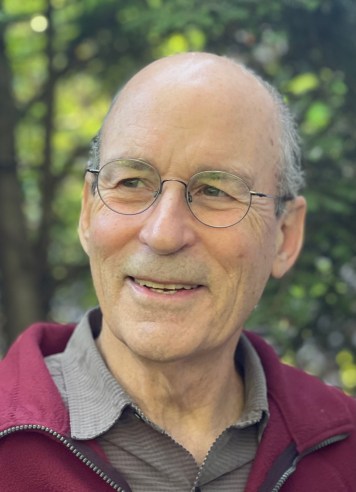

Tracy Kidder Riffs on Doctor Whose Patients Are Rough Sleepers

The Story of Jim O’Connell Who Built Boston’s Flag Ship Medical Program for Homeless

[Update: Tue., Mar. 14, 2023, noon] UCSB Arts & Lectures announced on Tuesday morning that due to the dangerous storm conditions predicted today, this evening’s sold-out event featuring Tracy Kidder in conversation with Pico Iyer will no longer be held in person but will be available via livestream. Ticketholders will receive an email with a link and instructions, or can call the A&L ticket office at (805) 893-3535.

[Original Story] Let’s face it: Saints are boring. By any reckoning, Tracy Kidder just wrote another book — Rough Sleepers — about a modern-day saint. Yet it’s anything but boring. That’s the art of Tracy Kidder, who for the past 45 years has reigned as one of America’s genuine masters of deep-dive nonfiction. His work has been called “literary journalism.” You can see why. Describing a homeless man on his way down — and a pivotal character in Rough Sleepers — Kidder wrote, “Now he smelled of hangover, of a good time turned sour, moist, overripe.”

This man, whom Kidder called Tony Columbo, was charismatic, charming, and tragically gallant. And a rough sleeper, a turn of phrase that Kidder borrowed from 19th-century England. Kidder uses it to describe people who prefer the savage challenges of the streets to the dubious comfort of Boston’s homeless shelters. For Kidder’s readers, Tony’s great company. Big and muscular, he protected homeless women from predators. They called him the Night Watchman.

Tony, it turned out, was sexually abused as a boy by a priest. And beaten. Later, Tony would spend 18 years locked up behind bars for trying to rape a teenage boy.

Naturally, it doesn’t end well.

As we learn, Tony wasn’t any saint. In Kidder’s telling, that role is reserved — though with reservations — for Dr. Jim O’Connell, a deceptively brilliant, Harvard-educated doctor who got talked into starting Boston’s first medical program for homeless people back in 1985. At the time, O’Connell — then finishing his residency — planned to be an oncologist; the homeless gig, he figured, would just be for one year.

Now, nearly 40 years later, O’Connell’s hair has turned a silver white, blowing, as Kidder writes, “like a bit of cirrus in the wind.” He’s still practicing medicine at what has become Boston’s flagship health care program for homeless people. In that time, the program grew from a crew of eight to 400, from a budget of $450,000 to $7.8 million. In the first year, the program served 1,200 patients. Most recently, it exceeded 11,000.

To make all this happen, O’Connell regularly works 110 hours a week. His first two marriages, not surprisingly, went up in smoke. Unlike many who tend to homeless people, O’Connell was not infused by any faith or religious conviction — he is a saint with no god.

Naturally, Tony Columbo and Jim O’Connell crossed paths, becoming friends, comrades, co-conspirators. In a way, family. Tony, it turned out, had a creative eye for administrative improvements. As Kidder noted, Tony discovered a new sense of purpose. O’Connell was smart enough to accept what Tony offered.

He was also self-effacing and smart enough to listen to the nurses who initially took a decidedly dim view of him, assuming he wouldn’t stick around long. One nurse, Barbara McInnis, instructed O’Connell to wash the feet of his patients — and only that — for the first two months. This was no Catholic act of self-abnegation. Diagnostically, the condition of a patient’s foot spoke volumes. O’Connell did as he was told.

Like O’Connell, Kidder is laid back and understated, but also irrepressibly enthusiastic. Like O’Connell, he is not a crusader. “I like characters,” Kidder declared in a recent interview. “I never set out to do a good deed or write about homelessness.” Like O’Connell, Kidder got sucked into the project almost by accident while working on another book about a really rich guy who told him he needed to meet Jim O’Connell. A couple of van rides into the night — during which Kidder watched O’Connell dispense hot chocolate, sandwiches, blankets, socks, and medical treatment to people sleeping on the streets — and Kidder was hooked. He described the experience as being both “scary and fun.”

What made it fun, Kidder said, was the palpable warmth between O’Connell and his street clients. What made it scary was how utterly ignorant Kidder discovered he was — how he’d mastered the art of Not Seeing — this huge alternate reality in his own hometown. At that time, Kidder, in his late seventies, had grown weary of all the ambient “cruelty and chaos and stupidity.” In Jim O’Connell — and nurses like Barbara McInnis — he found a much-needed antidote. “It’s really nice to know there are people out there like Jim and Barbara doing their best to make things better.”

Kidder has a keen ear for conversational exchanges. He keeps them brief. He does not consider himself an expert on homelessness, other than that he thinks new terms such as “the unhoused” or “those experiencing homelessness” don’t do justice to the lethal violence confronting people who live and die — in large numbers — on the streets.

But for all his breezy understatement, Kidder knows outrage. No matter how much they work, people like O’Connell and McInnis and Tony can’t keep pace with the new arrivals. “Is our society becoming more and more feral?” he asked. “I’m worried in a way I never was before. I’m worried about this country,” he answers. “We have a system that relies on the production of human detritus.”

Kidder doesn’t buy the popular theory that then-governor Ronald Reagan created the homeless crisis in the 1970s by shutting down California’s mental institutions. “That’s bullshit,” Kidder said. The real homeless crisis started 10 years later, fed by any number of causes: the recession, AIDS, the crack epidemic, traumatized Vietnam War veterans, gentrification, and the elimination of single-room occupancy hotels. And yes, of course, the lack of mental health treatment. The mental health institutions, however flawed, he said, were built with the best of intentions. “When the system began to falter, we did what we always do; we tore it all down and replaced it with nothing.”

For O’Connell and Kidder, one of the biggest causes of homelessness is child abuse. A psychiatrist who worked with O’Connell estimated that 75 percent of the patients were seriously abused as children. “The stories I heard were just sickening,” Kidder said.

When O’Connell contemplated big-picture fixes, Nurse McInnis discouraged him. “We don’t need to be saints or zealots,” she would say. “Just flawed people doing their jobs.” Or she would ask, “Who are you? God? Your job is to take care of that broke foot.”

For Kidder, the secret to O’Connell’s stamina is hardly a mystery. He served people who desperately needed help and were grateful for what they got. And O’Connell could practice medicine the way he thought it should be practiced. You could take your time with patients. You could not limit yourself to the 10-minute increments that medical bean-counters insisted upon.

O’Connell didn’t see himself as a saint so much as a Sisyphus, forever pushing the rock up the hill. The O’Connell Kidder saw got irritated — though on rare occasion and not for long — and gave himself permission not to like all his clients. But when Tony died from a drug overdose, O’Connell began to worry that he too wouldn’t last much longer. “If you step back, it’s really depressing. But there’s some kind of joy I feel from doing it day to day,” he said. “And that worries me.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.