Scrap Wood Gets New Life in the S.B. Foothills

The Trees Around Us

Every year, literally hundreds of trees are cut down in Santa Barbara-their limbs, trunks, and branches meeting a cruel and ominous fate with a wood chipper. This march toward garden and driveway filler continues even as area contractors and builders place orders at spots like Home Depot and Channel City Lumber for wood that is, more often than not, grown at large-scale tree farms several hundreds of miles from the South Coast.

With soaring gas prices, a plummeting economy, and a global climate that is, to paraphrase Rob Bjorklund, “feeling a little bit under the weather,” this cost-heavy and decidedly carbon-taxing decision, especially when it comes to hard woods, is becoming a less than desirable option.

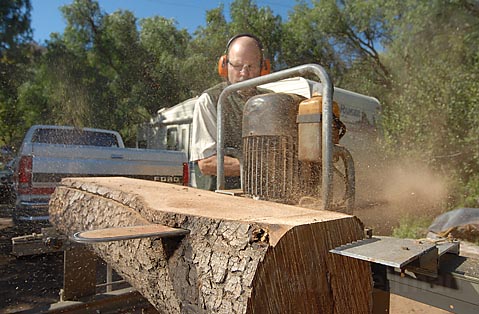

Enter Rob Bjorklund and his wide world of wood in the foothills of Santa Barbara. With a passion for wood that borders on fanatical, the 51-years-young craftsman is single-handedly trying to change the way we think about the trees around us. Covered in sawdust and grinning ear to ear at his Old San Marcos Road sawmill, Bjorklund, gesturing to the lengths of milled and seasoned locally harvested black acacia, walnut, sycamore, and Blue Gum Eucalyptus lumber stacked around his property, opined recently, “This stuff is just everywhere in Santa Barbara, waiting in our urban forest for us to use. Nobody else has the selection like us and the year-round weather to do it.”

The concept of urban forestry is nothing new-the City of Santa Barbara even has its own Urban Forest Master Plan-but the idea of using these trees when they come down, be it from natural or unnatural causes, for custom flooring, bookshelves, countertops, cabinets, picture frames, and even bridges is something that has seldom been done. Until now. Bjorklund, along with a few others like Gaviota-based Seaborn Designs, have been salvaging the fallen wood from our urban forests, saving it from scrap heaps and wood chippers (often thanks to donations from private tree trimming services and the City of Santa Barbara arborists), ageing and milling it themselves, and then turning it into a fully functional (and often artistic flavored) Santa Barbara-grown product.

The end result is an eco-minded and incredibly efficient dance of labor that can actually end up saving people money. “It’s a win-win all the way around,” said Guner Tautrim of Seaborn Designs. “The tree owners win because they get to see their tree go to a good use and they can potentially get a better deal due to the reduced labor costs of the tree-trimming contractor. The contractor wins too because he doesn’t have to deal with the waste and disposal of the tree.” And then, of course, there is the community benefit of keeping the whole process local. All told, it is, as Bjorklund said, “very empowering stuff.”

Certainly there are shortcomings to the process, such as keeping the felled trees cut into sections big enough to be useful and having an organized replanting process in place to ensure that the tree resources remain renewable. (To this end, Seaborn Designs is part of a tree-planting effort on Gaviota’s historical Orella Ranch while the City of Santa Barbara, according to City Arborist Randy Fritz, plants trees at twice the number that it loses each year.) But perhaps the biggest challenge is getting the public to change its basic assumptions about the trees themselves. Take the eucalyptus tree, for example. Prolific throughout the city and the county, these imported, tall, skinny, sweet-smelling, non-native trees are widely considered to be unsafe, unsightly, and completely unuseful.

According to Bjorklund, this bad rap is a classic case of lack of education on the subject. To hear him tell it, the eucs, of which there are some 700 different varieties, have long been celebrated for their hard wood qualities in places like Brazil and Australia, hence the motivation for bringing them to the South Coast in the first place nearly 100 years ago. But the anti-euc movement started when people, most likely harvesting the trees too early and failing to season them properly, found the wood too soft for any real everyday usage. “They developed the reputation then and it has just carried on,” said Bjorklund. “Just about anyone you talk to now says eucalyptus is no good for building anything.”

But at his Old San Marcos sawmill, Bjorklund, following techniques developed decades ago in Australia, has been able to use his onsite solar kiln to season various eucs, even the Blue Gum variety, which is perhaps the most common locally, into flooring-, furniture-, or cabinet-grade hard wood. “The truth is that, when done right, it is really a phenomenal hard wood that we are just throwing away,” said Bjorklund.

And it’s not just the dreaded Eucalyptus that Bjorklund is using in his various custom projects-which included a recently completed new floor for the downtown offices of the Environmental Defense Center-but also black acacia, black walnut, sycamore, ash, live oak, avocado, and others. “There is no telling what type of wood might come to me,” said Bjorklund before adding with a smirk, “or even what it might become.”

4•1•1

For more info, go to localwood.net. For more about SeaBorn Designs, visit loatree.com.