Dance Review | ‘Sound and Smoke’ Performed at UC Santa Barbara’s Hatlen Theater

Dance Concert Reimagines the Past

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 19th-century play Faust has a line that says, “I have no name for it! Feeling is all: Names are sound and smoke…”

In many ways, this line speaks to the transient nature of names, and with it, human lives. However, as Meredith Cabaniss Ventura’s dance concert, Sound and Smoke, informed us, this line also speaks to the idea that the things we take as fact can always be reframed and reimagined, particularly when looking at how famous female figures throughout history are portrayed and remembered. In this reimagining of the female body that Ventura’s concert explored, many deep-rooted patriarchal modes of thought were brought to light in what was both an entertaining and insightful performance.

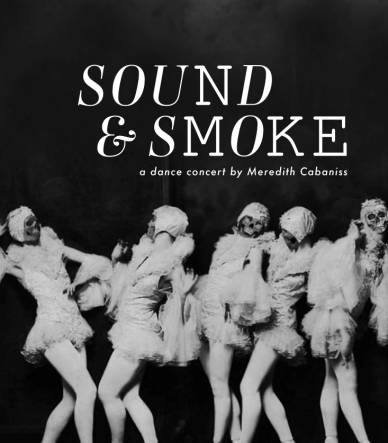

Performed April 21 and 22 at UCSB’s Hatlen Theater by a medley of Ventura’s dancers from her company, Selah Dance Collective, along with UCSB students, the concert was rooted in its inspiration by the Weimar-era cabaret group Schall and Rauch (translated to “Sound and Smoke”), as well as by a series of women in the spotlight who are remembered throughout history for “their tragic and often untimely deaths.”

Ventura notes, “Works like Sound and Smoke have the potential to reframe the past in order to navigate the present … My work represents a different understanding of historical narrative and embodies a radical theory of the body….” Even if Ventura had not provided a detailed description of what her performance was inspired by within her program note, the feeling evoked from the concert would have been more than enough to prompt audience members to consider reframing traditional narratives.

The concert opened with a dancer posing in a way that immediately was evocative of seduction — a bold red dress, a bare leg peeking out through a slit, and a confident demeanor. The genius of this opening is that it points to a major question that Ventura’s concert studies — Why, in so many instances throughout history, is the female body’s worth in performance derived from its treatment as a sexual commodity?

In many ways, by bringing questions such as this one to light, Ventura’s concert has already played a role in shifting the audience’s minds towards thinking about how patriarchal modes of thought inspire the way women, particularly those who are famous historical figures, are perceived.

As the performance continued, Ventura’s choreography displayed a stark juxtaposition between dancers posing beautifully, smiling, and waving to the audience, and then when the scene shifted, to the same dancers looking panicked, shaky, worn-out, and often collapsing and being carried offstage. In this, the idea of women in the spotlight masquerading any mental health issues in order to cater to the public eye was created masterfully.

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Ventura notes that a historical figure who served as a great inspiration for Sound and Smoke was the actress and dancer Anita Berber, who is said to have collapsed on stage in one of her performances, dying several months later at the age of 29. Marilyn Monroe, Virginia Woolf, Eurydice, and dozens of other real or imagined characters throughout history also served as inspiration for Ventura, who notes that a common thread between these characters is that they all “die from various means but their lives and work heavily feature their relationship of their body to patriarchy, and the negative effects of this relationship also define how we see them now historically and culturally.”

Ventura continues, stating, “Nearly all of the women I am referencing in this show are written by men and die by their hand (or pen).”

One especially striking aspect of the show was the incorporation of audio by the poet, Sylvia Plath, reading “Lady Lazarus” aloud. Plath’s writings describe living under public scrutiny, in which she states, “The peanut-crunching crowd/ Shoves in to see/ Them unwrap me hand and foot —/ The big strip tease./ Gentlemen, ladies/ These are my hands/ My knees./ I may be skin and bone…” These lines fit seamlessly into the dance performance, where the dancers evoked the negative implications of being an object of voyeurism.

An interesting aspect of the performance was a dancer dressed in a suit who made regular appearances throughout the span of the concert, often watching the other dancers, clapping for them, and performing minimalist choreography compared to the rest of the group.

This suited figure appeared to symbolize a manifestation of the male gaze or men in power who reap the rewards of women’s hard work and objectification, particularly evidenced by the ending of the concert, where the suited figure smiled, danced, and reveled in the spotlight, while a dancer stood in the background, gasping for breath, panicked, and eventually was carried offstage upon “dying.” In this, the idea of the female body being used by the suited “man” to achieve fame became created — a theme that was drawn across the entirety of the concert.

In Ventura’s enigmatic response regarding what she hoped the audience might take away from the concert, she states, “This work does not intend to lead the audience to one conclusion, per se, but instead, I hope that the audience is able to connect emotionally to the piece in some way. My goal is for the audience to reflect upon their own relationship to their bodies and their ideas, assumptions, and beliefs about how those bodies should appear.”

Ventura’s work in Sound and Smoke is poignant, deeply researched across the span of history, and intricately choreographed, ultimately creating an exciting, unnerving, and thought-provoking experience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.