Amazon distribution center in Haslet, Texas; the Adventureland theme park in Waterloo, Iowa; and a sugar-beet processing factory in northern North Dakota. American Crystal Sugar lures workers with the promise that they will have an “unbeetable experience,” but Bruder, “stressed, sore, and covered in dirt,” soon quits the jobs. Later, when she hears a coworker has broken her wrist, “with a twinge of guilt” she feels “relieved that it hadn’t been me.”

Bruder sympathizes deeply with the people she writes about, who insist they are “houseless” not “homeless,” but she’s also candid about the chief difference between them and her: She can always walk away from the backbreaking work and return to her well-paid job and comfortable apartment; the vandwellers don’t have that option. Initially, Nomadland seems as though it will be an elegy for working- and lower-middle-class seniors battered by the financial crisis and the “jobless recovery,” but the more time Bruder spends with the vandwellers, the more she comes to value the freedom and courage they have achieved through the very difficult choices they’ve been forced to make.