King of Clubs, Hogs, and Trash

Remembering Otto Hopkins, the Most Important Santa Barbaran You’ve Never Heard Of

Otto Hopkins may be the most compelling figure from Santa Barbara’s past that nobody’s ever heard of. An African American endowed with a mythically large personality, Hopkins ran The Cotton Club, a successful Haley Street nightclub where multiple ethnicities drank, danced, and carried on together. This carrying-on took place in the 1920s and ’30s, a time in American history when Jim Crow laws and segregation were still enforced with terrifying results by lynch mobs in other parts of the country.

In 1935, after a 10-year run, The Cotton Club was shut down when Santa Barbara mayor E.O. Hanson got in a headline-grabbing street brawl with a fellow night-clubber who’d made disparaging remarks about a red-headed woman keeping the mayor company that night. Santa Barbara’s daily paper, the Morning Press, would refer to The Cotton Club in its reports, almost without fail, as “notorious.” Hopkins would soon open a Cotton Club II, but this one was in Boulder, Colorado. Hopkins wanted to serve the vast army of construction workers, many of whom were African-American, assembled to build the Hoover Dam.

In Santa Barbara, he opted a to open a fine supper club, The Brown Derby, where The Cotton Club used to be right across from St. Paul’s Church on 400 block of East Haley Street. However toned down this club was, business cards for the Brown Derby still proclaimed it a place to “Eat, Drink, and Be Merry,” offering dining, dancing, and “colored entertainment” nightly. In the ’40s, Hopkins opened a dining club in Las Vegas, The Desert Wind, which his grandson Wilbur Tate insists was the first Vegas establishment to offer integrated dining.

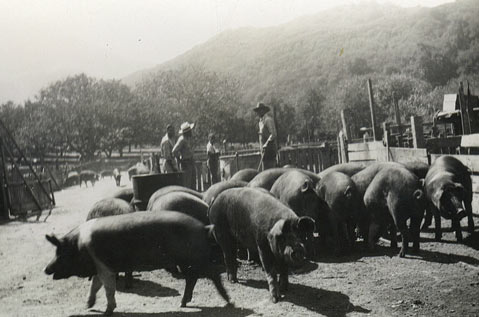

What sustained Hopkins’s far-flung ventures in the hospitality trade was a combination of trash, land, and hogs. He started a trash company, Clean Way Garbage, which collected garbage in Montecito. In 1958, Hopkins would sell his company to Mario and Charles Borgatello, whose trash company evolved to become today’s MarBorg. Before that, however, Hopkins took the trash he collected to a 400-acre ranch he owned just off Casitas Pass Road. This landholding qualified Hopkins as one of the biggest—if not the biggest—African-American property holder in Southern California. At the Casitas ranch, the trash was steam-sterilized and fed to the hogs, which Hopkins raised by the thousands. Once fattened with Montecito trash, they were trucked to the Los Angeles slaughter houses operated by Oscar Mayer and Farmer John. In addition, Hopkins owned a family home on Elizabeth Street, located half a block from the Pennywise Market on Santa Barbara’s Eastside. And for decades, he owned a rooming house where Anacapa Street now meets the freeway, one of only two places where African-American travelers and tourists could secure accommodations in Santa Barbara.

Most of what’s known about Hopkins comes courtesy of his grandson, Wilbur Tate, now an administrator at Cal State Fullerton. Although Tate grew up in Pasadena, he spent summers throughout much of the 1960s in Santa Barbara with his grandparents. In the mid ’70s, Tate attended UCSB, where he was a stand-out player on the basketball team alongside such luminaries as Don Ford. Although Tate lived in Goleta back then, he helped care for his grandfather, then in failing health.

According to Tate, his grandfather was born in Texas outside of San Antonio. Hopkins’ own father had been a slave until the age of 15; the family—two boys and a girl—grew up in a one-room tar paper shack no bigger than a backyard tool shed. As a young man, Hopkins played Negro League baseball, pitching for the San Antonio Longhorns. He boxed some, too. Depending on who you believe, Hopkins stood 6’3” at 220 pounds or 6’6” at 250 pounds—in any case, he was big and powerful. Even into his seventies, Hopkins—who loved boxer Jack Johnson but termed Muhammad Ali was a “damn big mouth”—packed a serious punch. Tate recalled watching his grandfather punch a man who’d been on his property without permission. “He hit him in the chest and, when he did, we could all feel the punch,” Tate said. “Nobody ran that ranch but Otto Hopkins.”

What propelled Hopkins from Texas to California remains the subject of speculation. He stopped first in Los Angeles, where for two years he lived in a boarding house run by the mother of Tom Bradley, Los Angeles’ first and only African-American mayor to date. That house proved the incubating ground for many successful African-American entrepreneurs and professions: attorney Johnny Cochrane’s father lived there for a while, and so, too, did noted African-American architect Paul Williams, who would later design the LAX airport, and John Hill, who would open L.A.’s first African American-owned funeral parlor and later its first African American-owned radio station. That’s also where Hopkins met Earl Grant, who would later open L.A.’s first African American-owned bank.

Grant and Hopkins would remain lifelong friends. Tate recalls Grant visiting his grandfather once a month. When Tate’s mother divorced, it was Grant who suggested that she and her two kids could move in next door in Pasadena. How much Grant invested in Hopkins’s ventures througout the years is unknown. But Grant, who had invested in hog farming himself, clearly pushed Hopkins in that direction.

Hopkins first moved to Santa Barbara with his wife, Emma, in the early 1920s. He worked briefly as a stone worker on the Californian Hotel, then just going up. According to family lore, he was fired from one job because he drove a nicer car than his boss. By 1924, according to Tate, The Cotton Club was open for business. At that point, Prohibition was still in effect. Until repeal in 1933, it would have been a speakeasy. It was big enough for smaller combos and nine-piece bands. “Blacks and whites intermingled. They had a ball,” Tate said. “It was like the last day on earth.”

How Hopkins stayed open remains a mystery. Hopkins told his grandson it would have stayed open if he’d enjoyed support from St. Paul’s Church, the African-American church located just across Haley Street from the club. Little wonder, then, that Hopkins and his wife were founding members of the Second Baptist Church on Mason Street.

According to Tate, Hopkins successfully cultivated good relations with Santa Barbara Sheriff John Ross. The sheriff, Tate said, was a regular visitor at the Hopkins ranch, where he’d bag two or three deer at a time. Tate found a concealed weapons permit issued to his grandfather by Sheriff Ross in 1946 for “protection of money while purchasing live stock.” Almost 20 years before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1964, Tate exclaimed, his grandfather was given a permit to carry a concealed .38 caliber Smith and Wesson handgun. Later, Tate said, the sheriff would give his grandfather a pearl handled revolver as a gift.

Guns would feature prominently as part of the mythic furniture surrounding his grandfather that Tate would remember. Tate recalled as a 10-year-old going to Brown’s barbershop on Haley Street and his grandfather instructing him to get the .38 out of the car and give it to him in the barber’s chair. By that time, Hopkins was getting on in years. He’d made a lot of friends, but many in Santa Barbara’s African-American community were jealous of him, as well. Hopkins remained a registered Republican even as the Civil Rights movement was taking off. “Lincoln was a Republican,” Tate recalled his grandfather saying. “George Wallace [an ardent segregationist] was a Democrat.” While Hopkins gave quietly to more moderate groups like the NAACP and the George Washington Carver Club, he had no interest in the protest movement or demonstrations then shaking America. “Boy,” he’d tell his grandson, “that’s bad for business.”

Hopkins dealt with racism, said Tate, by dressing professionally, being better prepared than his Caucasian counterparts, and smoothing over rough-edges with cases of Johnnie Walker Red strategically given to people who might impede his path. But if he was too rough, tough, and proud to acknowledge the slings and arrows of racism, his two daughters—Margaret and Earline—were not so inoculated.

Earline Tate—Wilbur’s mother—was given a name that sent her into the world with high expectations and no excuses: Artie Earline Frederick Douglas Hopkins. Being both African-American and wealthy, she fit in nowhere, really. Tall at 5’11” and beautiful and always impeccably dressed, Earline could not hide, though she tried to do just that in her studies. Earline graduated from high school in just two years, but when she walked down the aisle on graduation day 1942, no one was there to walk next to her. None of her white friends were allowed by their parents to accompany her. Earline Tate would attend USC, where African-American students were then barred from the dormitories. Still, she was the first African-American ever elected vice president of the Graduate Students Association at the School of Social Work, a distinction that in 1945 warranted a news article in the Los Angeles Times. In 1949, she would marry a light-skinned African-American man named Wilbur Tate. Oxnard police, thinking her husband was white, pulled Tate over and warned him against driving around with African-American women. Earline Tate would earn a degree in psychiatric social work and spend 31 years with the California Department of Mental Health. In 1967, she would run for Pasadena School Board, and while she didn’t win, she was the first African American ever to vie for that post.

The younger Wilbur Tate would go on to enjoy a short-lived career playing professional basketball in Europe until his knees, he said, “exploded.” In the 1980s, he worked for Democrat Willie Brown, then Speaker of California’s Assembly and widely regarded as one of the smartest men in state politics. As term limits forced Brown—then one of the most politically powerful African Americans in the United States—from office, Tate landed on his feet with an administrative position at Cal State Fullerton. His sister, Lenore, earned a PhD in geriatric psychology, now works as a clinical psychologist in Sacramento, and has two published books to her name.

Otto Hopkins—the name “Otto” reflecting the Germanic influences from Hopkins’s mother’s side of the family—died of asthma and Alzheimer’s in 1976 at the age of 79. What brought him to Santa Barbara in the first place? The same thing, said Tate, that draws everybody else: “He said it was the prettiest place he’d ever seen.”