Santa Barbara’s Studio Artists Open Their Doors

The 7th Annual Open Studios Tour

Francine Kirsch likes to keep herself surrounded by women. Her Goleta home is full of them. They stand in stately nakedness on her mantelpiece, curl up in yoga poses on her bookshelves, and dance across plates in her kitchen. Some of them populate soap dishes; others rise up between petunias in the back garden. And one tiny, voluptuous woman hangs from a cord around Kirsch’s neck.

These aren’t living women, of course, but women of Kirsch’s creation, made from clay and stone. Like Eve herself, they are studies in femininity, prototypes of woman. They range in size, in color, and in posture. Many are missing heads, or arms. But there’s one thing they all share in common: curves.

“I’m always looking for the right curve,” Kirsch explains, ushering me into the two-car garage that doubles as her studio. Low tables are lined with bowls and vases, plates and figurines. Some take the shape of seashells, but most carry the form of the female body.

Along with 40 other artists, Kirsch is preparing to open her studio to the public as part of the Santa Barbara Studio Artists (SBSA) 7th annual Open Studios Tour, which takes place over Labor Day weekend. She has a lot of work to show-so much that she’ll erect a tent in the back garden to house the overflow-but curious visitors will want to explore the studio itself, where magazine clippings, postcards, and photographs line the shelves and paper the walls like silent clues to Kirsch’s inspiration. Fashion models vie for space with cartoon jokes, lines of poetry, images from nature, and an odd assortment of knick-knacks; Kirsch says she can’t remember why half of them are there.

It was 1975 when Kirsch moved to Santa Barbara from her native France. She didn’t speak English at the time, but she enrolled in an adult education pottery class where she began to learn the language of clay. More than 30 years later, her English is good, but Kirsch is at her most fluent when speaking with her hands. As we move past her pieces, she often reaches out to touch them, at one point taking my hand and guiding it to a piece of polished, pink alabaster, shot through with veins of white and orange. “You have to feel it,” she said.

From a foundation in clay, Kirsch ventured into stonework, and she speaks of “the challenge of discovering the sculpture within the stone.” More recently, she has begun to explore lost-wax casting with bronze. She shows me an unfinished bronze piece: a female figure standing in a deep lunge with her arms stretched above her head. “It’s warrior one,” Kirsch says, referring to the figure’s stance in a yoga pose. Kirsch herself practices yoga, and her musings draw a connection between that practice and her sculptures. “You do something, and it’s never perfect,” she explains. “There’s always room for improvement. I’ve never made the perfect bowl.”

As for why the shell and the female form carry such appeal for her, Kirsch is happy to leave it a mystery. “You know, I’m still asking myself why,” she says. “I think it’s the curves, and the spirals.”

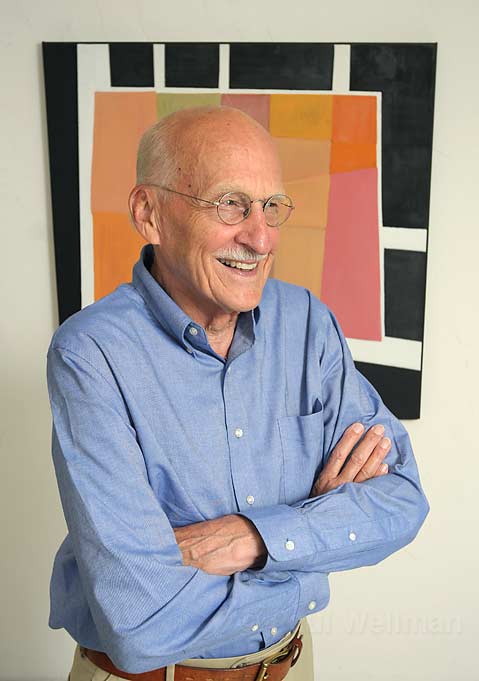

For printmaker John Moses, mystery lies in not knowing exactly what will emerge each time he draws a printing plate away from the paper. Moses worked as an interior architect and designer for many years before retiring to Santa Barbara in the 1980s. On August 30 and 31, his modern, southwestern-style house on the Riviera will be the venue for an extensive display of his abstract, geometric paintings and monotypes-original prints made from acrylic forms.

Moses remembers becoming acquainted with printmaking in courses with Tony Askew at Westmont College, and today cites Askew as among the most influential of his teachers. “I thought printmaking was a waste of effort at first, because I didn’t know how to do it,” Moses says, grinning. “As I began to do more and more, I developed my own technique. I liked the surprises you’d get from a print.”

Although all his larger scale works are acrylic paintings, Moses gets most animated when talking about the smaller, more detailed prints. Using plates of Plexiglas with acrylic cutouts laid on top, Moses paints the plates with printing ink before pressing them onto paper. He never cleans off the ink left on the plate from the previous printing, ensuring that something unexpected will come through each time. Picking up a 10″x10″ monotype titled “Morning Song,” Moses explains, “There are traces from the past in there.” Reddish orbs float atop a grayish, mottled ground; you can pick out the outlines of earlier prints that exert their influence here. In other prints, Moses uses a palette knife to push the paint into ridges and blobs. “Little shifts happen when you being to push and suddenly amazing things happen,” he says excitedly.

Among the many works Moses will have on display are a couple of Mark Rothko-esque, meditative watercolors, a print series of cylindrical containers, and a collection of unframed prints for those shopping within smaller budgets. His architectural background clearly informs his work-there’s an emphasis on lines, grids, and geometric forms, and a restricted primary color palette reminiscent of modernists like Piet Mondrian. And, in a nod to his early design days, Moses will include among his works a plywood chair he first envisioned while at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1953.

What excites Moses most-and what will no doubt strike viewers-is the blend of control and surprise present in his prints. “It’s always a combination of what’s gone before with the new elements,” he explains. “Each print is unique; none of them can be copied.” It’s not what one might expect from a print, and Moses is glad to be a little different. “I guess I’ve never been one to follow the routine or the process,” he says. “I did the process, but I did it on my own terms.”

If there’s any artistic genre that’s based on the redefinition of its medium, it is found object art, and Barbara Baker McIntyre knows all about it. The studio behind her house in the Carpinteria foothills is lined from floor to ceiling with deep, tall shelves. On those shelves are boxes, and in those boxes are the objects McIntyre uses in her work. One is full of old-fashioned shoe forms, one of broken watch parts, and another of feathers. There are dice and game pieces, rusty gardening tools, antique books, baby dolls, and Mexican Milagros. When I arrive, she’s in the middle of shellacking the background of a framed piece that incorporates exotic papers, pieces of mother-of-pearl from a broken bracelet, buttons, and porcupine quills to create a miniature Japanese kimono. This piece and many more will be on display during the Open Studios Tour.

McIntyre grew up in Santa Barbara, attending Cleveland School and graduating from UCSB with a bachelor’s degree in fine art, but she didn’t discover collage work until the mid ’90s. “I started making things, and I just couldn’t stop,” she remembers. Over time, her penchant for combining various elements on the page began to take on three dimensions, and eventually McIntyre realized she was doing assemblage, using a variety of objects not intended as art materials to create whimsical, fantastical works.

These days, the artist spends about half the year working in assemblage, the other half working in wax encaustic-a kind of halfway house between painting and sculpting. Encaustic paintings hang on the walls above her work desk, while the flat spaces are dominated by an unlikely mishmash of objects: a well-worn leather rifle case, the blade of a shovel, and a female dress form encrusted with rhinestones and cookie cutters.

As we slowly circle her studio, McIntyre points out some of the recurring themes in her work. “Creatures and animals comes easily to me,” she notes, stopping beside a sculpture of a whale, with a rusty hoe for a tail, the heel of wooden shoe form for a head, and an old paint scraper for a jaw. Its body is made from a tangle of fishing wire strung with beads, buttons, and medallions. In another corner of the studio is a cabinet that stands on stuffed deer legs, with a roulette wheel at its center and antlers sprouting from its head.

Some of McIntyre’s creations are comical, some are slightly disturbing, and others are more formally compelling, like a framed piece that incorporates antique books with their pages folded into complex patterns. A nearby work-a four-legged box made from 19th century piano keys-looks like a reliquary for some long-forgotten composer.

McIntyre says she culls her materials from a variety of sources, including thrift stores, flea markets, and eBay. She also trades pieces with other artists who work in assemblage. Once she discovers a new object, it may sit around for years before inspiration, or the right combination of items, strikes. “If I’m in the middle of working and I’m in a hurry, I’ll just stash it somewhere,” she admits. “Some artists are much more pristine.” But McIntyre’s work isn’t about tidiness and order; it’s about surprising unions and disconcerting-sometimes even shocking-results. For this artist, it’s about finding a new role for these many discarded objects, and seeking the combinations that breathe them back into life. “I see something,” she says simply, “and I know what it needs to be.”

4•1•1

The 7th Annual SBSA Open Studios Tour takes place Saturday, August 30, and Sunday, August 31, from 11 a.m.-5pm. Tickets cost $20 and are available online at santabarbarastudioartists.com, where you can also view samples of work by all 41 artists represented in this year’s tour. The price of the ticket includes entry to a gala reception at the Arts Fund on Friday, August 29, from 6-9 p.m. For more information, call 899-8854.

To see more of Kirsch’s work, visit francinekirsch.com, and to check out more of McIntyre’s creations, go to mctra.com.