What Five Days and 30 Miles in Santa Barbara’s Backcountry Teaches You

Hiking Los Padres's Gene Marshall-Piedra Blanca National Recreation Trail

All Coyote Dave told me was that the pictographs were in a cave that looked like a Hershey’s Kiss, so I meandered on a barely noticeable path, over a gurgling stream that flows into Piru Creek, and toward a boulder field, lumpy like the chocolate candy, the telltale red shading of Chumash rock art visible upon approach. I carefully set down my backpack, sat myself down in the cool shade, and stared at the faded images, those odd creatures and celestial symbols now quite familiar to my eyes, having sought out dozens of them since my college days more than a decade ago. These weren’t in great shape, although the only evidence of actual vandalism was itself historic: a chiseled-in “H.Y.T.” in old-style serif lettering, likely the initials of a horse-riding explorer or backwoods homesteader from more than a century ago.

This is just one of the countless daily discoveries that a trek through any part of Los Padres National Forest is bound to deliver, but I experienced more than ever before on my recent, five-day, nearly 30-mile slog from Camp Scheideck to Piedra Blanca — with a two-night spur up to Fishbowls — through the Sespe Wilderness along the Gene Marshall–Piedra Blanca National Recreation Trail.

As one of the 11 travelers on my good friends’ eighth annual “Death March” this past Memorial Day weekend, we chalked up sky-high incense cedars and Jeffrey pines, eight-inch steelhead trout, bear skeletons, cougar heebie-jeebies, bracingly cold swimming holes, a brief snow storm, delicate mariposa lilies, deep-purple chia sage buds, blooming Matilija poppies, bright green moss that fell from the trees like psychedelic feathers, and a curious, phallus-like plant that erupted through the moist, needle-covered earth to show off its brilliantly red explosion of flower clusters to the world. (We later learned it was snow plant, which, perhaps even trippier, lives in a mutually beneficial relationship with the underground fungi that survive on the roots of pine trees.) There were also more paintings, including one of the most interesting designs I’d ever seen, an anthropomorphic winged beast we wound up calling the “Bird Man.”

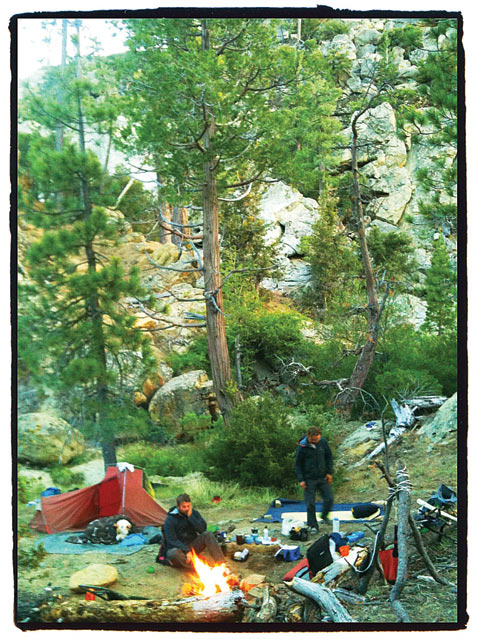

In conversations around the campfire each night, we discovered things about being human, too: that we’re made to walk, which is why day one sucks, but you feel like walking forever on day five; that maybe we snore to keep away bears, lions, and other predators at night, a theory desperately requiring research; that seafood stew, grilled tri-tip, and veggie stir fry taste much better when you’ve hauled it on your back up and down mountains for miles; that backpacking seems to be back in style, as witnessed by the 50 or so people who crammed into Fishbowls camp on Saturday night; and that if there was such a thing on the planet as powdered alcohol, we would all no doubt know about it.

But discovery is only half the game — a long backpacking trip delivers a rather refreshing sense of accomplishment, as well, and not just because you feel rather manly after trudging through the potential dangers of the wilderness with only what’s on your back to sustain you. On our last night, the available camps were so packed that we had to go a ways off trail and build our own camp. As Coyote Dave went off to get our waiting friends, he suggested I build a fire pit. I took to the job with a sense of responsibility, quickly clearing a nice piece of ground, gathering large rocks, collecting wood. Upon their return, they were impressed. “Dude, nice work,” said Coyote Dave. “You get a merit badge.”

I couldn’t hold back a smile upon getting my first badge, but it wasn’t a first for our team. One enterprising fellow tallied three on day one alone, and then we lost count: for fashioning a yucca stalk into a cane, for harvesting pine sap and cooking it into a glossy red glue, for making more yucca and an acorn cap into a smoking pipe, for deftly suggesting that bacon be wrapped around green onions and then thrown on the fire. He also patiently helped set up a deadfall trap designed to snag a rabbit or whatever might like a nibble of cheese, and while that never worked, it did deliver a name for the low-impact development that arose around my fire pit: Deadfall Camp, an ode to the trap, but also to the fallen trees and the huge rock face overlooking us that would certainly make any fall fatal.

Even though it gets mighty chilly at night — cold enough, in fact, to leave shards of ice in your water bottles — you find yourself approaching inner peace as you tighten your sleeping sack around your face, leaving just enough room to peer out toward the starry night skies. It’s the last thing you’ll see before drifting off to a deserved sleep, and it’s the same scene that the Chumash were painting on caves millennia ago. There’s magic up there, and with a good walk in the woods, you find it gently raining into your own life, even when you begrudgingly return to what we call civilization.