Steelhead Legal Battle Expands to Santa Maria

Twitchell Reservoir Releases Just Enough Water to Strand Migrating Fish, Enviros Charge

Los Padres ForestWatch has sued the Department of Interior, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Santa Maria Valley Water Conservation District, charging that Twitchell Reservoir dam operations are inflicting serious ongoing damage to the steelhead trout, a federally endangered species, that rely on the Santa Maria River. The lawsuit, also brought by San Luis Obispo Coastkeeper, charges that the timing of water releases from the dam — designed to maximize groundwater recharge — has effectively rendered certain reaches of the lower river all but impassable during critical times in the steelhead’s spawning cycle. Such flow alterations, the lawsuit alleges, “are harassing, wounding, killing, trapping, capturing and harming steelhead.”

The remedy would require a change in the timing of downstream releases, argued attorney Maggie Hall of the Environmental Defense Center (EDC), who filed the suit with Jason Flanders of the Aqua Terra Aeris Law Group and with Cooper & Lewand-Martin. The amount of water that needs to be released to accommodate the steelhead, Hall said, is relatively modest, only 4 percent the total volume of water stored in the dam on any given year. The Bureau of Reclamation was sued because it owns the dam, which it paid to have built in 1958 and for which it established the protocols outlining exactly how much water can be released downstream and when.

This is the first such legal action involving the steelhead and the Santa Maria River. Typically, such fights have involved the endangered fish in the Santa Ynez River, its many creeks, and the creation and management of Bradbury Dam. Recently, the State Water Resources Control Board finally resolved a longstanding legal dispute dating back no less than 20 years over steelhead in the Santa Ynez River watershed that will affect the timing and quantity of downstream releases necessary to establish a sustainable habitat for a creature biologically accustomed to surviving the South Coast’s intense and sometimes violent oscillations between floods and drought.

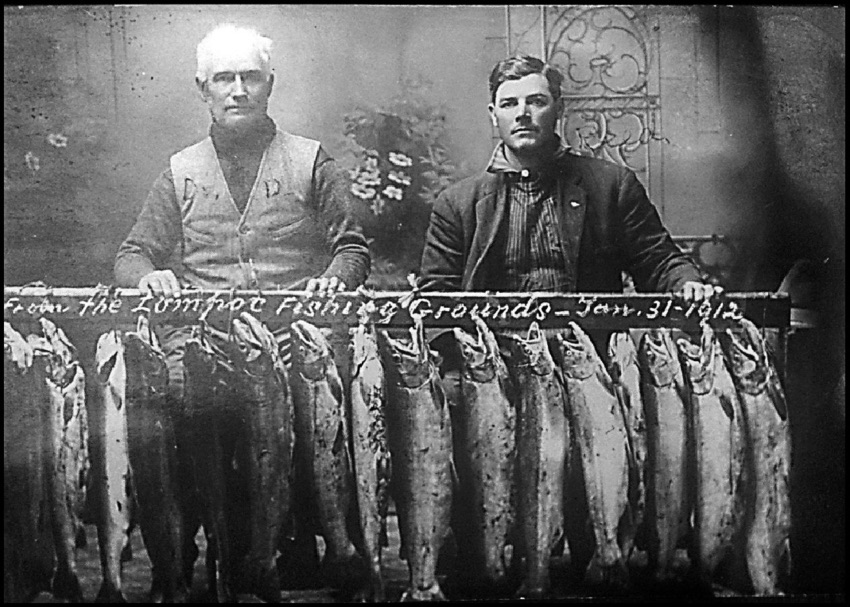

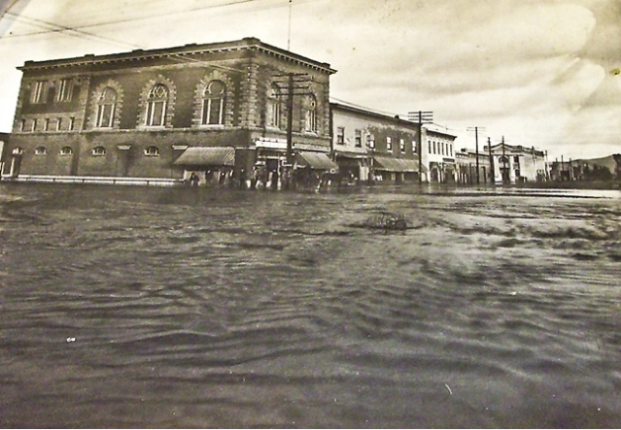

Seventy years ago, according to the lawsuit, the Santa Maria River boasted the second richest run of steelhead in Santa Barbara County. In 1941, when the river was bursting at its banks from heavy rains, city residents were fishing for steelhead from city streets. But since the dam was built, the steelhead population in the river has dwindled dramatically to mere remnant numbers. That’s because the dam was built on the Cuyama River about five miles east of where it joins with the Sisquoc River, at which point it becomes the Santa Maria River, which runs 24 miles before it empties into the ocean.

Steelhead are behaviorally complex creatures. They’re born in river tributaries and go out to sea upon adolescence. When they return — and they always return up the same stream from which they came, guided by the scent of the water— their body mass is significantly larger. Returning females lay three times as many eggs as females who remain landlocked and never make the trip. Landlocked steelhead are genetically identical but are known simply as rainbow trout.

In this case, the Twitchell Reservoir landlocked many upstream steelhead, preventing them from making the life-cycle-defining trip out to sea. It also blocks off much river habitat that would be suitable for spawning and early development. Even so, the lower reaches of the Santa Maria River offer some habitat suitable for steelhead — but only if the dam is releasing enough water to allow the steelhead to make it back upstream.

According to the ForestWatch lawsuit, dam operators have very carefully calibrated the size and timing of downstream releases to maximize infiltration into the aquifers under the river. For the steelhead, that’s problematic in the extreme. These downstream releases, the lawsuit alleges, offer the fish just enough water to get them partway up or down the river, but not all the way. The lawsuit identifies a particular pinch point in the river — Fugler Point about five miles downstream from Santa Maria — where the fish find themselves stranded and die.

Correction: The succession of rivers was fixed on Oct. 21, as Twitchell is on the Cuyama River, which joins the Sisquoc River, not the other way around.

You must be logged in to post a comment.