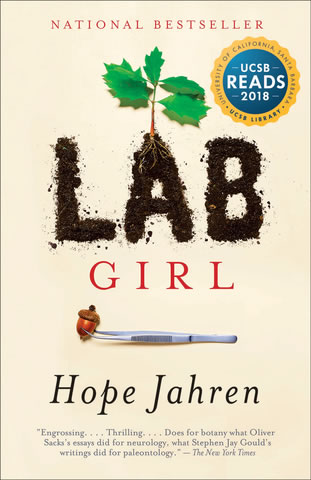

UCSB Reads Presents ‘Lab Girl’ Author

Hope Jahren Will Read from Her Best-Selling Book on April 3

It’s not often that an award-winning scientist writes a massive best seller, but that’s exactly what geobiologist Hope Jahren has done with Lab Girl, her unforgettable memoir of life in the trenches of modern laboratory research. Brought up in the lab of her dad, a professor at a small college in rural Minnesota, Jahren has risen through the ranks from her beginnings as a PhD candidate at Berkeley to posts at Georgia Tech, the ‘University of Hawai‘i, and now the University of Oslo, where she continues her work using stable isotopes to study fossil forests dating to the Eocene. Her marvelous, enchanting book weaves together her experiences as a hardworking yet sensitive young woman battling through the tradition-bound protocols of hard science with stunning, imaginative descriptions of plant life in all its wondrous variety.

Lab Girl is this year’s UCSB Reads book, which means that hundreds of free copies were distributed to students at Davidson Library in January, and multiple events have been held since to encourage people from every part of the campus and the community to discuss their impressions of Jahren and the book. The project reaches its climax on Tuesday, April 3, when Jahren arrives at Campbell Hall to deliver a lecture and meet her readers. I spoke with her by phone from her office in Oslo last week.

Lab Girl is a hit, and you’ve been traveling in support of the book. What’s the response been like? I get a lot of reader mail; I thought I was the only one who writes to authors! You have to write a book for its own sake, and you have to let it go once it is done, so what comes first is that it becomes just what I want it to be. But I do love that people stopped to write me. That means that I got the voice right.

In terms of what they said, people see different things in it. As they go through stuff in their lives, a book can be a friend, and in some cases that was what happened. Mostly, though, the responses were varied, because readers found value in different parts. Sometimes people come up to me, and they are full of talk about trees, and then others only want to talk about Bill and what a great character he is. It makes me happy that there’s more than one way for the thing to work. And I know from my own reading that the meaning will change over time. When I reread a good book I often realize something that I hadn’t seen before.

Given all the attention that’s been focused lately on women’s roles in the workplace, and on bringing more girls into science, do you feel that the timing of the Lab Girl’s publication was good? You mean was this “the Lab Girl moment”? Let me tell you something; I’ve been living this moment for years! Seriously, it is hard for me to fully appreciate how timely people feel it is because I’ve been doing this work for so long, and the book is a reflection of decades of being a woman in science. I will say that as I have become more senior in the profession, and in particular after the publication of the book, I’m often asked to make some kind of appeal to girls to become scientists, which is fine. But I also want to encourage boys to be nurses.

It is an important question though, and I do feel I have something to contribute, which is this: an honest account of what this life is like. Who are you going to be around if you work in science? What are the conditions? Let girls judge for themselves whether or not it’s for them. The other question that I get asked all the time is “how do you know when someone has the makings of a scientist?” And that’s a hard one, because there is no one accurate picture. What does tenacity look like? Because that’s what it takes. It can occur in unexpected places. When I see young people in Brooklyn who sacrifice everything to their dream of being filmmakers, hustling locations and fixing equipment as they go, I think they would be good scientists.

What was the writing of the book like? What ideas did you use to keep yourself on track? One thing you will notice is that every chapter has a happy ending. There are disasters and setbacks, but things have a way of coming back together. There’s no problem so big that some combination of love and work can’t fix it. That’s the moral.

As far as the style goes, I challenged myself by pledging that I would not use one word that someone would have to look up in a dictionary. I wanted the book to be entirely written in a language we could share. Another constraint I set was on the length of my descriptions. I was determined not to go on and on. I approached it as though it were a conversation, and I had only one chance to tell someone about a leaf so that they knew how important it was, how important trees are. Not everybody has 20 years to devote to learning these things, but that doesn’t mean they can’t understand them.

Data is like a kaleidoscope for me: I turn it and turn it until I get the image that I want, the one that tells you what I know to be true. I’ve been doing that for years in the classroom. Say it so that it sticks. Make it into a story that’s accurate. I feel like a comedian sometimes because I’m constantly testing my bits to see if they land, if they get the right response.

Part of it is that I love to sit and make these calculations in my head. I’m from Minnesota, and the people I grew up around didn’t talk much, so I learned early that when you do open your mouth it’s good to choose your words carefully.

Are you working on a new book now? What’s it about? Yes; in fact it’s mostly written. It’s about the last 50 years — my time, as I am nearing 50. I’m writing about changes in the natural world over that period, about food use, and about what it means to be alive at this moment in time from a geobiological point of view. It’s an exercise in looking at the data and finding examples that are instructive for how we live now.

Is it an optimistic book? Yes, I think so. There are plenty of things to worry about, but this is our time. There’s so much love in my life. When I look at the good things we can accomplish, I don’t think we have the right to feel otherwise than optimistic. Hope requires courage. We have to believe that we are up to the challenge, and I do believe it. I trust in the combination of love and work. When we have both those things at once, it’s hard to imagine that we won’t prevail.

4·1·1

Scientist Hope Jahren will talk about her book Lab Girl on Tuesday, April 3, 8 p.m., at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. The lecture is free and open to the public. See guides.library.ucsb.edu/ucsbreads2018.