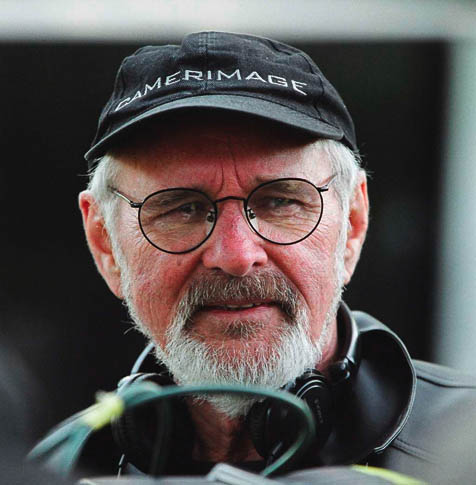

Introducing SBIFF’s Guest Director, Norman Jewison

Moviestruck

What do a celebrated romantic comedy, a finely chiseled caper film, and a socially conscious exploration of racism in the South have in common? A veteran film director whose wide-ranging interests in a half-century in the medium have added up to a body of work with no easy description or pattern. In honor of Norman Jewison’s role as guest director at the film festival this year, there will be screenings plucked from his vast and varied filmography-Moonstruck, The Thomas Crown Affair (the original Steve McQueen model, not the Pierce Brosnan remake), and the acclaimed exploration of racial tension in the South, In the Heat of the Night, with Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger.

Part of what makes Jewison a distinguished American filmmaker is the fact that he isn’t an American. Born in Toronto in 1926 and having lived there for much of his life (splitting his time in Los Angeles), Jewison started out in theater and television before moving sideways, and skillfully, into the movies. To hear him tell it, Jewison always wanted to focus on making musicals-he managed to direct Fiddler on the Roof and Jesus Christ Superstar-but found it hard to get Hollywood interested in the form, and besides, was pulled in other directions.

The socio-political direction has come out in the last decade, with the acclaimed 1999 film Hurricane, starring Denzel Washington as wrongly-accused boxer Ruben “Hurricane” Carter, and, in 2003, the film The Statement, about the hunt for a Nazi executioner.

Jewison was on the phone from sunny Malibu recently. An amicable sort, full of stories and observations, the vibrant octogenarian has been there, done that, and is aiming to do more.

You’re from Toronto, and still based there?

Yeah, I’m a Canadian. I’ve always spent part of my time here, but I lived in Europe for nine years. I started at Universal with Tony Curtis in my first film. Then I did some Doris Day pictures-The Thrill of It All and Send Me No Flowers. And then I did The Cincinnati Kid for MGM, but you know, in 1970, I became discouraged. I’d been through the assassination of JFK and Martin Luther King Jr. and then Bobby Kennedy. I’d been working on both their campaigns and I marched at Martin’s funeral.

I just wanted to get out and I had the opportunity to make Fiddler on the Roof. So I left and went to Europe and I lived there for the next nine years. And that’s when I did Fiddler and Jesus Christ Superstar, and Rollerball, in Europe.

Rollerball is yet another oddity in your filmography, isn’t it?

Yeah, that’s the only film I’ve made that takes place in the future. That was a highly political film and it became a cult film in Europe. In America, they were more interested in the violence of the game. But it was actually about a corporate society. It was a highly political film and I really liked that film. They tried to do a remake of it and I pleaded with them not to make it. But they went ahead and did it, and lost a lot of money.

So you were vindicated, maybe?

I can’t understand why they made that film. But you know, when I look back on my filmography, I’ve never been a genre filmmaker. If someone asked me what my metier is, I really came from musicals. I came from live television. I was doing television specials. I did “Hit Parade,” I did shows with Harry Belafonte, his first special, Judy Garland’s first special, Danny Kaye’s first special. I was more in a musical area. So I’m really at home in that area.

My biggest disappointment was that I never got to make Chicago. I always wanted to make it (laughs). But of course, that was Harvey Weinstein. I get final cut, so he’d never let me do that.

Once MTV came in, when I look back on it, Jesus Christ Superstar was like the first rock video, really. I used a lot of my old television techniques-the stop frame and the zoom lens and all of that stuff. I remember when MTV started, I thought to myself, “Oh boy, I wonder if the musical form in film is going to be usurped now,” and it was. It has never had a chance. We never made too many musicals after that point, Chicago being the one big exception.

And of course, Sweeney Todd this year. The music carries it, in my opinion. That’s the power of the piece. I could have done with less blood, but what are you gonna do?

You really keep up with what’s coming out? Are you still as much a film buff as ever?

Well, we’re lucky that the Toronto Film Festival is huge. 200,000 people come to it. It’s enormous. So I do have the opportunity to participate in that. Then I’ve got the film center in Canada, the Canadian Film Centre, which is like AFI here. So I keep in touch with all the young filmmakers through that.

And I have my offices down here. I’ve got a place in Malibu. I’m still plugging away, trying to make another movie. So I keep in touch pretty well with everything. I spent a little bit of time with Julian Schnabel the other evening. I was just so knocked out by that picture [The Diving Bell and the Butterfly].

Speaking of films based on true life stories, Hurricane was a very moving project.

Yeah, with Denzel. He gave a brilliant performance. That’s about the best performance I’ve ever seen on the screen in a long time. I told him he’ll never get as good as that again. [Laughs.}

Moonstruck was a comedy that resonated on a large scale. Can you sense when one of the films you’re making is going to do that? No, I don’t think filmmakers really know very much about that. Timing is everything in movies. I know that. I guess the audience that year was in the mood for a romantic film. We really pushed the Academy that year. We were pushing and came very close, I think, to winning the award for Best Picture. I remember it went to Bertolucci’s film, The Last Emperor.

But I don’t think any of us really know. I’ve talked to other filmmakers. They’re so worried. Everybody’s so worried-“Gee, do you think anybody’s gonna come?” (Laughs.) Directors suffer a lot.

That’s part of the gig, right? Oh, yeah. I think it’s that you just don’t know. I was worried about The Hurricane. It was a very controversial film, about Rubin Carter and justice denied. It brought out a lot of racism in New Jersey. It was like they were going to try him all over again. But I don’t think any of us really know how they’ll do.

I went to a screening earlier this year. The Academy had a big twenty-year anniversary since Moonstruck came out. It doesn’t feel like it, because it’s around. They keep showing it. People keep talking about it. It’s one of those films that people really felt close to in some way. But they had a big screening in New York last month. It was really wonderful. A lot of people who worked on the film were there, and Olympia Dukakis was there. Cher never showed up. But it was so nostalgic, and it was packed.

You’ve said you’re not really a genre director. Is that by design or by instinct? I think it’s because of curiosity, of wanting to do a particular film. If I’d stayed at Universal, I never would have stopped making comedies, because I was under contract and they just kept giving me comedy after comedy. “Well, this Doris Day movie worked. Do another one, do another one.”

I was fascinated with what Hitch [Hitchcock] was doing. It wasn’t until I got out of that contract and had the opportunity to make The Cincinnati Kid that I could break out and do a drama. It was kind of a melodrama, actually. That was a very important film for me as a director. It showed that I could do dramatic films.

But I still love comedy and I love pictures like Juno. Juno is a wonderful film. Jason Reitman has got a nice touch. He got it from his father, I guess. His comedies aren’t over the top. They’re not slapstick, but they’re more thoughtful.

I must say I love the musical form. Music plays an important part in my films. I love what Michel Legrand did with “Windmills of Your Mind” and the first Thomas Crown picture. It was just fantastic. That was his first American score.

Having been involved in Hollywood for decades now, how have you seen the place and the industry change? I think the last 15 years have seen a big change in the quality of filmmaking from the studio point of view. I think it happened when the studios were taken over by multinationals. When a multinational company takes over a film studio, immediately, company policy and so on starts to trickle down. I think the marketing forces ended up taking over Hollywood. When the marketing forces form the creative production forces, things change.

So they’re more interested in demographics and the bottom line. They’re more interested in profit. In order to make that happen, I think it stifles originality and you get a lot of remakes and films that are obviously created for the merchandising spinoffs and stuff like that. It’s a different approach to filmmaking, and that’s why I think the film studio product started to become boring for the audience, and the small independent films became more interesting. That forced the filmmakers, or the serious filmmakers, to have to go outside the studio system to raise the money to make films.

Robert Altman had been out there for a long time, long before any of the others of us. We all ended up raising money in Europe and other countries and making films all over the place. Take Away from Her: Here’s a young woman, Sarah Polley, making her first film, and it’s brilliant. Look at The Savages. There’s another great one, and so is Sean Penn’s film, Into the Wild. None of these films would have been made by a major studio. They wouldn’t make Diving Bell or No Country for Old Men. That’s the sad thing.

On the other hand, we’re getting some wonderful films, and people are making them with less money, because money has no equation with art. So that’s where I think it has gone. I don’t think Hollywood studios are as important as they used to be.

4•1•1

Norman Jewison will discuss his craft, following a screening of Moonstruck, on Sunday, January 27, at the Metro 4.