Stem Cells in Menstrual Blood

They Can Even Become Neurons

One of the major barriers preventing widespread use of stem cells in therapeutic clinics is the great difficulty of collecting a large number of stem cells from any single person. But this isn’t because our bodies don’t have many stem cells; they are, in fact, present in most tissues. Rather, there are few tissues that freely shed their cells on a regular basis and in great quantity.

Consequently, stem cells must often be harvested using an invasive procedure. For example, one of the least invasive procedures is using a needle and syringe to withdraw stem cells from bone marrow, and only so many stem cells can be removed this way.

However, a relatively recently discovered addition to the stem cell family offers a way to overcome this hurdle. Stem cells have been found to reside in menstrual blood, presenting a possible noninvasive manner to obtain large numbers of stem cells from a single patient. These stem cells hold great therapeutic potential for treating diseases and regenerating lost tissues, although much still remains to be learned about them.

Stem cells residing in menstrual blood, referred to as endometrial regenerative cells (ERCs), were discovered in late 2007 and independently reported by two different collaborative research groups. (One group was led by Dr. Neil Riordan, president of MediStem Laboratories and director of the Bio-Communications Research Institute; the other was led by Julie Allickson of Cryo-Cell). In addition to being regularly available and freely released by the body in large quantities, the ERCs also potentially overcome the problem of immune rejection in many female patients, as they could use their own stem cells for therapies.

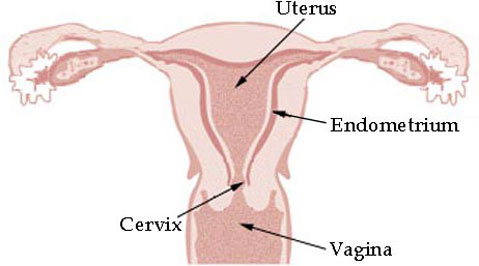

Such incredible findings don’t come out of nowhere; researchers had already suspected that stem cells might be present in menstrual blood because stem cells were previously found in a layer of cells that line the wall of the uterus. On a monthly basis, this layer, called the endometrium, becomes thicker and increases the number of blood vessels and small glands within it to create ideal conditions for nurturing an embryo. However, if embryo implantation does not occur, the early endometrium lining is broken down and shed: menstruation.

Because the endometrium is constantly growing, constantly being broken down and rebuilt, it’s an ideal tissue to investigate for the presence of stem cells; stem cells are masters at creating tissues. The menstrual blood excreted monthly is made up of both blood cells and cells from the endometrium layer. It was first reported in 2004 that stem cells reside within the intact endometrium lining of the uterus. Researchers therefore thought it likely that stem cells could also be found in the shed endometrium. Surprisingly, the stem cells discovered in menstrual blood, ERCs, appear to be different from stem cells living in the intact endometrium.

Stem cells from the intact endometrium belong to a large group of stem cells called mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), but ERCs do not; they make different proteins and can become different types of cells. More specifically, MSCs create a known, large set of proteins. The ERCs (which actually physically appear similar to MSCs) produce some, but not all, of the proteins in the established MSC set. Additionally, ERCs were found to be able to turn into many more types of cells than the stem cells from the intact endometrium. For example, ERCs can become neurons, or brain cells, as well as muscle, fat cells, bone, cartilage, liver cells, and other cell types. Overall, ERCs, were determined to be functionally distinct from endometrium MSCs. Although ERCs do not appear to be MSCs, the stem cell category ERCs best fall into remains unclear, as do several other answers concerning their stem cell identity.

Again surprisingly, ERCs do share some characteristics with embryonic stem cells, producing some proteins that are normally made by embryonic stem cells, and that are quite unusual for cells in the adult body to make. The presence of embryonic stem cell proteins in ERCs, combined with the ability of ERCs to differentiate into a large number of cell types, led one research group to propose that ERCs may be able to become any desired cell type, although other researchers report that their stem cell potential is more limited; overall, much remains to be determined. If the ERCs hold the great promise that some researchers believe they do, they may be a vital resource for future cell-based therapies.

Some reported characterization discrepancies of the ERCs between research groups have led to speculation that there is variability in the quality of ERCs isolated. Since there was not a standard method of isolation in place for these cells, there could be great variability in the actual cells isolated, depending on the specifics of the purification method used. Additionally, the quality of ERCs isolated could depend on the individual donors, possibly related to age or other factors. To complicate the identity of these stem cells even further, it has been suggested that there may be multiple different types of stem cells living in the menstrual blood, not just the ERCs; it may be difficult to be sure of exactly what cell type is being tested.

In addition to questions about their identity, the origin of these stem cells is also still very much up for debate. Some theorize that the ERCs are endometrium stem cells that were shed, though, as discussed above, because ERCs are rather distinct from the intact endometrium stem cells it makes it quite unclear. Other researchers hypothesize that the ERCs are from endometrial glands, as many glands are present in menstrual blood. With a better understanding of the origins of these cells in the body, and potential variability between donors, it will be easier to properly isolate the ERCs for use in down-stream clinical applications.

Though many questions remain to be answered before these newly discovered stem cells can be accurately characterized, a great amount of interest in using menstrual blood stem cells for regenerative therapies has already materialized. Researchers are currently looking into using ERCs for treating neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases and salvaging limbs, among several other applications. Preliminary clinical trials for treating multiple sclerosis in humans using ERCs have already yielded some promising results. Several industries, including the discoverers Cryo-Cell International and MediStem Laboratories, have quickly recognized the great potential of these cells and are not only researching their use in prospective applications, but also offering to cryogenically preserve patients’ menstrual blood.

The significant promise these cells hold as a large reservoir of patient-specific stem cells that can be obtained in a relatively easy manner may make people think twice about discarding any cells that were once a part of their body.

For more on Menstrual Blood Stem Cells, see Teisha Rowland’s “All Things Stem Cell post on Stem Cells Discovered in Menstrual Blood: Endometrial Regenerative Stem Cells” or her “All Things Stem Cell post on Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Diverse Family, Large and Still Growing,” The National Institute of Health’s Stem Cell FAQs, or, for a visual explanation of terms used, see All Things Stem Cell’s Visual Stem Cell Glossary

Biology Bytes author Teisha Rowland is a science writer, blogger at All Things Stem Cell, and graduate student in molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at UCSB, where she studies stem cells. Send any ideas for future columns to her at science@independent.com.