Surfer, Robber, Writer, Lifer

Getting to Know Ben Greenspon, Santa Barbara's Bank-Robbing Son

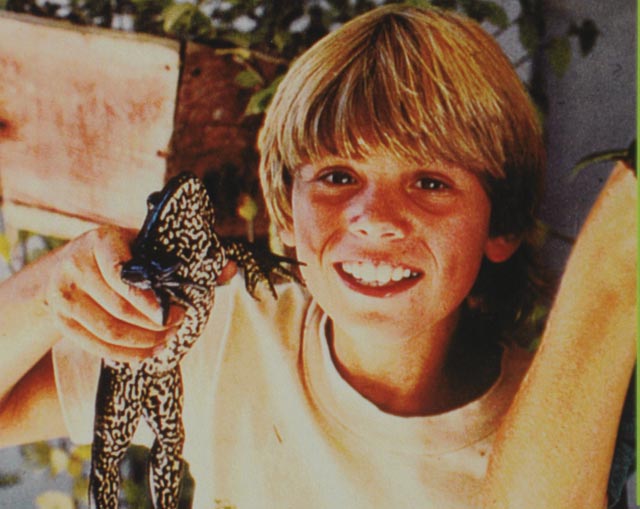

I still can’t say exactly what it was about Ben Greenspon’s story that drew me in. Part of it was the almost incomprehensible disconnection between his life sentence in prison and his ordinary boyhood — one that sounds not unlike my own early years in Santa Barbara.

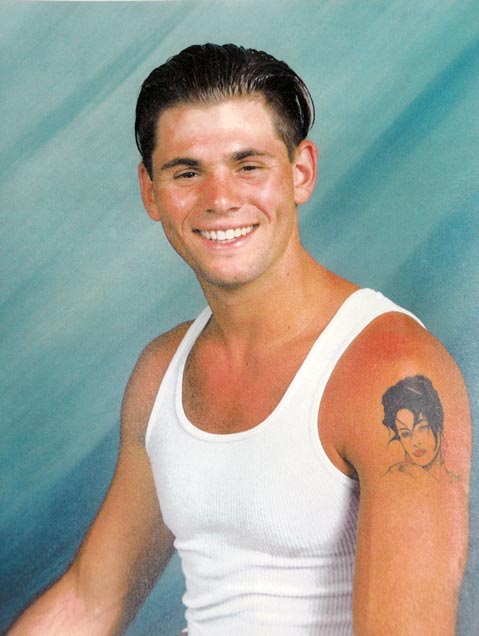

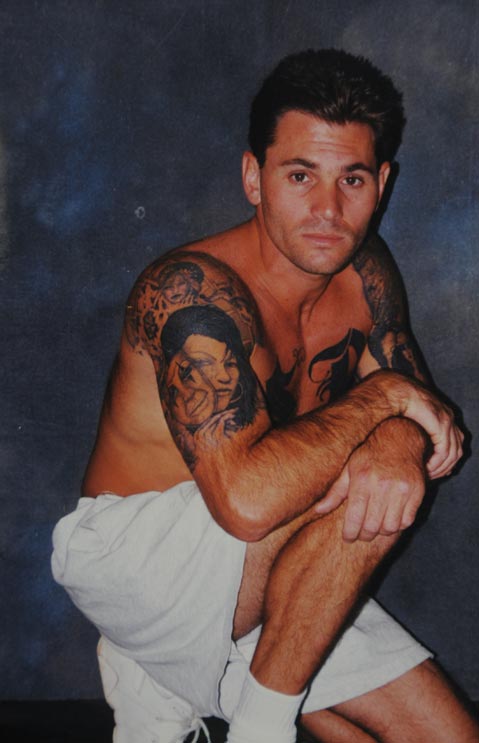

Ben was born in 1972. He was a typical Southern California kid — an adventurous, energetic boy who grew up running wild on a beautiful property off San Marcos Pass owned by his loving mother and stepfather. He went to Mountain View School, La Colina, and San Marcos High. He was a good student and a talented competitive surfer. Those who knew him in his childhood and teen years remember him as charmed, charismatic: the kind of guy who attracted people — and luck — without seeming to try.

He also had a habit of breaking the rules: At eight, he was stealing candy bars; at 12, he would wait for his dad to go to work, then load the car with surfboards and drive to the beach. In high school, he was popular, partying with the Montecito crowd. He started stealing VCRs from his friends’ parents and pawning them for extra cash, then forging checks. He was in and out of juvenile detention centers, but the experience of incarceration didn’t seem to deter him.

November 12, 2008

As a boy I ran away every day. I never went far, and I always came back happier, free. It wasn’t until I was a man that I lost my way, and ran away for real.

Before long, he was robbing banks and treating his friends to lavish gifts: sports cars, designer suits, weekend gambling sprees. In 1994, at age 21, Ben was arrested for bank robbery and sentenced to seven years in federal prison. In 2000, he was released on parole, and reunited with his family. He was stunned to be free again; his mother remembers him standing in shock in a supermarket, paralyzed by so many choices of what to eat for dinner. Yet within weeks, Ben borrowed his mother’s car, walked into a bank in San Luis Obispo unarmed, and walked out with a bag full of cash.

This time, his spree of robberies lasted less than two months. On April 25, 2000, a high-speed chase culminated in Ben struggling with a female police officer. He has always maintained that he was trying to get her to shoot him — he says he knew his luck was over, and he didn’t want to live beyond that day.

But live he did. He faced 11 felony counts, including attempted murder of a peace officer — a charge that was eventually dropped. Yet between his prior convictions and his latest slew of crimes, he was sentenced to 132 years to life in prison under California’s three-strikes law.

January 5, 2009

I ran and ran, and never considered that I was a traitor to my loved ones. Now I live with the guilt, and when my mom’s eyes tear up during a visit I see a galaxy of burnt bridges.

I first heard about Ben’s story in 2008, when I was working as an arts editor for The Independent. At a story-idea meeting one afternoon, I mentioned my interest in prison art. “That’s funny,” said one of my colleagues. “My girlfriend’s brother is in prison for life, and he’s helping other inmates get their art to the public.”

I wrote my first letter to Ben that week, and he wrote back. As our correspondence continued, I realized that what I had thought of as an interesting visual art story was something else entirely. Yes, Ben was encouraging fellow prisoners to draw and paint, but the real story here was about one man’s determination to live a meaningful life, even if it was a life behind bars. This time, I wasn’t dealing with a play or a novel or a film. It wasn’t a metaphor — something I remembered with a new shock every time I opened another of Ben’s letters. I was corresponding with a man who had broken the social contract so many times, and so flagrantly, that society had banished him.

March 22, 2009

I’m full of things to say but have no one to say them to. I’m sure of who I am now — who I would be — but nobody knows that, and that’s where the trail fades off into the woods.

And yet, amid the tragedy, disappointment, and waste, I discovered hope in the form of Ben’s creative impulse. Faced with a life in prison, he had begun not only to encourage others in their artistic pursuits but also to write — and to write prolifically. He wrote letters, essays, short stories, and novels. He asked fellow prisoners to create drawings based on his writing. He turned down recreational time in order to write. I was being let in on one man’s struggle to find his voice, even when his freedom was lost forever.

June 2, 2009

I have more regrets every year, and my once grand ego is a wilted, common daffodil … I’m a fool, a selfish fool … but hope is a thing that both floats and sinks. I’m still floating.

It’s been six months now since Ben and I stopped corresponding, but his letters still haunt me. It isn’t their literary merit that makes them so unforgettable; it’s that they represent a voice society has all but silenced. It’s a voice thick with guilt, frustration, and sorrow, but against all odds, it’s also a voice of hope.

In writing this story, it isn’t my intention to report the facts of Ben Greenspon’s case; that’s already been done. Nor is it my aim to make sense of his crimes, or to offer any kind of resolution. My intent is simply to bear witness to a Santa Barbara boy who isn’t coming home — Ben Greenspon: surfer, robber, writer, lifer.

Meeting Ben: Face-to-Face with a Bank Robber

The first thing I noticed were the shoes: thick, white rubber soles and black canvas uppers — a kind of off-brand, low-top Converse that made the men look like oversized boys.

I caught his eye when he entered the room, dressed like the rest of them in a blue chambray shirt and darker blue pants with yellow stitching. He grinned and seemed to bounce across the linoleum floor, glancing at the guard beside him, then at me, and then away again. And then, given his orders, he walked to my table, Table 9, where a pile of paper napkins lay beside two sporks in their plastic wrappers. We shook hands and grinned at each other, and I saw the thin, sharp creases at the outside corners of his eyes, the way his stubble and his short hair were flecked with white.

“So,” he said, sitting down across from me with his knees apart, placing both hands palm down on the table as if it were a regulation he followed instinctively. “How was the drive?” Beneath the table, his knees took up an insistent bouncing.

He was the same good-looking man I’d seen in all the photographs — the ones in the newspaper when he was first sentenced, and the more recent ones his mother had shown me, snapshots taken on prison visits, in front of a wall mural depicting a rain forest with giant, fakey leaves and an implausible waterfall. He was shorter than I’d imagined. When he smiled, dimples puckered his handsome face, making him look closer to 17 than 37.

I told him about the sunrise swell at Rincon, the smell of the cows on I-5, and the wrong turn that had cost me an extra 20 minutes of backtracking down a little highway through a place called Pumpkin Corner. I didn’t tell him how they’d turned me away at the security check at first because my pants were “too form-fitting in the rear,” how I’d returned to my car, changed into the second pair I’d brought, and finally walked through the metal detector and into the steel cage topped with razor wire, feeling conscious of my ass moving beneath the thin, black fabric. Good thing I’d read the visitor’s guidelines carefully and brought backups: a few changes of clothes, a pack of notepads with no spiral binding, and a quiver of pencils, their points stubbed to rounded tips.

What am I doing here? I had asked myself as I walked with the other visitors — mostly young women, some with infants in their arms — past the cell blocks to Visiting Room B. I knew the easy answer: I was a journalist pursuing a story, the story of a hometown boy who lost control and landed himself a life sentence. But beneath that answer was something deeper, some fascination I did not want to admit to myself.

Nobody had handed me this assignment. I was the one who’d reached out to Ben, encouraging him to write to me. What was it that had made my heart race every time I saw his blocky script on an envelope in the newsroom mailbox: Pleasant Valley State Prison, B. Greenspon, T-12702, D2-214? I had written back — dozens of letters over the course of nearly a year — and I had agreed to make the six-hour drive to visit him, still not knowing what the story really was, or even if there was one. Early that morning, before setting out, I had applied eyeliner and mascara. At the gas station in Coalinga, I’d bought spearmint gum to cover up the smell of coffee on my breath.

Now, sitting four feet from him, I felt my body flush with adrenaline, felt that heady mix of excitement and fear that enlivens me on a first date but also when I stand on the mat at the martial arts dojo and prepare to demonstrate my response to a simulated knife attack. I’m a black belt, I told myself now, though sitting here surrounded by men facing serious sentences for serious crimes, it felt like weak defense. From across the table, Ben winked. How had I imagined that a blunt No. 2 and a yellow legal pad could shield me from this man?

I had brought $25 in quarters — no bills, as instructed — and I offered to buy him lunch from the vending machines in the visiting room. He led me to one, and chose a slice of pepperoni pizza, a can of Sprite, and beef taquitos. I found a bean-and-cheese burrito, and dropping my quarters in one by one, looked over to see him peering into the microwave where his food was heating. He’s 37 years old, I thought, and he’ll never go to the supermarket to buy groceries, never slice a fresh tomato with a sharp knife, or grind his own coffee in the morning.

What do you talk about with a man who has been sentenced to live his life in prison, and to die there? I listened as he described his teenage years in Santa Barbara: surfing dawn patrol at Hammonds, acid trips at the Farmers Market, lounging poolside at the Coral Casino with gorgeous girls who drove Jags and Bimmers and stole cocaine from their parents. I listened to his story about attempting to escape from a temporary detention center in Washington state, looked when he pointed out the scars on his hands from trying to punch through two panes of shattered glass. “I was so close to freedom,” he said. “I couldn’t not try for it.”

“I never saw it as an act of desperation,” he explained. “It was my career.”

He told me how good he had been at robbing banks. “I never saw it as an act of desperation,” he explained. “It was my career.” And he described the ways he had spent the money: renting out strip clubs in Tucson, hitting Las Vegas with three beautiful women and a backpack full of cash.

In the next breath, he lamented his stupidity, insisting that all that mattered to him now was his family and his writing; he wanted to publish a novel and a collection of short stories and to write a screenplay, and could I help him? Part of me wanted to say yes, but I mumbled something noncommittal. He’d already sent me many of his stories — tales of Indian chiefs and talking birds, magic sea turtles and forbidden love and dark, unresolved vendettas.

I thought of all those women I had read about and disdained — the ones who fell in love with inmates on death row, desperate women drawn in by the magnetic field surrounding danger and death, by bad-boy allure, the sex appeal of crime, or the misplaced desire to fix something broken. How far was I from them now, sitting here gazing into an inmate’s eyes and wishing I could smooth his brow, give him hope, give him some kind of future?

“I haven’t had a visitor since February,” he told me, and I pictured his mother, the way she’d rolled her eyes again and again during our interview so as to keep from crying. “Do you know how long I’ve been in places like this?” Ben asked me. “Sixteen years. Almost two decades.”

I offered him more food. He chose Buffalo wings, a slice of chocolate-chip cheesecake, a pint of ice cream. At the table next to us, a young mother rearranged the baby under her arm, jiggling it to keep it quiet. The inmate beside her — the father, I thought — stared past her, his jaw clenched, his face unreadable. Ben shifted in his plastic chair. “Do you ever think about fatherhood — being a dad?” I asked him. “Nawww,” he said. “I mean, I try not to think too much about the future, you know? I don’t have much of one.” He looked at his hands, brown hands flecked with little white scars, the flat fingernails short and clean.

“It kills my mom to come here,” he said, and looked at me, and his eyes were wet and pink. “It kills her, so I don’t ask anymore. I try not to ask for anything.”

Incarcerated, Unforgettable

Ben has switched prisons twice since we began corresponding, but my questions haven’t changed: What drove him to do what he did? Was this outcome avoidable, or inevitable? Should his community take any responsibility? What might Ben do with another chance? Is forgiveness even an option? What would it look like?

Though I’ve spent months turning these questions over, I haven’t reached any answers. What I’ve gained in pursuing this story isn’t a solution; it’s simply the ability to see Ben as a human being. Through our correspondence, I’ve allowed myself to relate to him as something other than a bank robber: as a fellow Santa Barbara native, a fellow lover of nature and adventure, a fellow writer. And by meeting him in person, I have negated the possibility of ever forgetting Ben Greenspon.

In the end, Ben and I have agreed on this: Writing is the most powerful way we have found to tell our truths and unburden our hearts. The very act of writing down our stories gives us courage, even when, as Ben puts it, the trail fades off into the woods.

A Child of the Sea

I thought it was important to give Ben a chance to tell his story in his own words. I could have chosen from scores of his letters or stories, but I thought this essay captured his writing style, his love of his home and family, and how he sees his life today. I’ve edited it slightly. — ES

As a child of the sea, I’ve never seen a wave that wasn’t beautiful. As a boy I ran away every day. I never went far, and I always came back happier, free. It wasn’t until I was a man that I lost my way, and ran away for real. Even now, as a much older man, I look back and try to see past the corners of my life.

Memory is a vague comfort, sort of like a friendly stranger. My grief for the lost pieces can hide in the shadows of my tiny cell. I’ve learned to pretend there’s only a little space between our worlds. But in my world there are no waves, and no place to rest my surfboard. I hold onto a fading book of memories. I’m sure one day they’ll all be gone. When that day comes I’ll return to the ocean, somehow. Until then I’ve given myself the space I need, though judgment and regret lurk always.

If I could stand at the edge of the cliff that overlooks Jalama and feel the salty breeze, I’d remember my childhood and the life I’ve left behind. As a child I never realized the day would come when I’d wish I could go back and do it over again. As children how many of us can imagine our fate? Time and waves are alike in so many ways … when the last wave crashes, time will stop for me. I just pray that in the next journey I’ll have wisdom, and the judgment of the man I am today. I wonder where all my childhood friends are now. Some are dead, but I’m sure we’ll surf together again. I’ve seen the edge of my life, and I’ve stepped back, trying to be closer to the child I was, rather than the man I became.

I always seemed to find myself at the beach. I could be the center of a massive manhunt and forget all of it, everything. One of the most powerful memories in my life is being on a balcony in Mazatlan, looking out at the ocean, knowing my life was about to change in a way that would never be undone. Sometimes you just know … and I knew. The waves were perfect; they crashed gracefully and lulled my worst fears. I was with a woman I loved, and I wanted to tell her. I tried to let her know that one day I’d be gone, but she only heard my voice, not my words. Being together was enough to cover up truths.

I’ve been tossed around for close to two decades since that day on the balcony, and the woman I loved has lived a good life, without me. If she were to ask me why, or how, or am I sorry, I’d be speechless. I’d probably cry like a child. As a man I’m not supposed to let salty tears flow, yet I’m a far cry from the ocean’s comfort. I doubt anything I’ve ever said was heard. My life has been full of secrets and deceit. The help I’ve given the people in my life was false; the joy I had was gone before the sun set.

I often sort myself into two piles: the good and the bad. It seems like the bad pile is way bigger, but my heart wishes it weren’t so. I really did care. Whoever I helped I cared for, a lot. Can you forgive me? As a child, forgiveness was easy, and so fulfilling. As a child I’d forgive anything, and the waves would always be part of me, begging me to forgive. — Ben Greenspon, 2009