The Last Man in Paradise

Forest Service Finally Forcing Tom Merkel to Leave His Paradise Road Cabin

Time is nearly up for Tom Merkel.

In an oddly uneven and crumbling cabin – Santa Barbara’s oldest, he claims – Merkel is the last holdout in a community of 27 cabins off Paradise Road and across from Paradise Park in the Santa Ynez Mountains. His “recreational residence” lease, which has allowed the cabin to occupy U.S. Forest Service land for almost 100 years, is finally up. Merkel was asked in November to vacate the cabin, which, after nearly a century of occupation, now faces demolition.

Long overlooked by the Forest Service, which Merkel says has been very kind up to the point of eviction, the cabin breaks countless building codes. “They let it all slide year after year,” says Merkel. “They always figured it was about to be torn down.”

Now it finally is.

As of his move-out date, however, Merkel remains. He believes he has one last hope for preserving the cabin – its strong historical value to the Santa Barbara area – and he is making his last stand. He held an open house on Saturday, April 4, to let the public get a look at his cabin and its grounds, littered as they are with remnants of California’s past.

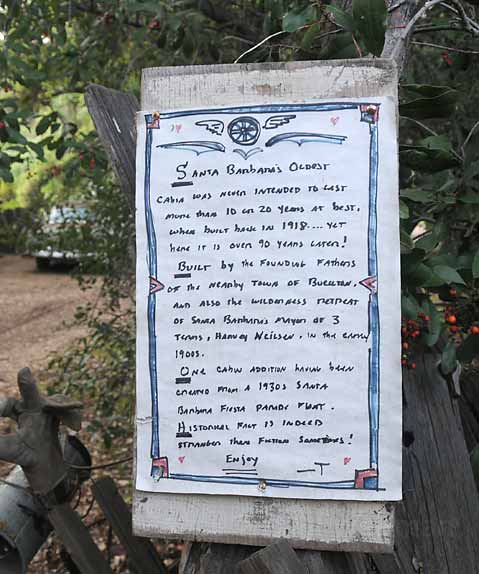

At least part of the cabin was built in 1918 by Wylie C. Nielson. In Merkel’s estimation, that was the year the cabin began. Originally built as a one-room hunting lodge for the Nielson family – whose undeniable roots in Santa Barbara history include the mayoral terms of Harry Nielson from 1918 to 1935 – additions have been made over the last 91 years, with rooms added by various owners over the cabin’s lifespan. “It’s a cultural Frankenstein,” laughs Merkel. “It’s not Martha Stewart. It’s a little bohemian.”

Is it ever. With many windows missing, and piles of unused appliances, tangled and busted guitars and broken sofas obstructing much of the interior, it’s not so easy on the eyes in the first walk-through. One of the rooms is actually built out of an interwar Fiesta float designed for WWI veterans, complete with unflattering cartoons of the Kaiser. From the outside, one can clearly see where one era in building ended and the next began. It was a shaky-handed surgeon who put the pieces of Santa Barbara’s oldest cabin together.

Yet the Merkel estate is, unquestionably, one of a kind. “My commitment,” says Merkel, “is to history.” He believes Santa Barbara will have lost an important tie to its past if the cabin is destroyed, and he has been fighting its demolition for years. Now, as the last day of the cabin’s life may be approaching, he remarks, “I’m willing to go to jail over principle.” He adds with a grin, “Plus, it will look good on my resume.”

Merkel claims to have found himself in the Santa Barbara area shortly after his business partner died at sea. He purchased the cabin not from the Nielson family, but from a man named Baird Caswell – “the second cousin,” Merkel claims, “to Nelson Rockefeller.”

And while Nielson family representative Michael Collins said the family would love to see the cabin survive, that’s not why the leaning structure is so dear to Merkel. It is rather the clutter in and surrounding the house – not the clean, guided-tour history of a museum, but the well-used and authentically worn leftovers of a society that moved from one era into another – that Merkel does not want to see swept away. Merkel, and the cabin’s previous owner Baird “Rockefeller” Caswell, have compiled the physical history of California’s last 50 years in rusting chassis, bathtubs, and streetlights.

Towering sculptures made from scrap metal stand surrounded by scrap metal. Stoves and pianos, road signs, washing machines, and motorcycles fill the grounds. One can track the progress and abandonment of suburban culture in Merkel’s backyard, and in the “rescued” decommissioned fixtures of a changing society.

His passion and his hospitality emphatically genuine, Merkel revels in public interest and is quick to welcome visitors. He tells the story of one urban family who were pulled off the road by the irresistible allure of Merkel’s signs promising: “Santa Barbara’s oldest cabin!” and “Folk Art Magic Museum!” While touring the grounds with astonishment, the smallest member of the family cried, “Dad, I thought Hobbit-houses were for pretend!” Merkel says he could think of no good reason to set the kid straight.

His unique historical sentimentality can be seen in what Merkel calls his “other place” or his “gigantic cultural time capsule” – a car museum in the Cuyama Valley. Consisting of more than a thousand automobiles from the past hundred years, it is a monument to abandonment and lost history. Merkel is a collector, in the most basic and inclusive sense. He recently “rescued” the towering Frosty the Snowman from Santa Claus Lane, giving it permanent residence keeping watch over a sea of old Buicks, Cadillacs, and Lincolns.

Josh Fields, great-great-grandson of W.C. Fields, says his family has been in Santa Barbara for generations and long ago befriended Merkel. He commented on what seems to be a grave behind the house, marked with a WWII American G.I. helmet and the name “Fergusen,” asking: “Tom, is there someone buried there?” Merkel frowned in thought and answered, “No one I’ve buried.”

In fact, most would find the word “crackpot” irresistibly intruding behind any impression of Merkel. But as the sweet vagabond scent of beer permeates the dank and musty corners of his estate, his love of all things abandoned and faded from memory becomes contagious. One becomes hopelessly charmed by Tom Merkel – steward of the unconsidered refuse of California history. A Don Quixote in the mountains in a battle without a villain, Merkel and his antiques are victim to the inevitable expiration of contractually allotted time.

The Forest Service, no heartless corporation, regrets the need to remove the cabin. “It’s very unfortunate,” said Kyle Kinports, Forest Service representative, of the hard task of evicting Merkel. “It’s a very special place for him.” The fact is that the Forest Service has had a plan to remove the cabins since 1970. “We have to provide a minimum of 10years notice before we evict anyone,” Kinports said. And they did.

So what’s next for Tom Merkel? He says that when the house changed hands between he and Caswell, “Baird packed two bags and left it all behind.” This exit always appealed to Merkel, who believes everything donated by others and “rescued” by him belongs now to the house. “If I go,” he says with a sad smile, “I’m only packing two bags. Like Baird.”