Carpinteria Beats Back an Epidemic

How One Small City Took a Stand Against Childhood Obesity

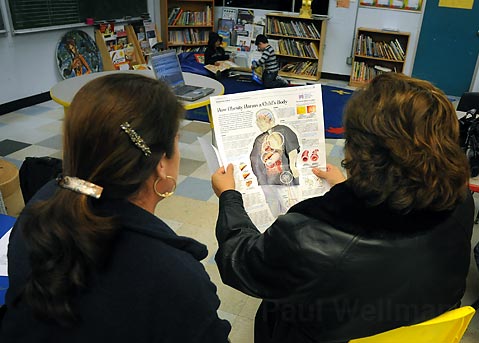

Sandra and Alexandra Valdez are 14-year-old identical twins with all the interests and hobbies American girls their age have today. They hang out with friends after school, listen to their iPods, and on the weekends they go to the mall. There’s even some talk about a boyfriend or two.

Two-and-a-half years ago, there was another, less healthy characteristic they shared with a portion of American youth. They weighed 160 pounds each, 40 pounds overweight.

Considering their lifestyle at the time, it’s not surprising they were so heavy. Their lunch at school consisted of pizza and soda. Their morning snack was chips. After school, they watched television, munched Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, and drank soda. They didn’t like being fat, but didn’t think they could do anything about it. Their mother, Maria Gutierrez, also was overweight-and worried. Both her husband and her father have Type II diabetes, the genetic, life-threatening condition that’s often triggered by excess weight.

But this is not a doom-and-gloom story. It’s a success story, actually, about the quiet efforts of a Santa Barbara doctor and his staff to keep today’s children from becoming the first generation of kids to have shorter lifespans than their parents. And that’s not a scare tactic. Though the steady rise in the number of obese children in America apparently has plateaued, the numbers are still frighteningly high compared to what they were 20 years ago. A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey taken between 2003 and 2006 found 15.5 percent of kids between 2- and 19-years-old were overweight and 17 percent were obese. Santa Barbara’s quotient of overweight and obese children is statistically equivalent. David Pettitt, the acclaimed diabetes researcher at Sansum Diabetes Research Institute, measured the height and weight of 2,701 Santa Barbara high schoolers in 2005 and found that 14.9 percent of boys were overweight and 15.9 percent obese, meaning that 30.8 percent of high school boys in the county had a weight problem. High school girls were slightly better off, with 16.6 percent overweight and 10.6 percent obese.

The Doctor Is In

Michael Fisher, a Santa Barbara kidney specialist, was watching the numbers of obese and overweight kids go up throughout the 1980s and ’90s, both in medical journals and in his clinic, where very young children began exhibiting obesity-related conditions normally seen in adults-things like high blood pressure, arthritis, and Type II diabetes. Knowing that Type II diabetes damages the heart, kidneys, eyes, and nerves and can trigger a stroke and require the amputation of limbs, Fisher would not stand idly by, especially because he knew that Type II diabetes is entirely preventable. In a stage doctors call “pre-diabetes,” when blood tests show the body starting to become resistant to insulin, an 8- to 10-percent reduction in weight plus a regimen of moderate daily exercise in the majority of cases can permenently fend it off. Fisher also knew that at $260 billion a year, the cost of treating diabetes-related complications, such as end-state renal disease and heart disease, poses a dire financial threat to the American healthcare system. If the number of diabetes cases doubles in the next decade as expected, that price tag is going to jump to a half-trillion dollars.

So, in 1999, Fisher founded the Diabetes Resource Center (DRC) of Santa Barbara County, a nonprofit operating above the Artificial Kidney Center at 1704 State Street. Its mission is to reduce the alarming increase in Type II diabetes and other obesity-related diseases in Santa Barbara kids and families by promoting healthy lifestyles. From the beginning, Fisher wanted to focus on low-income Latino families because they’re genetically prone to Type II diabetes, as are African Americans and a number of other ethnic groups. But the double whammy for Latinos as well as African Americans is that the majority of them live in neighborhoods that make healthy living a stretch-areas rich in fast-food restaurants, poor in supermarkets that sell fresh produce, and lacking in parks where kids can exercise safely.

DRC’s first project was at Our Lady of Sorrows Church, a predominantly Latino parish. Fisher began by addressing the congregation on diabetes and the risks associated with excess weight. He set up a clinic in a church office where parishioners could have their body mass indexes (BMIs) and blood sugar checked after services. The program, Esperanza, ran for a year, and though Fisher felt it was positive, he decided he needed to reach kids and families earlier. So he and his staff went back to the drawing board and came up with the Carpinteria Childhood Obesity Prevention Initiative (CCOPI).

The Little City That Could

If it takes a village to raise a child, then it takes a small city to reverse an epidemic in children’s health, and that’s exactly what’s happening in Carpinteria.

The DRC’s new Carpinteria project got $150,000 from the California Endowment, a foundation the state made Blue Cross of California create when it decided to convert from a nonprofit to a for-profit organization. Dedicated to promoting Californians’ health, the grant funded the DRC to teach healthy lifestyles, after-school programs, and an intervention class in a Carpinteria elementary school in fall 2006. Fisher thought Carpinteria was the perfect laboratory because 66 percent of the children are Latino and poor, and the city is small enough that the entire community could take part in the project. Canalino Elementary was chosen because 37 percent of its kids were either overweight or obese, Fisher said, and most of the families lived in the affordable housing projects Dahlia Court and Camper Park-developments out of walking range of supermarkets. Furthermore, 70 percent of the residents have no car.

The initiative was supposed to begin with 80 kids in programs at Canalino, Dahlia Court, and Camper Park, and have an eight-week intervention class called Salud y Bienestar (“Health and Well-Being”) for kids with BMIs higher than the 85th percentile and their parents. (Parents were included because children could not make any true lifestyle changes without them. Besides, many of the parents were overweight as well.) But the number of kids and scope of the program quickly ballooned. The California Endowment asked for a promotora de salud (health promoter) feature, in which members of the community would be trained and deputized to provide peer support to Salud y Bienestar families. Many rural Mexican villages out of range of medical care have a promotora de salud who provides advice and traditional remedies. The concept here would be similar, and immediately five women signed up. By December 2008, 12 women were serving at promotoras, half of them mothers who’d attended the Salud y Bienestar class with their child and wanted to reinforce what they’d learned and learn even more.

The California Endowment also wanted a gardening element, so DRC designed a program based on Berkeley’s Chez Panisse garden project.

The program began with a kickoff town hall meeting at the start of the 2006 school year. Much of Carpinteria was there-students and their families, educators, Rotary club representatives who’d donated money, and businesspeople.

The meeting was needed not only to introduce the project to the community but also to explain how the environment affects a community’s health, said Andria Ruth, a pediatrician at the Westside Neighborhood Clinic and medical director of the CCOPI. Before the evening was over, several Carpinteria businesses had volunteered to help. Ed Van Wingerden of Ever-Bloom Nursery built all the raised beds for Canalino’s garden, All Around Irrigation installed its irrigation system, and Carpinteria Valley Lumber furnished the wood. One Carpinteria farmer still makes complimentary weekly deliveries of fresh vegetables to Camper Park and Dahlia Court.

Priscilla Hernandez is a veteran physical education teacher and executive director of DRC. She designed Canalino’s after-school PE curriculum, runs all the project’s after-school programs, and is in the process of bringing a similar project to Santa Barbara’s Franklin Elementary School. In fall 2006, the after-school program began with Hernandez and Ruth weighing and measuring all of the kids to calculate their BMIs. Of 115 measured, 25 were in the 85th percentile. They were referred to physicians. Then, by letter and personal visitation, these kids and their families were invited to join the upcoming Salud y Bienestar class.

10,000 Steps

Maria Gutierrez received invitations on behalf of Sandra and Alexandra. She and her family live at Dahlia Court. She wasn’t offended, she said. The girls don’t recall being hurt or frightened, either; just excited, as Sandra remembered.

The first night of the class, everyone got a pedometer, a small, beeper-sized gizmo that clips onto one’s belt and counts every step taken in a day. The goal is always 10,000 steps, but many kids go higher. Siblings compete with one another and turn it into a game. The twins couldn’t get to 10,000 at first, but pretty soon they were blowing past it.

Salud y Bienestar evenings were divided evenly between nutrition and physical education. Nutrition lessons included things like how to read food labels, why fruits and vegetables are important, and how to cook low-fat versions of traditional meals.

Because there were so many kids in Canalino’s after-school program, Hernandez split the group in two; half would receive the traditional academic tutoring that Canalino always offered while the other half got DRC’s program. Like Salud y Bienestar, Hernandez divided the kids’ time evenly between nutrition and fitness, part of the “Move More, Eat Less” principle.

Unfortunately, Canalino students younger than the 4th grade weren’t included in the original grant, so they stayed in a classroom all afternoon while sounds of the older kids’ fun carried in on the breeze. Hernandez and Fisher had trouble accepting this and soon went looking for funds to bring the younger children into the program. Fortunately, Cottage Hospital Foundation came through with the requisite dollars. To help teach the additional PE classes, UCSB, Westmont, and Santa Barbara City College students were enlisted for experience and a stipend.

The kids loved the program, Hernandez said, and improvements to their physical condition were evident in a matter of months. Ruth said the highlight was growing and harvesting vegetables, particularly the day the kids made lettuce wraps with tuna and chicken for everyone. At the end of the grant period, 70 percent of the after-school kids had a normal weight, whereas only 66 percent did so in the beginning. Plus, fewer students were at risk of being overweight-that is, five or six pounds over what is considered normal for their height.

Canalino Principal Sally Green said healthy eating is part of the school culture now. Kids point out healthy foods. She knew the shift was complete the day a child’s mother saw her coming down the hallway and abruptly hid a plate of cupcakes behind her back.

According to Green, since 2006, the decline in the number of obese kids at the school is remarkable. “Now, I can think of one boy who is a little overweight and one younger girl,” Green said.

By March, Ruth and Hernandez were confident enough with what they were doing at Canalino to take it into Aliso, the other Carpinteria elementary school. This expansion also was funded by the Cottage Hospital Foundation. A second garden went in, college students were rounded up to help teach PE, and the ritual weighing and measuring began all over again.

One evening, when she was picking up her daughter from Aliso, Guadalupe Rodriguez, 28, noticed the Salud y Bienestar families playing with hula hoops in the yard. Stopping to watch, she and her daughter Mariana, a 5th grader, wondered what kind of class it was. Neither Guadalupe nor Mariana were overweight, per se, but they were both at risk of becoming so. More than that, Guadalupe wanted her family to learn how to play outdoor games together. She and her family-who live on the ranch in the Carpinteria foothills where her husband works-weren’t regular exercisers. So Guadalupe, Mariana, five-year-old Geraldo Jr., and Geraldo Sr. enrolled in last summer’s session of Salud y Bienestar.

A Brigade of Promotoras

One rainy night last December, the Dahlia Court apartment complex glowed with colorful lights. In a portable classroom all the way to the back, eight Latina women, all of them promotoras de salud working for the CCOPI for small stipends, were enjoying the final class of a 16-session health-and-wellness course. After a guided meditation, the women gave reports on an aspect of health they had researched: among them, postpartum depression, the health risks of obesity, and cholesterol. Each one had been assigned a Salud y Bienestar family to guide and encourage during the eight-week course.

“If you’re talking about the Latino population, people are much more likely to believe what their neighbor tells them than what you hand them on a piece of paper,” said Ruth. “People [see] them, their faces, the way they look, and they say, ‘What do you have that I want? I want to do what you’re doing.'”

Elizabeth Torres is a tiny woman with oversized enthusiasm for the changes she’s made in her family’s lifestyle. A year-and-a-half ago, she walked past the room where the first promotoras held their meetings and ultimately poked in her head to find out what they were doing. Soon she was one of them. Torres, who worked at a Burger King in both Lompoc and Santa Barbara for 11 years but is now a stay-at-home mom, has lost 24 pounds.

Maria Valdez is now a promotora, too. But when she and the twins were taking Salud y Bienestar, they hardly needed their own promotora, because they proceeded to the front of the class on their own. By early 2007, just four months after receiving their fateful invitation, Sandra and Alexandra were down to 120 pounds. They have maintained this weight. Initially, it was difficult to watch the other kids eat Doritos when they couldn’t, Sandra recalled, so they just tried not to look. Today, they don’t watch Nickelodeon or soaps after school. Instead, they take long walks with their friends or with their mother. They say their life is “funner” now. They’re more outgoing, and they have confidence to approach people and to go to parties. Their grades and study habits have improved, too, they said.

As for Maria, she has lost 25 pounds. She bakes the dishes she previously fried, uses less oil when she does fry, and incorporates more vegetables.

According to DRC surveys, 90 percent of Salud y Bienestar participants increased their physical activity after taking the class and 100 percent made at least three changes in their family’s nutrition and fitness practices. Guadalupe Rodriguez made more. She reads labels in the grocery store now, looking out for trans fat, sodium, and high calorie content. She stopped serving soda with dinner. Almost every weekday evening, the family plays some physical game together outside. Substituting popcorn for the Flamin’ Hot Cheetos Mariana loved to eat after school and limiting TV was the most challenging. Mariana admitted she cried at first. Guadalupe remembered her being grumpy and angry. Geraldo Jr., a mountain of energy, adjusted easily. Yet, six months later and six pounds lighter, Mariana is happy. She feels healthier. “I can’t describe it, but I feel comfortable,” she said. “It’s good to be healthy and to exercise, like, every single day.”

Though the Carpinteria Unified School District (CUSD) initially was skeptical of the DRC’s capacity to sustain the program, it now contracts the nonprofit to continue the after-school program at Aliso and Canalino. With college students helping to teach PE, the cost is modest. Ruth said the program has become self-sustaining.

Paul Cordeiro, CUSD superintendent, said there’s a point where wellness and academic success intersect. “When considering the concept of wellness and its connection to academic success, [you have to] assume kids are less supervised and less nurtured than they were a decade ago,” Cordeiro said. “And that has to do with the stressors of society.”

Michael Fisher is just getting started. This fall, a new obesity prevention program began at Franklin Elementary in Santa Barbara. And it’s going to be incorporated into the school day proper. A garden already has been planted and the BMIs of 474 students in kindergarten through 6th grade have been taken. Ruth said 22 percent of them were at risk for being overweight, and 31 percent were overweight. Cleveland Elementary is next on the list, but ultimately DRC would like to take the program into far-flung areas of the North County.

But Fisher is thinking even bigger than that. Knowing that the prenatal period provides the best shot at influencing kids’ health, his new goal is to educate new and expectant mothers about breastfeeding and eating well. The DRC just opened an Early Wellness Center in Carpinteria’s old Main School, which was recently purchased by a consortium of Santa Barbara foundations for centralizing programs for families with young children. DRC’s Early Wellness Center in the new Carpinteria Collaborative includes a classroom with a kitchen that opens out to a garden and a wood floor for exercising.

And Fisher wants to put fruit and vegetable carts on Milpas Street, just like Manhattan hot dog vendors, so low-income families can have easy access to affordable produce.

“You know, it’s like loading the bus,” Fisher said. “We got the college students coming down [to help], we’ve got the promotoras from the community, we have a lot of other people. : So this is the goal, to empower every community.”