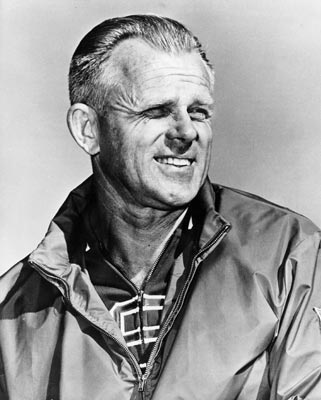

Goodbye Payton Jordan

Legendary Track Coach and Mentor Dies on February 5

I saw Payton Jordan for the last time at a track-and-field meet six months ago. The old coach was 91, and cancer had whittled him down to the leanest sinew and bone. Yet his smile was still bright, and his handshake was firm. That was not surprising. He had always preached and practiced a life of vigor.

He had spent almost a decade of active retirement in Santa Barbara. He showed up at the City College track, dispensing advice and encouragement to young athletes. He inspired his peers at Vista del Monte to work out at the community’s fitness center. He bounced back from a bout with cancer a few years ago and cared for Marge, his wife of 67 years, in her failing health. After he lost her, he decided to move on. He said farewell to his Santa Barbara friends in June of 2007 and relocated to Laguna Hills, closer to his daughters and grandchildren. Payton Jordan died there last Thursday, February 5.

Obituaries heralded his life of accomplishment: an outstanding sprinter who also played some football at USC; an esteemed coach at Occidental College and Stanford University; the head coach of the record-shattering U.S. men’s track-and-field team at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968; a pioneer in masters athletics who set world records into his eighties, earning himself recognition as “The Silver Streak.”

It was at the U.S. Olympic Trials in Eugene, Oregon, that I saw Coach Jordan last summer. That meet was considered one of the finest ever staged in this country, attracting 167,000 spectators to eight days of competition. Most of them were not old enough to remember the meet that was the greatest of all in its spectacle and emotional impact: the 1962 dual meet between the United States and the Soviet Union, a two-day event that put 155,000 people in Stanford’s stadium and drew a nationwide television audience. Payton Jordan was the mastermind of that show, which ended with Americans and Russians spontaneously parading arm-in-arm around the track, a significant thaw in the Cold War.

Jordan was a uniter in the world of athletic competition. “The best thing about sports is the relationships and friendships that evolve,” he told me. “Somehow you touch them, and they touch you.” He counted the Soviet coach Gavriel Korobkov and the Greek marathon runner Stylianos Kyriakides among his best friends. His ability to nurture mutual respect was evident in his lasting relationship with Tommie Smith and John Carlos. They were scorned by many for their symbolic protest at the 1968 Olympics, but their coach stood by them. “I’d defend them ’til hell froze over,” Jordan said. “They were part of the team. They did their job. They competed like champions.”

Jordan’s influence speaks most loudly in the lives of the men and women he mentored. One of them was Kenny Kring, a multitalented athlete from Santa Maria. After competing at Stanford in the early ’70s, Kring stayed on as an assistant coach for a couple years. Now he is a managing director at Korn/Ferry International, an executive search firm.

Kring brought his family out from Philadelphia to visit Jordan in Santa Barbara. “He always remembered the kids’ names, where they went to school,” Kring said. No fewer than 14 of his former athletes- not including Kring-named their children Payton or Jordan. “He had tremendous people skills,” Kring said. “Not a day passes that I don’t think about him.” He could recall the time the coach embraced him after he finished second in a hurdle race against USC and whispered in his ear, “Tuck in your shirt, Tiger-you’re on national TV.” He might have bristled at the time, Kring said, but “those memories have been replaced by a timeless, enduring sense of integrity, self respect, and personal accountability. Coach Jordan was quite a remarkable man.”

GAMES OF THE WEEK: Romantic couples can do some heavy breathing Saturday (Valentine’s Day) by entering Romeo’s Relay, starting at 9 a.m. at the UCSB Lagoon. Each partner will run two miles. There will be a four-mile run for soloists at 8 a.m. . . . Another bonding opportunity is Date Night at the Dome, a two-for-one ticket promotion for UCSB’s men’s basketball game Saturday night. (Print out the coupon at UCSBgauchos.com.) On the floor, the Gauchos will be courting big trouble against the Cal Poly Mustangs-the losing team will be relegated to the Big West cellar. : Westmont College will host rival Biola in a women’s/men’s double-header next Tuesday (Feb. 17).