Review | ‘Salt & Silver: Early Photography, 1840–1860’

Santa Barbara Museum of Art Shows Massive Collection of Early Paper Photos

William Henry Fox Talbot was a 19th-century scientist and inventor who created the photographic process known as “salted paper,” in which sodium chloride and silver nitrate are combined to create silver chloride, a light-sensitive solution that can fix images on ordinary paper. Thanks to Talbot’s innovations, a generation of early experimenters was able to print detailed, stable pictures from paper negatives, allowing them to operate free from the cumbersome apparatus associated with rival technologies such as the daguerreotype.

Salt & Silver: Early Photography, 1840–1860, on view at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA) through December 8, presents more than 100 beautifully preserved examples of these salt prints from the Wilson Centre for Photography, a private archive in London. When SBMA Curator of Photography and New Media Charlie Wylie saw that this extensive, once-in-a-lifetime show was coming to the West Coast, he negotiated a Santa Barbara stop on its tour, and the result is a revelation. To see the variety of ways in which these early figures approached the new technology allows 21st-century eyes to shed preconceptions about what photography is and what it has wrought in the world. Touring Salt & Silver, one journeys back in time to a world in which the act of taking a picture was not yet taken for granted.

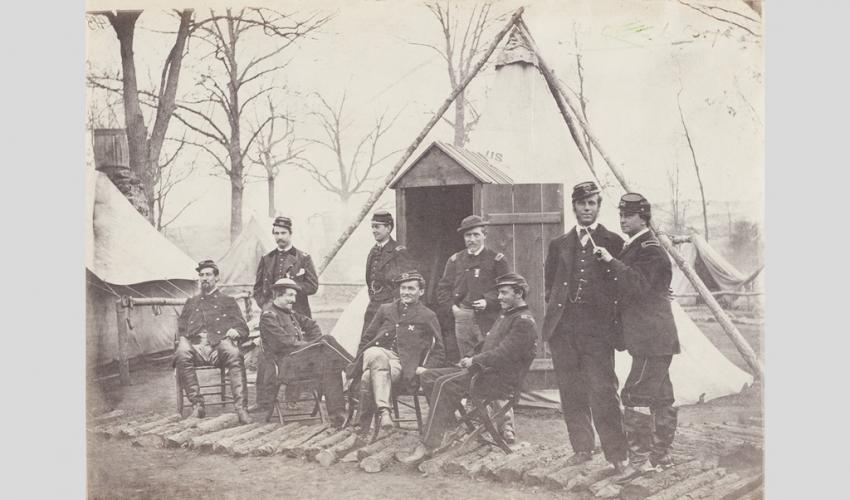

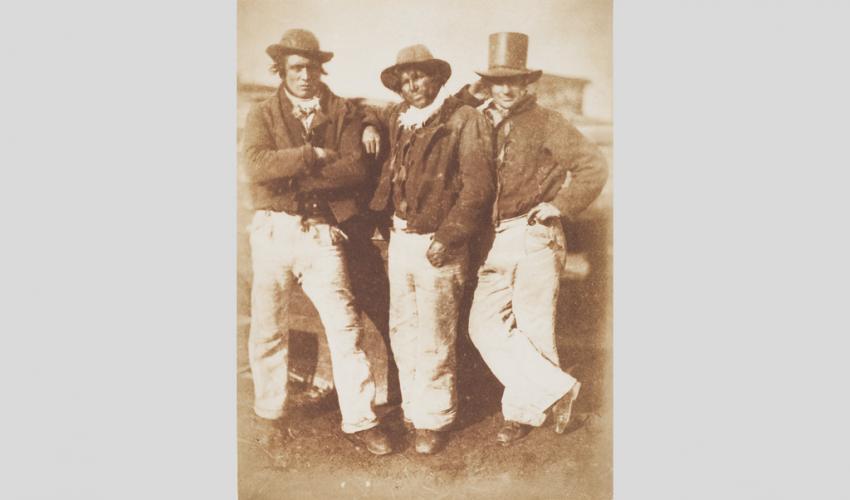

Walking through the exhibit, one witnesses the birth of the modern eye. Talbot’s “Articles of China” (1844) takes inventory of a variety of similar objects in a way that reflects the impulse to order and categorize the world that’s emerging from such nascent disciplines as archaeology. Other images from the same period, such as Talbot’s group portrait of “The Fruit Sellers” and “Newhaven Fishermen (Alexander Rutherford, William Ramsay, and John Liston)” by D.O. Hill and Robert Adamson, deliver the kind of information about humans and the poses they strike in different settings that one would expect to encounter not only in sociology or anthropology but also in fiction and drama.

Some of the exhibition’s most striking pictures document the early stages of the industrial revolution. Edouard Baldus shows the “Entrée de la Gare d’Amiens” as it looked in 1855, a new, brutal hardscape largely devoid of both people and nature. Early photos of historically significant ancient sites such as the Parthenon and the Pyramids of Giza must have shocked their first audiences with their level of detail and the absence of painterly considerations.

Given the long exposures required to make these images, the range of attitudes expressed in the portraits astonishes. Contrapposto, casually crossed legs, and heads cocked and propped on hands abound. It seems there was something about the new medium that demanded spontaneity, even if that quality had to be painstakingly contrived.

As with the category known as early music in the classical music world, this field of early photography has captured the imagination of a new generation of scholars and practitioners. The accompanying catalog, with its pair of roundtable discussion transcripts in lieu of the more traditional scholarly essays, and its sensuous matte paper design, displays a sophisticated sensibility in relation to the material that’s very much of this moment even as it delivers aspects of that time. Don’t miss the opportunity to explore the wide-ranging world of Salt & Silver. It’s an eye-opener for the ages.